HUNTINGTON BEACH, CALIF. – Fewer herniations and gastroesophageal reflux complications were seen in children undergoing minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication than in those undergoing a more conventional procedure in a randomized trial of 177 patients.

In recent years, surgeons have debated whether it’s best during pediatric fundoplication to free the esophagus from the phrenoesophageal membrane or leave it embedded in that anatomical anchor.

The conventional approach allows the surgeon to pull a bit of the esophagus into the abdomen so that it can be wrapped with the gastric fundus, as is done in adults. The second approach leaves the esophagus and its attachments in place; the top of the stomach is simply wrapped around the gastroesophageal junction.

Not only does minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication control reflux at least as well as the conventional approach does, it also greatly reduces the likelihood that the fundal wrap and stomach will herniate into the chest cavity, said Dr. Shawn St. Peter at the annual Academic Surgical Congress.

The trial randomized 87 children to laparoscopic fundoplication with circumferential division of the phrenoesophageal attachments; 90 children were randomized to laparoscopic fundoplication with minimal esophageal mobilization and no violation of the phrenoesophageal membrane.

The groups had no statistically significant differences in preoperative reflux symptoms, weight, neurologic impairment, or other parameters. The mean age in both groups was about 2 years; slightly more than half were male.

Dr. St. Peter, a pediatric surgeon at the Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Mo., and five other surgeons each performed roughly equal numbers of both procedures.

At 1-year follow-up, the herniation rate by contrast study was 30% in children who had their phrenoesophageal membrane taken down, and 7.8% when it was left alone (P = .002).

Similarly, 18.4% of children in the take-down group needed at least one surgery to reduce a herniation; the redo rate in the minimal-dissection group was 3.3% (P = .006).

The minimal-dissection group also had fewer postop gastroesophageal reflux complications – weight loss, pneumonia, and acute life-threatening events – although the trend was not statistically significant (J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011;46:163-8).

"The results are very, very clear, and show that going forward we should be doing the minimal-dissection approach. This study should significantly change practice," said Dr. R. Lawrence Moss, surgeon-in-chief at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio.

"This is one of the most significant studies in [pediatric] surgery for a long time, and it sets a standard that technique questions can be answered in a scientific manner. It really raises the bar for all of us," said Dr. Moss, who did not participate in the trial but was familiar with its results.

The most satisfying outcome of the trial was the reduction in hernias, Dr. St. Peter said in an interview following his presentation.

Adults aren’t typically at risk for fundal wrap herniation; the adult diaphragm is strong enough to hold the wrap in place. In children, however, simple inhalation – because of negative chest pressure – can sometimes pop the wrap and stomach into the chest, where they get stuck on top of the diaphragm.

"Anybody who does fundos [in children] has at least one patient who has had that problem. It’s a nightmare," Dr. St. Peter said. Postoperative retching, vomiting, and gagging may occur, and attempts to reduce the hernia sometimes fail. If multiple attempts fail, the stomach may no longer empty properly, leaving children with chronic gastric pain and other long-term complications.

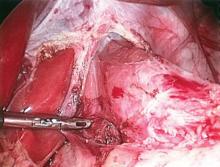

During minimal-dissection laparoscopic fundoplication, Dr. St. Peter takes down the gastrohepatic ligament up toward diaphragm, without touching the phrenoesophageal membrane. He then bluntly creates an opening into the abdomen directly behind the esophagus, preserving all the anterolateral attachments.

Without membrane dissection, the operation goes a bit faster. But surgeons must be careful: "Even gentle manipulation can be enough to free up the diaphragm from the esophagus in a baby," he said.

Dr. St. Peter and his colleagues are investigating whether esophagocrural sutures – which were placed in all trial subjects – are needed when the phrenoesophageal membrane is left intact.

Those sutures are important when it’s taken down, but "if you never open the door, putting four sutures in the seam of the door seems silly," Dr. St. Peter said.