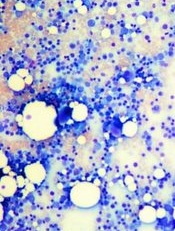

Image by Daniel E. Sabath

Modified T cells derived from patients’ bone marrow can help treat multiple myeloma (MM), according to researchers.

They modified marrow-infiltrating lymphocytes (MILs) to target MM cells and administered them to patients following chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Seven of the 22 patients treated achieved at least a 90% reduction in disease burden, which translated to an improvement in progression-free survival.

The researchers reported these results in Science Translational Medicine.

“What we learned in this small trial is that large numbers of activated MILs can selectively target and kill myeloma cells,” said Ivan Borrello, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

Dr Borrello and his colleagues set out to test the MILs in 25 patients with newly diagnosed (n=14) or relapsed (n=11) MM. The patients’ median age was 56 years (range, 30-71), 64% were male, and 82% were white.

The median number of prior treatments was 2.13 (range, 1-6). For this trial, the patients received high-dose melphalan, autologous HSCT, and MIL therapy.

Patient outcomes

Prior to HSCT, 14 patients had a partial response (PR, 64%), 3 had a very good PR (14%), 2 had a minor response (8%), and 3 had stable disease (SD, 14%). After HSCT, 7 patients were in complete response (CR, 32%), 6 had a PR (27%), 6 had SD (27%), and 3 had progressive disease (PD, 14%).

Patients received MILs when they obtained the maximal response to the last therapy. The researchers retrieved MILs from each patient’s bone marrow and expanded them with anti-CD3/CD28 beads plus interleukin-2.

Twenty-two patients received a median of 9.5×108 MILs. Three patients relapsed before they could receive the MILs.

After MIL treatment, the overall response rate was 54%. Twenty-seven percent of patients achieved a CR, 27% had a PR, 23% had SD, and 14% had PD.

Patients who achieved at least a 90% reduction in disease burden (n=7) had superior progression-free survival compared to patients who did not respond as well to treatment (n=15).

The median progression-free survival was 25.1 months and 11.8 months, respectively (P=0.01). There was no significant difference between the groups with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said none of the patients experienced serious adverse events related to the MIL therapy.

Future directions

Dr Borrello said several US cancer centers have tested similar experimental treatments, but his team is believed to be the only one testing MILs. Other types of tumor-infiltrating cells can be used, but they are usually less plentiful in patients’ tumors and may not grow as well outside the body, he said.

“Typically, immune cells from solid tumors, called tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, can be harvested and grown in only about 25% of patients who could potentially be eligible for the therapy,” said Kimberly Noonan, PhD, also of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “But in our clinical trial, we were able to harvest and grow MILs from all 22 patients.”

Dr Noonan said this small trial helped the researchers learn more about which patients may benefit from MIL therapy. For example, the team was able to determine how many of the MILs grown in the lab were specifically targeted to a patient’s tumor and whether they continued to target the tumor after being infused.

Additionally, the researchers found that patients with a high number of central memory cells before treatment had a better response to MIL therapy. Patients who began treatment with signs of an overactive immune response did not respond as well.

Dr Noonan said the team has used these data to guide 2 other ongoing trials of MILs. Those studies, she said, are trying to extend antitumor response and tumor specificity by combining the MILs with a cancer vaccine called GVAX and the drug lenalidomide, which stimulates T-cell responses.

All of the trials have also shed light on new ways to grow the MILs.

“In most of these trials, you see that the more cells you get, the better response you get in patients,” Dr Noonan said. “Learning how to improve cell growth may therefore improve the therapy.”

Researchers are also developing MILs to treat solid tumors such as lung, esophageal, and gastric cancers, as well as the pediatric cancers neuroblastoma and Ewing’s sarcoma.