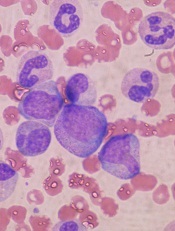

in the bone marrow

Whole-genome profiling of open chromatin is a reliable way to identify the cells of origin in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Nature Communications.

“Knowing the cell of origin of cancer cells can provide insight into tumor subtypes and possibly diagnostic and therapeutic benefit,” said study author Jennifer Trowbridge, PhD, of the Jackson Laboratory for Mammalian Genetics in Bar Harbor, Maine.

“But existing methods to identify cell of origin from bulk tumor cell samples have been unsuccessful.”

Dr Trowbridge and her colleagues hypothesized that analyzing open chromatin in bulk tumor cells might provide a better method for identifying cancer cells of origin because of the cell-type specificity of chromatin structure.

The researchers worked with a mouse model of AML driven by expression of MLL-AF9, a fusion oncogene formed by a chromosome translocation between chromosomes 9 and 11.

The team began with 5 distinct, normal cell types found in the bone marrow in both mice and humans: long-term hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), short-term HSCs, multipotent progenitors, common myeloid progenitors, and granulocyte macrophage progenitors.

The AML that developed from these different cells of origin had different penetrance and aggressiveness when engrafted in mice. The stem cell-derived lines proved the most aggressive and the committed progenitor lines the least aggressive.

These patterns were also reflected in the frequency of leukemia-initiating cells in each cell line, with HSCs having the highest frequency and committed progenitors having the lowest.

The researchers then set out to profile the open chromatin in these distinct AML samples and compare them to open chromatin patterns in normal cells using computational models.

The team identified open chromatin signatures and gene expression patterns in AML samples that may allow stem-cell-derived AML to be distinguished from progenitor-cell-of-origin AML.

These results support findings in human data suggesting the stage of a progenitor cell when it transforms to leukemia impacts clinical progression, with earlier-stage cell-of-origin cancers being more aggressive.

The researchers noted that, with further study of open chromatin in normal human stem and progenitor cell types as well as AML patient cohorts, this profiling approach could reveal precise regions with prognostic significance based on cell of origin; in other words, a valuable cancer biomarker.