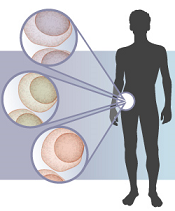

different colored cells

Credit: Lauren Solomon

Results of a new study suggest the genetic landscape of multiple myeloma (MM) may be more complex than we thought.

The research revealed “widespread” heterogeneity in samples from more than 200 MM patients.

In some cases, a single patient had multiple mutations in the same pathway. And most of the patients harbored at least 3 detectable subclonal mutations.

The researchers said these findings, published in Cancer Cell, might explain why targeted therapies are not always effective in MM and why some patients relapse after treatment.

“What this new work shows us is that when we treat an individual patient with multiple myeloma, it’s possible that we’re not just looking at one disease, but at many,” said study author Todd Golub, MD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“In the same person, there could be cancer cells with different genetic make-ups. These findings indicate a need to identify the extent of genetic diversity within a tumor as we move toward precision cancer medicine and genome-based diagnostics.”

Dr Golub and his colleagues studied samples from 203 MM patients and identified frequent mutations in genes known to play an important role in MM, including KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF.

But many of these telltale mutations were not present in all MM cells. Instead, they were often observed only in a subclonal population.

This suggests targeted therapies may have limitations in patients whose tumors are made up of these subclonal populations, the researchers said.

To explore the therapeutic implications of this research, the team performed follow-up experiments looking specifically at BRAF, a gene for which several inhibitors exist.

Previous studies indicated that roughly 4% of MM patients may have mutations in this gene. And a recent report on a single MM patient treated with drugs targeting BRAF showed promising results.

However, Dr Golub and his colleagues found evidence that treating a tumor harboring subclonal BRAF mutations with one of these agents may, at best, kill a fraction of the cells and, at worst, stimulate another cancer cell subpopulation to grow.

“There’s clearly potential for these drugs in some patients with multiple myeloma, but we show that there are also potential problems for others,” said study author Jens Lohr, MD, PhD, also of Dana-Farber.

“If a patient has a BRAF mutation in less than 100% of his cells, or if he has mutations in KRAS or NRAS at the same time, [it] may influence the response to an inhibitor.”

This suggests subclonal populations could be one of the reasons many patients suffer relapse after treatment, the researchers said.

“Matching the right drug to the right patient may not be as easy as finding a mutation and having a drug that targets it,” Dr Lohr said. “We have to keep this additional parameter of heterogeneity in mind and keep exploring what it means for therapy.”