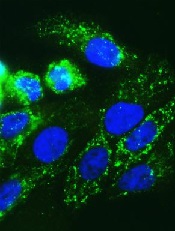

Credit: Juha Klefstrom

New research suggests the MYC protein drives cell growth by inhibiting a handful of genes involved in DNA packaging and cell death.

The study showed that MYC works through a microRNA to suppress the genes’ expression.

This marks the first time that a subset of MYC-controlled genes have been identified as critical players in the protein’s cancer-causing function, and it points to new therapeutic targets for MYC-dependent cancers.

“This is a different way of thinking about the roles of microRNA and chromatin packaging in cancer,” said Dean Felsher, MD, PhD, of the Stanford University School of Medicine in California.

“We were very surprised to learn that the overexpression of one microRNA can mimic the cancerous effect of MYC.”

Dr Felsher and his colleagues reported this discovery in Cancer Cell.

The team noted that MYC overexpression has been known to prompt an increase in the levels of a microRNA family called miR-17-92.

“People have known for several years that MYC regulates the expression of microRNAs,” Dr Felsher said. “But it wasn’t clear how this was related to MYC’s oncogenic function.”

To gain some insight, Dr Felsher and his colleagues analyzed MYC-dependent cancer cells in vitro and in vivo.

The cells in which miR-17-92 expression was locked in the “on” position kept dividing even when MYC expression was blocked. This suggested that MYC works through the microRNA family to exert its cancer-causing effects.

The researchers then looked for an overlap among genes affected by MYC overexpression and those affected by miR-17-92. There were about 401 genes whose expression was either increased or suppressed by both MYC and miR-17-92.

The team chose to focus on genes that were suppressed because these genes exhibited, on average, many more binding sites for the microRNAs. They further narrowed their panel down to 15 genes regulated by more than one miR-17-92 binding site.

Of these genes, 5 stood out. Four of them—Sin3b, Hbp1, Suv420h1, and Btg1—encode proteins known to regulate chromatin packaging.

These 4 proteins affect cell proliferation and senescence by regulating gene accessibility within the chromatin. They had never before been identified as MYC or miR-17-92 targets.

The fifth gene encodes the apoptotic protein Bim. Previous research suggested that Bim expression is affected by miR-17-92.

All 5 of the proteins are known to affect either cellular proliferation, entry into senescence, or apoptosis, in part by granting or prohibiting access to genes in tightly packaged stretches of DNA in the chromatin.

“MYC is still a general amplifier of gene transcription and expression,” Dr Felsher said. “But our study shows that the maintenance of the cancerous state relies on a more focused mechanism.”

Lastly, the researchers showed that suppressing the expression of the 5 target genes, effectively mimicking MYC overexpression, partially mitigates the effect of MYC deactivation.

Up to 30% of MYC-dependent cancer cells in culture continued to grow—compared to 11% of control cells—in the absence of MYC expression. And tumors in mice either failed to regress or recurred within a few weeks.

“One of the biggest unanswered questions in oncology is how oncogenes cause cancer, and whether you can replace an oncogene with another gene product,” Dr Felsher said.

“These experiments begin to reveal how MYC affects the self-renewal decisions of cells. They may also help us target those aspects of MYC overexpression that contribute to the cancer phenotype.”