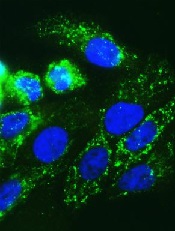

Image by Juha Klefstrom

Research has revealed a relationship between the oncogene MYC and 2 cell-surface proteins that protect cancer cells from the immune system—CD47 and PD-L1.

Researchers discovered that MYC regulates the expression of CD47 and PD-L1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) and several solid tumor malignancies.

The team said this study is the first to link 2 critical steps in cancer development—uncontrolled cell growth (courtesy of mutated or misregulated MYC) and an ability to “outsmart” the immune molecules meant to stop it (via CD47 and PD-L1).

The study was published in Science.

“Our findings describe an intimate, causal connection between how oncogenes like MYC cause cancer and how those cancer cells manage to evade the immune system,” said study author Dean Felsher, MD, PhD, of the Stanford University School of Medicine in California.

Researchers in Dr Felsher’s lab have been studying MYC for more than a decade, focusing on oncogene addiction, in which tumor cells are completely dependent on the expression of the oncogene. Blocking the expression of MYC in these cases causes the complete regression of tumors in animals.

In 2010, Dr Felsher and his colleagues showed this regression could only occur in animals with an intact immune system, but it wasn’t clear why.

“Since then, I’ve had it in the back of my mind that there must be a relationship between MYC and the immune system,” Dr Felsher said.

So he and his colleagues decided to see if there was a link between MYC expression and the levels of CD47 and PD-L1 proteins on the surface of cancer cells. They investigated what would happen if they actively turned off MYC expression in tumor cells from mice or humans.

The researchers found that a reduction in MYC caused a similar reduction in the levels of CD47 and PD-L1 proteins on the surface of mouse and human T-ALL cells, mouse and human liver cancer cells, human skin cancer cells, and human non-small-cell lung cancer cells.

In contrast, levels of other immune regulatory molecules found on the surface of the cells were unaffected.

In gene expression data on tumor samples from hundreds of patients, the researchers found that levels of MYC expression correlated strongly with expression levels of CD47 and PD-L1 genes in liver, kidney, and colorectal tumors.

The team then looked directly at the regulatory regions in the CD47 and PD-L1 genes. They found high levels of the MYC protein bound directly to the promoter regions of CD47 and PD-L1 in mouse T-ALL cells and in a human osteosarcoma cell line.

The researchers were also able to verify that this binding increased the expression of CD47 in a human B cell line.

Finally, the team engineered mouse T-ALL cells to constantly express CD47 or PD-L1 regardless of MYC expression status.

These cells were better able than control cells to evade the detection of immune cells like macrophages and T cells. And, unlike in previous experiments, tumors arising from these cells did not regress when MYC expression was deactivated.

“What we’re learning is that if CD47 and PD-L1 are present on the surfaces of cancer cells, even if you shut down a cancer gene, the animal doesn’t mount an adequate immune response, and the tumors don’t regress,” Dr Felsher said.

Therefore, this work suggests a combination of therapies targeting the expression of both MYC and CD47 or PD-L1 could possibly have a synergistic effect by slowing or stopping tumor growth and waving a red flag at the immune system.

“There is a growing sense of tremendous excitement in the field of cancer immunotherapy,” Dr Felsher said. “In many cases, it’s working, but it’s not been clear why some cancers are more sensitive than others. Our work highlights a direct link between oncogene expression and immune regulation that could be exploited to help patients.”