VALENCIA, Spain - Despite treatment, nearly half of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis continue to experience active disease and many report significant physical fatigue, according to researchers at the Congress of the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society.

“Our results point out that JIA is a controllable and treatable, but not curable, disease for a majority of the children,” coauthor Dr. Marite Rygg of St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim, Norway, said in an interview.

Her colleague, Dr. Ellen Nordal, reported 7-year follow-up data on 427 children who were enrolled in the Nordic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Cohort from 1997-2000. The cohort comprised patients from 12 centers in Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. At the congress, Dr. Nordal reported complete follow-up data on 427 of the children.

Most the patients (66%) were girls. Their median age at the onset of disease was 6 years. The most common arthritis subtype in the group was oligoarthritis; this was persistent in 126 and extended in 75. Other disease subtypes included polyarthritis (n=82); psoriatic arthritis (13); enthesitis-related arthritis (49); undifferentiated arthritis (64), and systemic arthritis (18). Uveitis developed in 89 children during the follow-up period.

At baseline, almost all of the children (97%) had taken a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. About half (48%) had taken methotrexate, while 74% had received intra-articular glucocorticoids and 32% received oral glucocorticoids. More than half (58%) had used a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug, including an anti-TNF (anti–tumor necrosis factor) drug. Only 3% were not taking any medications at baseline.

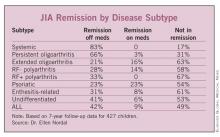

The mean follow-up period was 98 months. By that time, 42% were in remission and off medication. However, more than half of the group (58%) were either not in remission (49%) or in remission on medication (9%) said Dr. Nordal, a pediatric rheumatologist at the University Hospital of North Norway, Troms?.

Rates of remission off medication varied by subtype, with the greatest rate occurring among those with systemic arthritis (83%). The lowest rates of remission off medication occurred in those with extended oligoarthritis (21%) and psoriatic arthritis (23%).

The highest rates of ongoing disease occurred in those children who had rheumatoid factor–positive polyarthritis (67%) and extended oligoarthritis (63%). But more than half of those children with rheumatoid factor–negative polyarthritis, psoriatic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis, and undifferentiated arthritis also failed to achieve remission.

Fatigue is another aspect of the disease that continues to bother young people as they grow into their teens, according to registered nurse Deborah Hilderson of the Catholic University of Leuven, Belgium. She presented the results of a small cross-sectional study of 31 adolescents with JIA, which examined the impact of fatigue on their daily lives. The patients were compared with a group of healthy controls used in a 2003 study of excess fatigue in young adult survivors of childhood cancer (Eur. J. Cancer 2003;39:204-14).

The patients had a mean age of 16 years; all had been treated at the University Hospital Leuven in Belgium. Most of the group (23) was female. Persistent or extended oligoarthritis was present in 11 patients; rheumatoid factor-negative polyarthritis in 9; systemic arthritis in 4; and enthesitis-related arthritis in 7.

They completed two quality of life measures. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) scores fatigue on a 20-point scale in five domains: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation. High scores indicate higher fatigue levels. The 100-point Quality of Life Linear Analog Scale rates 100 as the best quality of life imaginable, and 0 the worst.

About 13% of the patients reported a score of 15 or higher in the general fatigue domain of the MFI. There were no significant differences between the disease subtypes for any of the five fatigue domains. Compared with controls, patients reported significantly higher scores for physical fatigue and reduced activity. However, Ms. Hilderson pointed out, although the differences were statistically significant, the actual differences were “rather small.”

The median quality of life score was 74, but the range was wide (10-97). Higher quality of life scores were significantly associated with lower fatigue scores. There was a moderate association between quality of life and general and mental fatigue, Ms. Hilderson said.

“Fatigue does seem to be a problem for adolescents with JIA, and we, as health care providers, do need to pay attention to this complaint, particularly in patients with active arthritis,” Ms. Hilderson said.