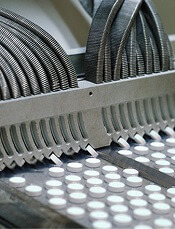

Credit: FDA

A new study suggests the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not hold drug trials to the same set of standards.

The research revealed substantial differences in trials used to support drugs approved between 2005 and 2012.

Some drugs were approved based on results from multiple studies, while other approvals were based on data from a single trial.

Furthermore, trials varied greatly with regard to size, length of study period, type of comparator, and metrics of efficacy.

These results appear in the current issue of JAMA.

“Based on our analysis, some drugs are approved on the basis of large, high-quality clinical trials, while others are approved based on results of smaller trials,” said senior study author Joseph Ross, MD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

“There was a lack of uniformity in the level of evidence the FDA used. We also found that only 40% of drug approvals involved a clinical trial that compared a new drug to existing treatment offerings. This is an important step for determining whether the new drug is a better option than existing, older drugs.”

Dr Ross and his colleagues evaluated the strength of clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval decisions by characterizing key features of efficacy trials, such as size, duration, and endpoints.

The researchers used publicly available FDA documents to identify 188 drugs approved between 2005 and 2012 for 206 indications on the basis of 448 pivotal efficacy trials.

The team identified trials for 201 of the indications. Four drugs (including 1 used for 2 different indications) were approved without a pivotal efficacy trial.

So among the 201 indications, the median number of trials reviewed per indication was 2 (interquartile range [IQR], 1-2.5). Seventy-four indications (36.8%) were approved on the basis of a single trial, 77 (38.3%) on data from 2 trials, and 50 (24.9%) on data from 3 or more trials.

Most trials were randomized (89.3%) and double-blinded (79.5%). The median duration of a trial was 14.0 weeks (IQR, 6.0-26.0 weeks), and 113 trials (25.2%) lasted 6 months or longer.

The median number of total subjects enrolled in a trial was 446 (IQR, 205-678), and the median number of patients in the intervention arm of a study was 271 (IQR, 133-426).

More than half of trials (55.1%) used a placebo for comparison, 31.9% used an active comparator (such as another drug), and 12.9% had no comparator.

The primary endpoint was a surrogate outcome in 48.9% of trials, a clinical outcome for 29%, and a clinical scale for 22.1%.

These results suggest the quality of clinical trial evidence the FDA uses to make approval decisions varies widely across indications, the researchers said.

Study author Nicholas S. Downing, a student at the Yale School of Medicine, noted that survey data suggest patients expect drugs approved by the FDA to be both safe and effective.

“Based on our study of the data, we can’t be certain that this expectation is necessarily justified,” he said, “given the quantity and quality of the variability we saw in the drug approval process.”