PARIS – Adding information about response to initial therapy for thyroid cancer could improve risk stratification for patients and guide more effective long-term follow-up.

A prospective study reported Sept. 15 at the International Thyroid Congress found that among those who did not respond well to initial treatment, 50% initially classified as low risk developed persistent disease over a 5-year follow-up period. Conversely, Dr. Maria G. Castagna said, half of the initial high-risk patients remained in clinical remission throughout the study.

“This observation strongly supports the concept of ongoing risk stratification throughout the patient’s treatment and follow-up,” said Dr. Castagna of the University of Siena, Italy.

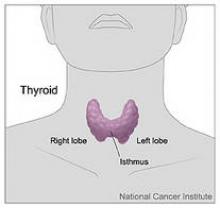

She presented data on 548 patients who were treated for differentiated thyroid cancer. All were risk stratified according to the 2006 European Thyroid Association Consensus. By this method, 284 were considered low risk (tumor 2-4 cm, no distal or nodal metastases) and 264 as high risk (tumor size larger than 4 cm, distal or nodal metastases, or tumor extension beyond the thyroid capsule).

Women made up three-fourths of the group; 90% had papillary thyroid cancer. Most (80%) underwent a total thyroidectomy, and 89% had radioiodine ablation. The average follow-up period was 5.5 years, but some had 10-year data available.

At the time of first follow-up (1 year after initial therapy), clinical remission was significantly higher in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group (85% vs. 53%), and persistent disease was significantly higher in the high-risk than the low-risk group (47% vs. 15%). “This suggests that response to initial treatment is correlated to the original risk stratification,” Dr. Castagna said.

She then evaluated the 1-year clinical outcome only in those 382 patients who were disease free at that time (140 high-risk and 242 low-risk patients). Clinical remission occurred in 98% of the low-risk group and 96% of the high risk group. “The majority of these patients in both groups continued to do well; the rate of recurrent disease was very low without difference between the groups. This suggests that patients in clinical remission after their initial treatment have a good prognosis regardless of their initial staging,” she said.

At the 5-year follow-up, most of those with a good initial response also remained well, with 96% of the low-risk group and 90% of the high-risk group being disease-free. A good prognosis continued in those available for a 10-year follow-up. Among this group, 96% of low-risk and 90% of high-risk patients remained disease free.

“We then evaluated the clinical outcomes of the 166 patients who had persistent disease at 1 year after treatment,” Dr. Castagna said. Of these, 42 had been initially classed as low risk and 124 as high risk. At an average follow-up of almost 7 years, among the low-risk patients, 52% were in remission, and 48% had persistent disease. Among the high-risk group, 52% had persistent disease, 43% were in remission, and 5% were dead from thyroid cancer. “This suggests that in this group of patients, clinical outcome was not related to the initial risk stratification.”

“Our findings suggest that when classified on the basis of response to initial therapy, 50% of patients initially classified as high risk will convert to a low-risk status, and similarly, 50% of those initially classed as low risk will convert to high risk,” she said. “While the initial risk stratification represented a good starting point for treatment, based on data available at the time, during follow-up additional clinical data are accumulated and they may increase or decrease the initial risk estimate. These data should be included so that we can more effectively guide patient follow-up.”