SAN ANTONIO – The much-publicized wide disparities in the estimated value of mammographic screening for breast cancer reported in recent major reviews are overblown and largely an artifact of methodologic differences, according to a new examination of the evidence.

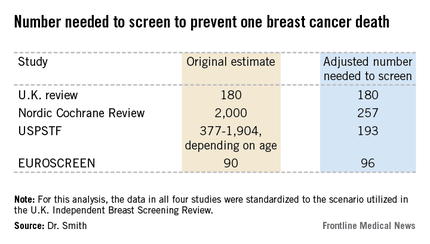

The four recent major reviews of the data regarding the absolute benefits of mammography came up with estimates ranging from 90-2,000 of the number of women who need to be screened (NNS) in order to prevent one death from breast cancer. That greater than 20-fold difference in estimated magnitude of benefit has done little to inspire public and physician confidence that mammography is a key tool in reducing cancer deaths.

But the two analyses with the least supportive outcomes – the Nordic Cochrane and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF-) analyses – used follow-up periods of 10 and 15 years, respectively. That follow-up is too short a time to assess the full value of mammographic screening, Robert A. Smith, Ph.D., asserted at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

To illustrate: In a European mammographic screening study with a 30-year follow-up, the NNS after 10 years was 922 women. By 29 years of follow-up, the NNS had fallen to 414.

"At 10 years of follow-up, you haven’t even observed half of the deaths prevented. So follow-up of 20 years at a minimum is really critical to begin to see the full benefit of screening," according to Dr. Smith, senior director of cancer screening at the American Cancer Society in Atlanta.

Also, several of the major reviews estimated the absolute mortality benefit of screening by means of an intent-to-treat analysis based upon the number of women invited to screening in randomized trials. That approach, too, is highly problematic because commonly 30%-40% of women invited to breast cancer screening in randomized trials never actually present for mammography, he said.

"The difference between the number-needed-to-invite and number-needed-to-screen is quite a critical difference in these estimates of absolute benefit. If you want to measure the effectiveness, you have to appreciate that a letter of invitation doesn’t do anyone any good. You have to show up to get mammography in order to benefit from it," Dr. Smith observed.

All of the four recent major reviews – the Nordic Cochrane (Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;6:CD001877), the USPSTF (Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:727-37), the U.K. Independent Breast Screening Review (Br. J. Cancer 2013;108:2205-40), and the European Screening Network (EUROSCREEN) Review (J. Med. Screen. 2012;19 Suppl1:14-25) – painted different pictures of the benefits of mammographic screening because they focused on different age groups, with different screening and follow-up durations, and were inconsistent as to whether the appropriate yardstick was NNS or number-needed-to-invite.

Dr. Smith and his coinvestigators sought to level the playing field by reanalyzing each review, standardizing the data to the scenario utilized in the U.K. independent review. They picked the U.K. review as the reference because it was most recently published and it was led by renowned statistical experts who aren’t part of the debate over mammography’s value. The U.K. review scenario entailed screening every 3 years for 20 years starting at age 50 years, with a 20-year follow-up period and the endpoint being breast cancer mortality at ages 55-79 years. When the data were reanalyzed in this way, the magnitude of the difference between the high and low estimates of absolute benefit among the four major reviews dropped from more than 20-fold to less than 3-fold.

"The so-called controversy over the benefit of mammography screening as estimated from the trials is largely contrived," he declared. "In short, once you standardize the evidence to the same population, the same screening scenario, and the same duration of follow-up, then the differences in absolute benefit over 20 years in the reviews become really not so significant or important at all. They are hardly worth discussing, and are certainly not enough to question the value of mammography over a lifetime of screening."

The flip side of estimating the benefit of mammographic screening in terms of breast cancer deaths avoided is the harm from overdiagnosis of cancers that never would have been symptomatic during a woman’s lifetime and wouldn’t have been detected had screening mammography not been performed. Here again, the estimates reported in the four reviews differed widely because of the divergent analytic methods employed. The U.K. review concluded that for every death from breast cancer avoided via mammography, three people would be overdiagnosed, for an overdiagnosis rate of 19%. The Nordic Cochrane analysis estimated 10 cases of overdiagnosis for every breast cancer death avoided, for a 30% overdiagnosis rate. The USPSTF didn’t give an overdiagnosis estimate. The EUROSCREEN group calculated that for every two breast cancer deaths avoided there would be one case of overdiagnosis, for a 6.5% overdiagnosis rate.