It is clear that the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic is one of the most extraordinary epochs of our professional and personal lives. Besides the challenges to the techniques and technologies of care for this illness, we are seeing challenges to the fundamentals of health care, both to the systems whereby it is delivered, and to the ethical principles that guide that delivery. There is unprecedented relevance of certain ethical issues in the practice of medicine, many of which have previously been discussed in classrooms and textbooks, but now are at play in daily practice, particularly at the frontlines of the war against COVID-19.1 In this article, I highlight several ethical dilemmas that are salient to these unique times. Some of the most compelling issues can be sorted into 2 clearly overlapping domains: triage ethics and equity ethics.

Triage ethics

In the areas most greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, scarcity of treatment resources, such as ventilators, is a legitimate concern. French surgeon Dominique Jean Larry was the first to establish medical sorting protocols in the context of the battles of the Napoleonic wars, for which he used the French word triage, meaning “sorting.”2 He articulated 3 prognostic categories: 1) those who would die even with treatment, 2) those who would live without treatment, and 3) those who would die unless treated. Triage decisions arise in the context of insufficient resources, particularly space, staff, and supplies. Although usually identified with disasters, these decisions can arise in other contexts where personnel or technological resources are inadequate. Indeed, one of the first modern incarnations of triage ethics in American civilian life was in the early days of hemodialysis, when so-called “God committees” made complex decisions about which patients would be able to use this new, rare technology.3

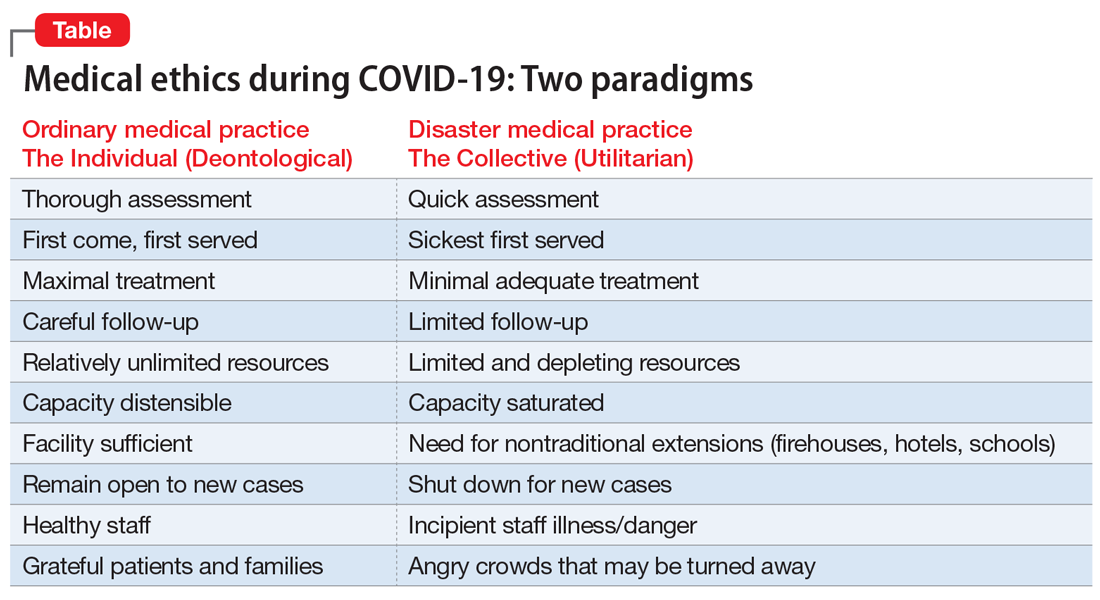

Two fundamental moral constructs undergird medical ethics: deontological and utilitarian. The former, in which most clinicians traffic in ordinary practice, is driven by principles or moral rules such as the sanctity of life, the rule of fairness, and the principle of autonomy.4 They apply primarily in the context of treating an individual patient. The utilitarian way of reasoning is not as familiar to clinicians. It is focused on the broader context, the common good, the health of the group. It asks to calculate “the greatest good for the greatest number” as a means of navigating ethical dilemmas.5 The utilitarian perspective is far more familiar to policymakers, health care administrators, and public health professionals. It tends to be anathema to clinicians. However, disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic ask some clinicians, particularly inpatient physicians, to shift from their usual deontological perspective to a utilitarian one, because triage ethics fundamentally draw on utilitarian reasoning. This can be quite anguishing to clinicians who typically work with individual patients in settings of more adequate, if not abundant, resources. What may feel wrong in a deontological mode can be seen as ethically right in a utilitarian framework.

The Table compares and contrasts these 2 paradigms and how they manifest in the clinical trenches, in a protracted health care crisis with limited resources.

The COVID-19 crisis has produced an unprecedented and extended exposure of clinicians to triage situations in the face of limited resources such as ventilators, personnel, personal protective equipment, etc.6 Numerous possible approaches to deploying limited supplies are being considered. On what basis should such decisions be made? How can fairness be optimally manifest? Some possibilities include:

- first come, first served

- youngest first

- lottery

- short-term survivability

- long-term prognosis for quality of life

- value of a patient to the lives of others (eg, parents, health care workers, vaccine researchers).

One particularly interesting exploration of these questions was done in Maryland and reported in the “Maryland Framework for the Allocation of Scarce Life-sustaining Medical Resources in a Catastrophic Public Health Emergency.”7 This was the product of a multi-year consultation, ending in 2017, with several constituencies, including clinicians, politicians, hospital administrators, and members of the public brainstorming about approaches to allocating a hypothetical scarcity of ventilators. Interestingly, there was one broad consensus among these groups: a ventilator should not be withdrawn from a patient already using it to give to a “better” candidate who comes along later.

Some institutions have developed a method of making triage decisions that takes such decisions out of the hands of individual clinicians and instead assigns them to specialized “triage teams” made up of ethicists and clinicians experienced in critical care, to develop more distance from the emotions at the bedside. To minimize bias, such teams are often insulated from getting personal information about the patient, and receive only acute clinical information.8

Continue to: The pros and cons of these approaches...