BOCA RATON, FLA. — A new risk-stratification formula provides a practical means of predicting long-term survival likelihood after liver retransplantation for a failing allograft.

For the 22% of liver transplant recipients who develop graft failure, retransplantation offers the only salvage therapy. This new risk-scoring system can help to optimize utilization of a scarce resource by identifying a substantial patient subgroup for whom liver retransplantation is likely to be futile, Dr. Johnny C. Hong said at the annual meeting of the American Surgical Association.

Liver transplantation has become increasingly challenging in the last decade. Not only has the gap between donor organ supply and demand grown larger, but lately the donor organs are more often compromised in quality. Donors have become older and more obese, and often they have died of cardiac disease – all of which makes for a suboptimal liver for purposes of transplantation, noted Dr. Hong of the University of California, Los Angeles.

He presented a predictive index derived by analysis of the 466 liver retransplantations performed in 426 adult recipients at UCLA over the past 26 years. The recipients had a mean age of 49 years. In all, 90% of them had one prior liver transplant. The median interval between the previous transplant and retransplantation was 20 days. One-third of the patients required urgent retransplantation, and 56% were on mechanical ventilation prior to repeat transplantation. The median MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) score was 30, reflecting the high degree of acuity of their illness.

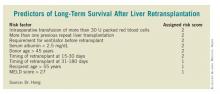

Multivariate analysis of more than 20 recipient, donor, and operative variables identified 8 independent predictors of retransplant graft failure. Each of these eight predictors was associated with a 20%-90% increased risk. Dr. Hong and his coworkers assigned each predictor a risk score of 1 or 2 based on its predictive strength. (See box.)

The 101 liver retransplants in the high-risk category (based on a total predictive score of 5-12 points) had a 5-year graft failure–free survival rate of only 20%. In contrast, this rate was 47% among the 335 intermediate-risk patients having a score of 1-4, and 65% in the 30 low-risk patients who had a score of 0.

The 5-year overall survival followed the same pattern (22% in the high-risk group, 53% in those at intermediate risk, and 79% in the small low-risk group).

Sepsis was the No. 1 cause of graft failure after repeat liver transplantation, accounting for 46% of the 272 cases, followed by recurrent disease (14%). Of note, despite the technical complexity of repeat transplantation surgery, vascular and biliary complications accounted for only 7% and 5% of graft failures, respectively.

Some 40% of repeat liver transplant recipients had recurrent hepatitis C. A notable finding was that their survival rate was no different from that of recipients without hepatitis C infection, Dr. Hong observed.

Discussant Dr. John Fung, chairman of the Digestive Disease Institute at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, congratulated Dr. Hong on presenting the largest-ever, single-center patient series on repeat liver transplantation. He wondered whether the predictive model might be enhanced by the elimination of intraoperative transfusion information and donor age from the equation, instead focusing entirely on the recipient factors. The reason for this proposal is that intraoperative blood loss can’t really be predicted at the time the transplant team is deciding whether to go ahead with retransplantation, and the donor age may not be known, either.

Dr. Hong replied that the formula would still work. For example, a patient with a history of more than one prior liver retransplant who requires mechanical ventilation, who has a MELD score greater than 27 and a serum albumin below 2.5 mg/dL, and who needs another liver 15-180 days after the prior transplant would have a risk score of 8, squarely within the high-risk category.

Dr. Hong declared having no financial conflicts.