From the Children’s National Health System, Washington, DC (Dr. Manget, Dr. Kelley, Dr. White) and the Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC (Dr. Blood-Siegfried).

Abstract

- Background: Approximately 11% of children in the United States ages 4 to 17 have received the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD). There are disproportionately higher rates of the diagnosis and fewer child psychiatrists available in underserved areas. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) strongly encourages improved mental health competencies among primary care providers to combat this shortage.

- Objective: To improve primary care providers’ knowledge and confidence with the management of ADHD and institute an evidence-based process for assessing patients presenting with behavior concerns suggestive of ADHD.

- Methods: Three in-person educational sessions were conducted for primary care providers by a child psychiatrist to increase providers’ knowledge and confidence in the evaluation and management of ADHD. A Behavior Management Plan was also adopted for use in the clinic. Providers were encouraged to use the plan during patient visits for behavior concerns indicative of ADHD. Pre- and post-test surveys were given to providers to assess change in comfort level with managing ADHD. Patient charts were reviewed to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized.

- Results: We did not find significant changes in provider comfort in managing ADHD according to the survey results, although providers reported that the educational sessions and handouts were useful. Behavior Management Plans were utilized during 13 of 25 (52%) eligible visits.

- Conclusions: Behavior Management Plans were introduced in just over half of relevant visits. Further exploration about barriers to use of the plan and its utility to patients and families should be pursued in the future. Additionally, ongoing opportunities for continuing education and collaboration with psychiatry should continue to be sought.

Keywords: attention-deficit hyperactive disorder; ADHD; AAP clinical guidelines; underserved populations; disadvantaged communities.

The importance of the mental health of a child cannot be underestimated. Untreated symptoms of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can significantly interfere with school and social functioning [1]. Children with ADHD often have comorbid conditions such as anxiety, low self-esteem and learning disabilities. It is vital to screen and treat for ADHD and comorbidities early and comprehensively [2].

There are disproportionately higher rates of children diagnosed with ADHD living in underserved areas compared to other geographical regions [3]. The historically underserved Southeast region of Washington D.C. which encompasses Wards 7 and 8 is home to nearly 40% of the district’s children and has the highest rates of children with an ADHD diagnosis in D.C.; however, the majority of child psychiatrists are located in the Northwest regions [4]. In 2009, nearly 8% of children in Washington D.C. were reported to have a diagnosis of ADHD [1].

Due to the overwhelming demand and limited availability of child psychiatrists, it is important that primary care providers become better equipped to diagnose, treat, and manage non-complex cases of ADHD. Specific education about ADHD diagnosis and management along with implementation of standardized center-based processes may help primary care providers feel more comfortable caring for these patients and ensure that all patients presenting with behavior concerns are adequately assessed and treated.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that primary care providers expand their mental health competencies because pediatric primary care providers in the medical home will be the first point of access in most cases [5]. In 2011, the AAP Subcommittee on ADHD and Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management released clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of ADHD [6]. These guidelines, which recommend that providers should initiate ADHD assessments for children ages 6 to 12 that present with behavioral and/or academic problems, have been incorporated into “Caring for Children with ADHD: A Resource Toolkit for Clinicians” by the AAP in partnership with the National Institute on Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) and North Carolina’s Center for Child Health.

Our clinic has two on-site psychiatrists who provide evaluation and treatment of mental health problems in children identified by primary care providers for a combined total of 1.5 days each week. The current wait for psychiatric evaluation at our clinic is 2 to 3 months, which leaves the primary care providers to care for many children with behavior concerns who require more immediate intervention at the time of their presentation. Our clinic providers revealed that they felt there were deficits in the management of behavior concerns and initiating treatment for patients diagnosed with ADHD in the clinic. Providers expressed an interest in refreshing and enhancing their knowledge related to managing patients with ADHD.

To address this issue, we initiated a quality improvement project with several facets: provide ADHD education to primary care providers through use of educational sessions from our on-site psychiatrists, standardize the process of managing patients that present with behavior concerns to the primary care provider in the medical home, and develop a comprehensive and individualized patient management plan based on the “Caring for Children with ADHD” toolkit for clinicians.

Methods

Setting

This project took place in a federally qualified health center located in the Southeast quadrant of Washington, D.C. that serves patients up to 23 years of age. The clinic has 6 primary care medical providers (5 physicians and 1 nurse practitioner) employed in a part-time to full-time capacity. Additionally, 2 child psychiatrists provide services on-site during one full day and one half-day session on a weekly basis. Approximately 98% of patients at the clinic are classified as African American and close to 95% of patients are insured by Medicaid. Approximately 9% of patients in our clinic had a medical diagnosis of ADHD as of 2015.

Patients who presented to the clinic in April and May 2017 who had an existing diagnosis of ADHD and those with documentation of a new behavior concern in the assessment and treatment plan were studied. Eligible visit types were annual well-child checks, new consults for behavior, and follow-up appointments specifically for behavior.

This was a project undertaken as a quality improvement initiative at the hosting facility and did not constitute human subjects research. As such, it was not under the oversight of the institutional review board.

Intervention

Provider Education. Three in-person sessions were held at the clinic during April–May 2017 to provide education on the assessment and treatment of patients with ADHD and discuss challenges that have arisen when providing care for such patients. The sessions focused on diagnosing ADHD and teasing out comorbidities; initiating and titrating medications safely; educational rights; and strategies for managing behavior and community resources.

Current providers as well as medical residents and student trainees of the clinic were invited to attend the educational sessions. Each session followed a “lunch and learn” format where one of the clinic psychiatrists presented the information during the clinic lunch hour then related a discussion where participants asked questions. The information provided was derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) and the AAP/NICHQ Toolkit [5]. Educational handouts were disseminated during the provider sessions and emailed to all providers afterwards.

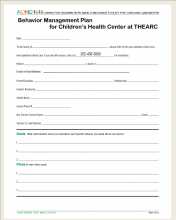

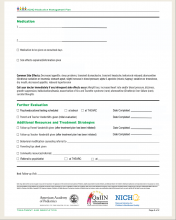

Behavior Management Plan. In March we introduced the providers to the Behavior Management Plan (Figure),

which we adapted from the 2011 AAP/NICHQ Toolkit [5]. The Behavior Management Plan was intended for use during all clinic visits with a presenting complaint suggestive of ADHD. The plan, when completed with the family, helps ensure a comprehensive assessment has been performed and details specific individualized patient goals and the plans to reach them. It encourages families to complete Vanderbilt ADHD assessment scales and instructs them to have teachers complete and return them. Vanderbilt Assessment Scales were published by the AAP and NICHQ in 2002 as a tool to aid in the diagnosis of ADHD for children between the ages of 6 and 12 [7]. The Behavior Management Plan also encourages the providers to offer parents useful handouts, sample letters to the school and referrals to community agencies. Lastly, it advises families to return for subsequent clinic visits and gives the family a clear date and instructions for follow-up.Providers were encouraged to initiate the Behavior Management Plan for patients that presented without an existing diagnosis for evaluation of their behavior concerns. The plan could also be used for patients that had previously been diagnosed with ADHD if changes were being made to their treatment plan or as a summary of their established treatment details. Instructions on the use of the plan were given to all clinic primary care providers through email communication as well as in the first in-person educational session. It was stressed to providers that formulating individual patient goals and the inclusion of a specific follow-up time were the most important aspects of the plan.

Assessment and Measurements

We assessed provider comfort in their ADHD evaluation and management skills before and after the intervention using a 5–point Likert scale questionnaire with 0 indicating “not comfortable at all” and 5 corresponding to “very comfortable.” The questionnaire was administered via a paper survey for the initial screening and an electronic survey at the conclusion of the intervention.

Patient charts were reviewed in July 2017 to determine how often the Behavior Management Plan was utilized. Provider documentation in the electronic medical record indicating that the Plan was given during the patient visit was considered utilization of the plan. We also examined documentation of dissemination/return of Vanderbilt ADHD assessment scales, referrals to psychiatry or counseling, and the initiation or refill of an ADHD medication during the encounter for all patients that were seen for behavior concerns. Patient data were obtained from manual chart review of the electronic medical record, eClinicalWorks.