Image courtesy of Blausen

Medical Communications, Inc.

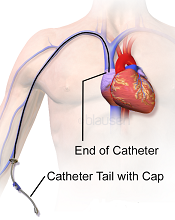

Three recently published papers may help ensure the appropriate use of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICCs).

A case-control study uncovered several factors that appear to affect the risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) associated with PICCs.

A retrospective study revealed the “prevalence, patterns, and predictors” of PICC-associated bloodstream infections.

And a literature review informed the creation of a guide to help hospitalists choose the right intravenous device.

“[PICCs] are very popular, but in an under-the-radar way, because they make care more convenient and can be placed relatively easily,” said Vineet Chopra, MD, an author on all 3 articles and a hospitalist at the University of Michigan Health System in Ann Arbor.

“But our new results, and review of research on the topic, show it’s important for physicians to think hard about both the risks and the benefits.”

Case-control study

In the study of PICC-DVT, published in Thrombosis Research, the investigators looked at records from 909 patients who received PICCs at the University of Michigan Health System in 2012 and 2013.

Patients had PICCs placed so they could receive long-term intravenous antibiotic therapy (n=447; 49.1%) or total parenteral nutrition (n=120; 6.7%). They also required PICCs for in-hospital venous access for blood draws or infusion of medications (n=342; 44.2%).

In all, 268 patients developed a DVT associated with their PICC. The median time to DVT development was 12.4 days from PICC placement.

Patients who were already taking aspirin and statins before their PICC was placed had a significantly lower risk of DVT-PICC (odds ratio [OR]=0.31). Patients who received pharmacological DVT prophylaxis had a lower risk of DVT-PICC than patients who were not on prophylaxis, although the difference was not statistically significant (OR=0.72).

Patients had a significantly greater risk of PICC-DVT if they underwent surgery during their hospital stay (OR=2.17) or had a prior history of venous thromboembolism (OR=1.70). And, compared to patients who received 4-Fr PICCs, those who had 5-Fr or 6-Fr PICCs had a significantly greater risk of DVT (ORs=2.74 and 7.40, respectively).

Retrospective study

In The American Journal of Medicine, Dr Chopra and his colleagues described a retrospective study of bloodstream infections associated with PICCs.

The investigators analyzed data from 747 patients who received 966 PICCs for a total of 26,887 catheter days. Patients had PICCs for long-term antibiotic administration (n=503; 52%), venous access (n=201; 21%), total parenteral nutrition (n=155; 16%), and chemotherapy (n=107; 11%).

There were 58 cases (6%) of PICC-bloodstream infection over 1156 catheter days, for an infection rate of 2.16 per 1000 catheter days. The median time to infection was 10 days.

Bivariate analysis revealed several factors associated with PICC-bloodstream infections. These included intensive care unit status (ICU; OR=3.23), mechanical ventilation (OR=4.39), length of stay (hospital, OR=1.04; ICU, OR=1.03), PowerPICCs (OR=2.58), devices placed by interventional radiology (OR=2.57), double lumens (OR=5.21), and triple lumens (OR=10.84).

In multivariable analysis, only some of these factors remained significantly associated with PICC-bloodstream infection. These included hospital length of stay (OR=1.04), ICU status (OR=1.02), double lumens (OR=3.99), and triple lumens (OR=6.34).

Dr Chopra said the results of these 2 studies suggest hospitalists should tread carefully when considering PICCs.

“These are not innocuous devices,” he said. “The time has come to stop thinking of them as a device of convenience and rather one with clear risks and benefits.”

Review and guide

In the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Dr Chopra and his colleagues offered advice on choosing vascular access devices. After reviewing the literature, the investigators designed a flow chart that can help hospitalists decide which device is appropriate for each patient.

For instance, different devices will work best depending on whether access to the bloodstream is needed urgently or less urgently, whether the patient will likely need the device for more or less than a week, what kind of drug or nutrition the doctor will order, and whether the patient’s kidneys are functioning normally.