A one-two combination consisting of a drug to deplete amyloid fibrils from circulation and a monoclonal antibody to mop up residual amyloid protein appears to be safe and shows promising activity against systemic amyloidosis in an early clinical trial.

Pairing the investigational small molecule agent miridesap and the experimental monoclonal antibody dezamizumab resulted in clearance or reductions in amyloid deposits in the livers, spleens, and kidneys of adults with systemic amyloidosis, reported Prof. Sir Mark B. Pepys of University College, London, and his colleagues.

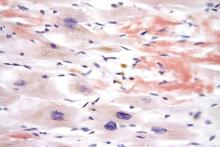

Systemic amyloidosis is caused by extracellular deposition of amyloid fibrils coated with serum amyloid P component (SAP), a normal plasma protein. Miridesap has been shown to deplete levels of circulating SAP, but fails to clear SAP lingering in amyloid deposits. Dezamizumab is a fully humanized immunoglobulin G1 antibody that is directed against SAP and provokes immune system clearance of residual protein.

The investigators enrolled 23 adults with systemic amyloidosis into an open-label, nonrandomized trial of safety, pharmacokinetics, and dose responses to up to three cycles of miridesap followed by dezamizumab. They used scintigraphy with radiolabeling to measure amyloid burden, equilibrium MRI to measure organ extracellular volume, and transient elastography to evaluate liver stiffness.

They found that a 2,000-mg dose of dezamizumab reduced amyloid load in the liver and/or spleen in five of seven patients, and that liver stiffness, a sensitive marker for hepatic amyloid load, initially increased in some patients, but then fell “substantially,” suggesting amyloid clearance and resolution of cellular infiltrates. Progressive dose-related clearance of amyloid in the liver was also associated with improvements in liver function tests.

In addition, 7 of 11 patients had reductions in renal amyloid burden, with the greatest benefit seen in patients treated with higher doses of the antibody.

The trial cohort also included six patients with clinical cardiac amyloidosis: three with monoclonal immunoglobulin light-chain amyloidosis (AL), and three with ATTR (transthyretin) amyloidosis. Although the investigators had excluded patients with cardiac amyloidosis in the first part of the study out of safety concerns, there were no new arrhythmias and no increases in cardiac troponin T or creatine kinase concentrations. One patient had a 17% reduction in left ventricular mass, suggesting a reduction in cardiac amyloid burden.

Patients tolerated the treatment, with self-limiting, early-onset rashes after higher antibody doses being the most frequent adverse event.

“However, the identified and potential risks of the intervention are considered manageable, and thus acceptable, in relation to the demonstrable clinical benefits of removing amyloid from vital organs,” the investigators wrote.

GlaxoSmithKline funded the study. Three of the coauthors are GSK employees and stockholders. Prof. Pepys is the inventor on patents for miridesap and miridesap plus anti-SAP antibody.

Source: Richards D et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aan3128.