There are about 2 million to 4 million homebound patients in the United States, according to a webinar from The Trust for America’s Health, which was broadcast in March. But many of these individuals have not been vaccinated yet because of logistical challenges.

Some homebound COVID-19 immunization programs are administering Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to their patients, but many state, city, and local programs administered the Johnson & Johnson vaccine after it was cleared for use by the Food and Drug Administration in February 2021. The efficacy of the one-shot vaccine, as well as it being easier to store and ship than the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, makes getting it to homebound patients less challenging.

“With Pfizer and Moderna, transportation is a challenge because the temperature demands and the fragility of [messenger] RNA–based vaccines,” Brent Feorene, executive director of the American Academy of Home Care Medicine, said in an interview. That’s why [the Johnson & Johnson] vaccine held such promise – it’s less fragile, [can be stored in] higher temperatures, and was a one shot.”

Other hurdles to getting homebound patients vaccinated had already been in place prior to the 10-day-pause on using the J&J vaccine that occurred for federal agencies to consider possible serious side effects linked to it.

Many roadblocks to vaccination

Although many homebound patients can’t readily go out into the community and be exposed to the COVID-19 virus themselves, they are dependent on caregivers and family members who do go out into the community.

“Their friends, family, neighbors, home health aides, and other kinds of health care workers come into the home,” said Shawn Amer, clinical program director at Central Ohio Primary Care in Columbus.

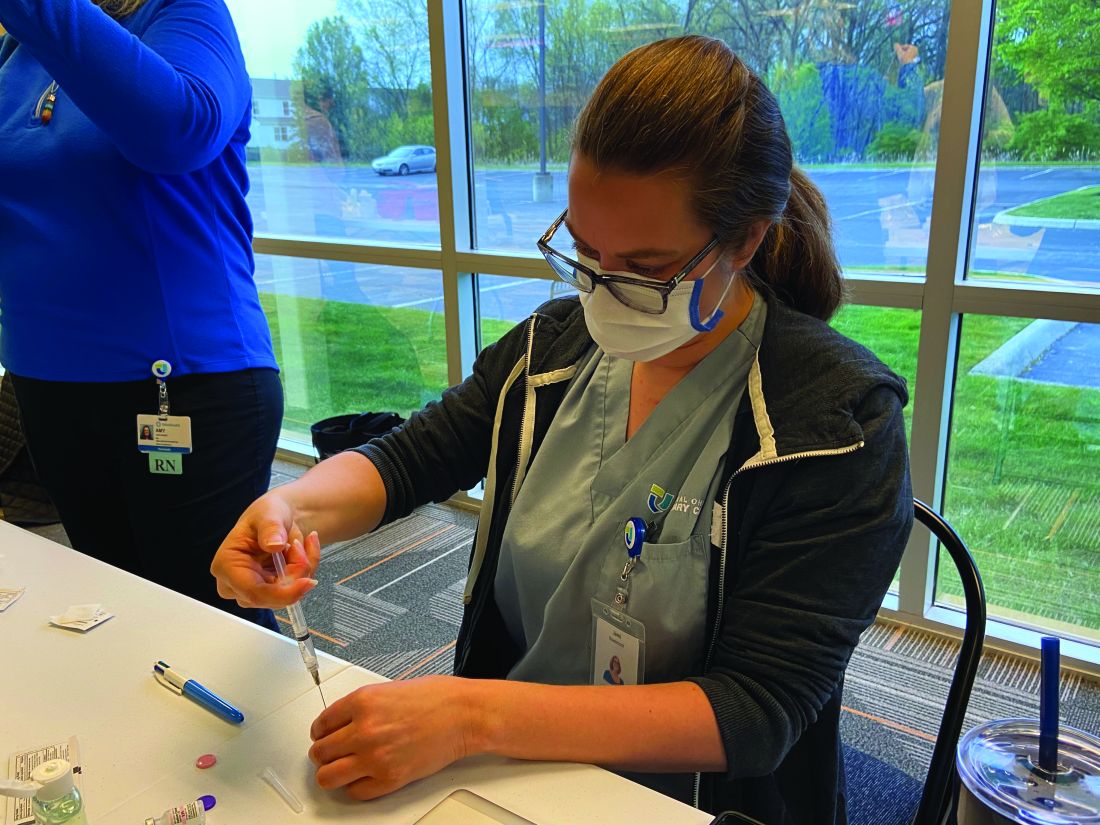

Nurses from Ms. Amer’s practice vaccinated approximately ten homebound patients with the J&J vaccine through a pilot program in March. Then on April 24, nurses from Central Ohio Primary Care vaccinated just under 40 homebound patients and about a handful of their caregivers who were not able to get their vaccines elsewhere, according to Ms. Amer. This time they used the Pfizer vaccine and will be returning to these patients’ homes on May 15 to administer the second dose.

“Any time you are getting in the car and adding miles, it adds complexity,” Ms. Amer said.

“We called patients 24 to 36 hours before coming to their homes to make sure they were ready, but we learned that just because the healthcare power of attorney agrees to a patient getting vaccinated does not mean that patient will be willing to get the vaccine when the nurse shows up," she noted.

Ms. Amer elaborated that three patients with dementia refused the vaccine when nurses arrived at their home on April 24.

“We had to pivot and find other people,” Ms. Amer. Her practice ended up having to waste one shot.