Sickle cell trait doesn’t raise the risk of death but does raise the risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis among black soldiers, “a population that is known to engage consistently in regular and strenuous exercise while protected by exertional-injury precautions,” investigators reported. The study was published online Aug. 4 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

A number of high-profile deaths among athletes and military personnel involving exertional rhabdomyolysis have been attributed to sickle cell trait. The National Collegiate Athletic Association, the U.S. Air Force, and the U.S. Navy all require universal screening for sickle cell trait.

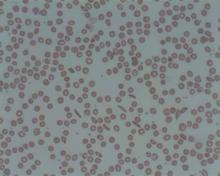

“However, concerns have been raised by the American Society of Hematology and other professional organizations about the possibility of stigmatization and discrimination resulting from the mandated screening for sickle cell trait,” which predominantly affects people of African descent and some of Hispanic ancestry, but usually not whites, wrote D. Alan Nelson, PhD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and his associates.

“These concerns warrant consideration, especially given the absence of published evidence that such screening is effective in preventing exertion-related events,” added the researchers.

The U.S. Army primarily screens for sickle cell trait among personnel deployed for combat and certain specialists whose work at high altitudes puts them at risk. To study a large enough population to generate accurate data about this rare blood abnormality, the investigators analyzed data for 47,944 black soldiers who had been tested for sickle cell trait and who served on active duty during a recent 3-year period.

The researchers assessed all inpatient and outpatient health care visits at military and civilian facilities. There were 391 exertional rhabdomyolysis events and 96 deaths from all causes during 1.61 million person-months of observation. A total of 7.4% of the study cohort carried sickle cell trait. These participants were similar to noncarriers in demographic characteristics and health predictors.

Soldiers with sickle cell trait did not have a greater risk of death than did those without sickle cell trait (hazard ratio, 0.99), and there also was no difference between carriers and noncarriers in either battle-related or non–battle-related mortality rates.

However, sickle cell trait was associated with a 54% greater risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis (HR, 1.54), Dr. Nelson and his associates noted (N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516257).

It is important to note that factors other than sickle cell trait raised the risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis to a similar or even greater degree, including obesity (HR, 1.39) and tobacco use (HR, 1.54). Recent use of antipsychotic medication tripled the risk for exertional rhabdomyolysis (HR, 3.02), and statin use nearly tripled it (HR, 2.89).

“These findings are compelling because case reports dominate the relevant literature and emphasize the presence of sickle cell trait as a risk factor for adverse outcomes, including exertional rhabdomyolysis and sudden death,” the researchers wrote. “A large longitudinal study involving a population fully tested for sickle cell trait that has formally investigated [these outcomes] while also examining other known major risk factors, such as medications, has been lacking.”

The study found that women were at much lower risk for exertional rhabdomyolysis than were men (HR, 0.51), and that risk increased with increasing age, so that soldiers aged 36 years and older had a 57% greater risk compared with those in the youngest age group.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences supported the study. Dr. Nelson and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.