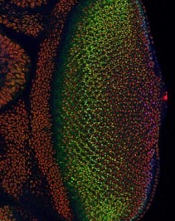

Image courtesy of

Northwestern University

In studying the fruit fly equivalent of an oncogene implicated in human leukemias, researchers have gained insight into how developing cells switch to a specialized state and how that process might go awry in cancers.

The team found that levels of the protein Yan start fluctuating wildly when a cell is switching from a stem-like state to a more specialized state. If the levels of Yan don’t or can’t fluctuate, the cell doesn’t differentiate.

The Yan protein is called Tel-1 in humans, and the gene that produces the Tel-1 protein, the Tel-1 oncogene, is frequently mutated in human leukemias.

Richard W. Carthew, PhD, of Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues conducted this research and reported the results in eLife.

The researchers studied cell behavior in the eye of Drosophila melanogaster, the common fruit fly, which has many of the same oncogenes as humans.

The team was surprised to discover that fluctuating levels of Yan were needed for cell differentiation.

“This mad fluctuation, or noise, happens at the time of cell transition,” Dr Carthew explained. “For the first time, we see there is a brief time period as the developing cell goes from point A to point B. The noise is a state of ‘in between’ and is important for cells to switch to a more specialized state. This limbo might be where normal cells take a cancerous path.”

He noted that it takes 15 to 20 hours for a fruit fly cell to transition from an unspecialized to a specialized state. The researchers found the Yan protein is “noisy,” or fluctuating, for 6 to 8 of those hours.

The team also found that a molecular signal received by the cell receptor EGFR is important for turning the noise off. If that signal is not received, the cell remains in an uncontrolled state.

The EGFR protein that turns off the noise in flies is called Her-2 in humans, and the Her-2 oncogene is known to play an important role in breast cancer.

“On the surface, flies and humans are very different, but we share a remarkable amount of infrastructure,” Dr Carthew noted. “We can use fruit fly genetics to understand how humans work and how things go wrong in cancer and other diseases.”