ATLANTA – Surveillance data from Minnesota and Wellington, New Zealand, underscore the extent of the racial and ethnic disparities in the rates of influenza and hospitalization for influenza that occurred during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, and some of those data demonstrate that these disparities persisted at similar levels in 2010-2011.

The findings underscore the need for improved public health strategies that alleviate the socioeconomic factors that contribute to the disparities, the investigators agreed.

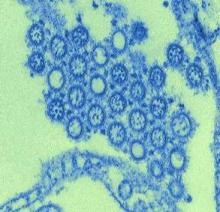

Photo courtesy CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith

Photo courtesy CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith

The findings of this study indicate that racial and ethnic disparities occurred to a similar degree during both 2009 and the 2010-2011 flu seasons, and suggest that more study is needed to further delineate the relationship between race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, vaccine coverage, prevalence of chronic illnesses, and access to health. This picture shows virons from a 2009 H1N1 isolate.

The combined incidence of hospitalization for influenza per 100,000 population in Minnesota during the pandemic influenza season in 2009 and the subsequent influenza season was 60.8 for blacks, 42.8 for Native Americans, 35.3 for Hispanics, 23.7 for Asians, and 17.8 for whites. Nonwhites accounted for 31% of cases during the pandemic period, and 23% during the following season, Craig Morin of the Minnesota Department of Health reported in a poster at the International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The median age of hospitalized patients during the 2009 pandemic was 28.8 years; the median age in the 2010-2011 season was 52.6 years.

"After adjustment for age, the relative rates associated with nonwhite vs. white non-Hispanic race was 2.46 during the 2009 pandemic period, and 2.52 during the 2010-2011 season," Mr. Morin wrote. The differences were statistically significant.

Cases included in this study were laboratory-confirmed, hospitalized influenza cases. During the pandemic season, cases included Minnesota residents hospitalized between April 2009 and April 2010 for confirmed A (H1N1) pmd09 influenza. During the subsequent season, cases included Minnesota residents hospitalized between October 2010 and April 2011 for laboratory-confirmed A H3 or A (H1N1) pmd09 influenza.

Ethnicity information was available for 1,703 cases during the pandemic period and for 467 cases during the subsequent season.

The findings indicate that racial and ethnic disparities occurred to a similar degree during both seasons, and suggest that more study is needed to further delineate the relationship between race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors, vaccine coverage, prevalence of chronic illnesses, and access to health care. A better understanding of these relationships would be helpful for designing public health interventions most likely to alleviate the disparities, Mr. Morin concluded.

Another study presented at the conference also demonstrated disparities in influenza rates and outcomes based on socioeconomic status. These findings among residents of New Zealand during the pandemic season also highlighted a need for public health interventions to reduce the factors contributing to disparities.

During the pandemic season, rates of infection were highest among the most socioeconomically deprived groups. For example, the rates were significantly higher among Pacific peoples than among European/other individuals (adjusted risk ratio, 1.49). Also, after the researchers adjusted for infection rates, they found that hospitalization rates were higher for Maori (adjusted risk ratio, 2.44), Pacific peoples (adjusted risk ratio, 4.16), and the most deprived socioeconomic status quintile of the population (adjusted risk ratio, 1.37). Mortality risk was also significantly higher for Pacific peoples (adjusted risk ratio, 3.28), Dr. Michael G. Baker of the University of Otaga, Wellington, reported at the conference.

Furthermore, general practitioner consultation rates were inversely associated with disease risk, and the rates of consultation were significantly lower for Maori and Pacific peoples and for those in more deprived quintiles after adjustment for infection rates, Dr. Baker said.

The findings reinforce the importance of identifying factors that contribute to elevated risk, reducing socioeconomic inequality, and improving access to primary care services for disadvantaged populations, he concluded.

Mr. Morin’s study was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emerging Infections Program. Neither Mr. Morin nor Dr. Baker had disclosures to report.