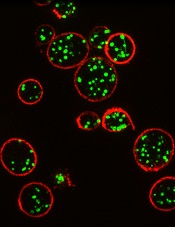

Courtesy of Dan Cutler

A proof-of-concept study suggests structured illumination microscopy (SIM) enables accurate diagnosis of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome (HPS), an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by platelet dysfunction and prolonged bleeding.

Researchers therefore believe SIM could provide a more accessible and cost-effective method for diagnosing platelet disorders.

They also said SIM provides detailed data that may enable personalized treatments.

The researchers described their results with SIM in the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis.

The team noted that electron microscopy can be used to diagnose HPS and other disorders characterized by platelet dysfunction. But the method is costly, requires fresh samples, gives limited information, and is not widely available.

“We’ve found that SIM has a lot of advantages over whole mount electron microscopy as a diagnosis method,” said study author David Westmoreland, of University College London in the UK.

“Samples don’t need to be analyzed live and can be reanalyzed, and automation means analysis is unbiased and less time-consuming. Given about 75% of patients with a bleeding disorder such as Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome are initially misdiagnosed, and 28% need to see between 4 to 6 specialists before receiving the correct diagnosis, there is a demand for a new method of analysis.”

For this proof-of-concept study, Westmoreland and his colleagues used SIM to image platelet granules in blood samples using a marker protein, CD63.

The imaging technology was custom-built by the team to automatically count the number of granules per platelet, thereby identifying patients with HPS, a rare disorder thought to affect 1 in 500,000 people.

The researchers distinguished the 3 patients with HPS from 7 normal controls with 99% confidence. Automated counting of granules showed that individuals with the disorder had a third as many granules as controls.

“Our limited analysis of this new method is extremely promising, and we hope to take it forward to test for multiple parameters with different markers,” said Dan Cutler, PhD, also of University College London.

“In this way, we could use a single super-resolution image to screen for many different platelet-based blood disorders.”