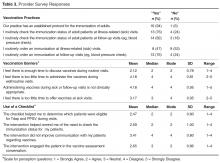

After the 3-month intervention period, an 18-item survey was distributed to participating providers to assess their vaccination practices, their perception of practice-related barriers to vaccinating, and their perception of the use of the checklist at the point of care. The survey included 5 demographic items, 5 Yes/No questions asking about the providers’ vaccination practices (adapted from [18]), and 8 questions asking about the providers’ perceptions of practice-specific vaccination barriers and the usefulness of the checklist. For these 8 questions providers were asked to choose a response along a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

Results

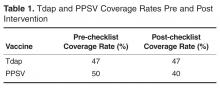

The pre- and post-intervention chart review revealed no improvement in the administration and uptake of PPSV or Tdap during the intervention period. Tdap coverage rate remained at 47% (14/30) before and during the intervention period. PPSV coverage rate decreased slightly during the intervention period to 40% (12/30) from a pre-intervention rate of 50% (15/30) ( Table 1 ).Of the 29 providers at the family practice, 17 participated in the survey. All but 1 participant completed the demographic questions. Demographic data for these 16 providers are presented in Table 2 .All providers responded to the vaccination practice-related questions. These questions and the frequency of responses are presented in Table 3 . At follow-up visits, such as those for blood pressure checks, 82% of the providers stated they checked the patient’s immunization status and 76% of providers stated they ordered an immunization. In contrast, although 76% of providers indicated they checked the immunization status, only 47% noted they routinely ordered a vaccine at a sick visit. A Fisher’s exact test of independence to examine the relationship between providers’ years of experience and decision to vaccinate at sick visits revealed a result that was not significant ( P = 1).

With regard to questions related to perceptions of vaccination barriers, providers believed administering vaccines during well, sick, and follow-up visits is appropriate and there is adequate time to do so. However, when asked if there was too little time to offer vaccines at sick visits, the providers answers were neutral (mean, 3.17 out of 5). Providers’ responses relative to the use of the checklist were mostly positive. The providers were most positive about the checklist helping them determine the patient’s eligibility for a vaccine during the visit (mean, 2.47 out of 5, with 1 indicating strong agreement). There was a generally wide range of answers to most of the questions.Discussion and Lessons Learned

Introduction of the reminder checklist at the point of care did not improve the administration or uptake of Tdap or PPSV during the intervention period. Limitations to our analysis include the small sample size. Also, this project was conducted in the fall, when influenza vaccines are usually given and providers may be more attuned to checking for vaccine eligibility. Future iterations of the project may be conducted to allow for samples over several months and use a process control chart to retrieve a more representative sample of participants from each vaccine-eligible group in the practice.