LONDON – Cancer itself has cardiotoxic effects independent of those caused by chemotherapy, Dr. Stephan von Haehling said at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Evidence from both animal and human studies indicates that the malignancy itself may be exerting adverse cardiac effects even before chemotherapy provides an additional hit to the heart, according to Dr. von Haehling, who is a cardiologist at Charity Medical School, Berlin.

“In patients with advanced cancer, significant alterations exist in several markers of cardiovascular perturbation independent of high-dose chemotherapy. So it looks like the cancer is doing something that’s further worsened when chemotherapy starts,” he explained.

Dr. von Haehling and his coinvestigators first demonstrated this phenomenon in a rat model of liver cancer (Eur Heart J. 2014 Apr;35[14]:932-41). The tumor-bearing rats had the classic symptoms of cancer cachexia, including fatigue, impaired exercise capacity, loss of body weight, and dyspnea, as well as progressive wasting of left ventricular mass, even before exposure to chemotherapy. Strikingly, administration of the cardioselective beta-blocker bisoprolol and the aldosterone inhibitor spironolactone reduced left ventricular wasting, curbed cardiac dysfunction, improved a validated measure of rat quality of life, and significantly prolonged rat survival, compared with placebo.

Further exploration of these findings in clinical trials deserves to be a priority in light of the potential quality-of-life benefits for cancer patients, Dr. von Haehling observed.

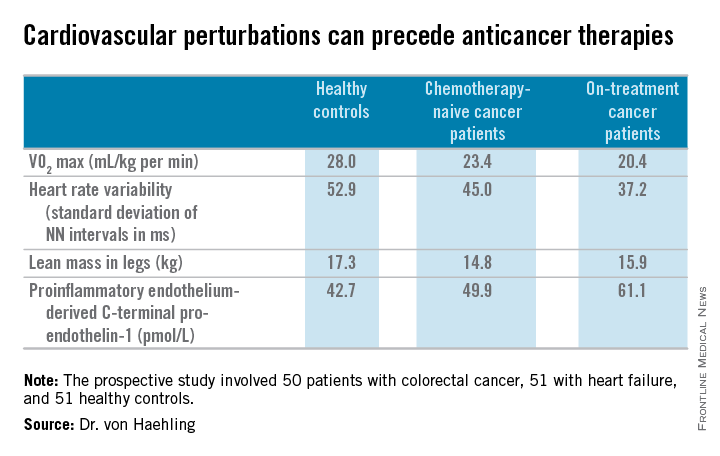

He and his coworkers followed up the rat study with a prospective study of 50 patients with colorectal cancer, 51 with heart failure, and 51 healthy controls. Of the colorectal cancer patients, 24 underwent echocardiography and other cardiovascular function studies before they went on chemotherapy, while the other 26 did so after starting chemotherapy.

The colorectal cancer patients had a mildly elevated heart rate: an average of 73 beats per minute, compared with 65 bpm in controls and in heart failure patients on beta-blocker therapy. “This is something I see quite often. These patients usually have a mildly elevated heart rate in the range of 80-90 [bpms] or even slightly above,” he said.

Heart rate variability, exercise capacity as measured by treadmill VO2 max testing, and left ventricular ejection fraction were significantly lower in cancer patients than controls, and lower still in the heart failure patients. More interesting were the differences between chemotherapy-naive and on-treatment colorectal cancer patients. Several major determinants of cardiovascular function were impaired in chemotherapy-naive cancer patients, compared with controls, and even more severely impaired in cancer patients on chemotherapy.

For more about current thinking regarding the prevention, monitoring, and treatment of cardiac side effects of anticancer therapies, Dr. von Haehling recommended the multidisciplinary clinical practice guidelines developed by the European Society for Medical Oncology (Ann Oncol. 2012 Oct;23 Suppl 7:vii155-66).

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding his cardio-oncology studies.