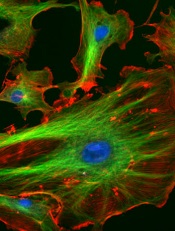

Credit: NIH

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that endothelial cells produce proteins that nurture lymphoma, thereby turning a slow-growing malignancy into an aggressive, treatment-resistant disease.

Their findings, published in Cancer Cell, challenge previous theories about cancer growth and development.

The research suggests it is not simply the number of genetic mutations in cancer cells that determines the aggressiveness of the disease.

Rather, lethality occurs when the cancer hijacks the reparative function of blood vessels, a step that ensures tumor cells’ ability to spread and resist treatment.

The researchers also found the crucial nurturing molecules that cancer co-opts from tumor blood vessels to promote invasiveness and resistance to chemotherapy. Experiments in mice showed that shutting down these previously unrecognized biological signals makes lymphoma less aggressive and improves survival.

“The endothelial cells that line the vessels orchestrate a wide variety of biological processes, good and bad,” said study author Shahin Rafii, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

“The understanding and control of blood vessel function and how this changes the malignant behaviors of cancer cells is a transformative concept and will pave the way for designing innovative treatments that disrupt signals from the local environment housing the tumor cells—a strategy that has been unappreciated.”

Dr Rafii and his colleagues studied human B-cell lymphoma cells in vitro and in mice. The team found that although the lymphoma cells harbor the same mutations, it is their interaction with and support from endothelial cells that dictates the fate and features of the disease.

Specifically, when slow-growing tumor cells come into contact with endothelial cells expressing the protein Jagged1 (Jag1), they become more aggressive and resistant to chemotherapy. However, when Jag1 is not available from surrounding blood vessels, the lethal features of the tumor cells are absent.

The researchers also found that when Jag1 binds to and activates the receptor Notch2 on tumor cells, the lymphoma becomes more tolerant of chemotherapy.

“We think signals from these abnormally stimulated tumor endothelial cells modulate the malignant features of lymphoma cells,” said Joseph Scandura, MD, PhD, of Weill Cornell. “This is a reversible process dictated by the location of the tumor cells rather than their genetics.”

“This is a critical finding because it suggests that targeting the endothelial cells with agents that disrupt their specific pro-tumorigenic signals can transform aggressive cancers into slow-growing cancers that are more sensitive to chemotherapy.”

The researchers found, for example, that blocking the Notch2 receptor in lymphoma cells or Jag1 on blood vessels made the lymphoma cells significantly more vulnerable to chemotherapy.

“This new approach to treatment would interfere with the nurturing proteins produced by tumor blood vessels,” said Bi-Sen Ding, PhD, of Weill Cornell. “It is different from traditional anti-angiogenic therapy that aims to eradicate all blood vessels in the tumor and prevent them from bringing oxygen and nutrients to the cancer.”

Dr Ding noted that conventional anti-angiogenic therapy can sometimes increase tumor cell aggressiveness by enhancing the expansion of tumor blood vessels.

But blocking specific proteins produced by the tumor blood vessels, such as Jag1, without altering oxygen and nutrient delivery, can circumvent this problem. And this approach could be translated to the clinical setting.

“[W]e can target tumor blood vessels by delivering biological cruise missiles loaded with inhibitory agents for specific cancer-promoting proteins,” Dr Ding said. This could halt tumor growth and increase sensitivity to chemotherapy.

The researchers also believe this study suggests that screening for anticancer drugs may be more effective if tumor cells are assayed in the context of signals derived from the subverted blood vessels.