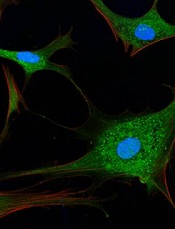

Credit: Sarah Pfau

SAN DIEGO—New research suggests that autophagy may allow cancer cells to recover and divide, rather than die, when faced with chemotherapy.

“What we showed is that if this mechanism doesn’t work right—for example, if autophagy is too high or if the target regulated by autophagy isn’t around—cancer cells may be able to rescue themselves from death caused by chemotherapies,” said study author Andrew Thorburn, PhD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

He and his colleagues believe this finding has important implications. It demonstrates a mechanism whereby autophagy controls cell death, and it further reinforces the clinical potential of inhibiting autophagy to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Dr Thorburn and his colleagues recounted their research in Cell Reports and presented it in an education session at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

The researchers had set out to examine how autophagy affects canonical death receptor-induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and apoptosis. They found that MOMP occurs at variable times in cells, and it’s delayed by autophagy.

Furthermore, autophagy leads to inefficient MOMP. This causes some cells to die via a slower process than typical apoptosis, which allows them to eventually recover and divide.

Specifically, the researchers found that, as a cancer cell begins to die, mitochondrial cell walls break down. And the cell’s mitochondria release proteins via MOMP.

But then, high autophagy allows the cell to encapsulate and “digest” these released proteins before MOMP can keep the cell well and truly dead. The cell recovers and goes on to divide.

“The implication here is that if you inhibit autophagy, you’d make this less likely to happen; ie, when you kill cancer cells, they would stay dead,” Dr Thorburn said.

He and his colleagues also found that autophagy depends on the target PUMA to regulate cell death. When PUMA is absent, it doesn’t matter if autophagy is inhibited. Without the communicating action of PUMA, cancer cells evade apoptosis and continue to survive.

The researchers said this suggests autophagy can control apoptosis via a regulator that makes MOMP faster and more efficient, thus ensuring the rapid completion of apoptosis.

“Autophagy is complex and, as yet, not fully understood,” Dr Thorburn said. “But now that we see a molecular mechanism whereby cell fate can be determined by autophagy, we hope to discover patient populations that could benefit from drugs that inhibit this action.”