Interpreting the Results of Reactive Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

The implementation of reactive TDM involves obtaining a serum drug and antibody level and then interpreting what those results suggest about the mechanism of drug failure, in order to decide on a course of action. The serum drug level should be a trough concentration, so it should be obtained just prior to a timed dose, while on a stable treatment regimen. Exactly what serum drug concentration we should be targeting in reactive therapeutic drug monitoring remains an area of investigation. No RCTs have been published. There is ample observational, cross-sectional data from cohorts of patients on maintenance therapy, though heterogeneity in study design and study populations, as well as use of different assays, limit interpretation of the data. In a secondary analysis of data from 6 observational studies of patients on infliximab maintenance therapy, there was a highly statistically significant concentration-dependent trend in rates of clinical remission depending on the measured infliximab trough concentration, with 96% of those with infliximab > 7 μg/mL in remission, 92% of those with infliximab > 5 μg/mL in remission, and 75% of those with infliximab > 1 μg/mL in remission. Likewise, data from 4 studies of patients receiving adalimumab showed a statistically significant concentration-dependent trend in clinical remission, with 90% of those with adalimumab trough concentrations > 7.5 μg/mL being in clinical remission, compared with only 83% of those with concentrations > 5 μg/mL. Similarly, data from 9 studies suggested that a certolizumab trough concentration > 20 μg/mL was associated with a 75% probability of being in clinical remission, compared to a 60% probability when the trough concentration was > 10 μg/mL [9]. Based on these analyses, the AGA suggests target trough concentrations for reactive therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-TNF agents of ≥ 5 μg/mL for infliximab, ≥ 7.5 μg/mL for adalimumamb, and ≥ 20 μg/mL for certolizumab. They did not suggest a target trough concentration for golimumab because of insufficient evidence [8].

When interpreting TDM test results, it is important to know if the test you have used is drug-sensitive or drug-tolerant (Table 2). Drug-sensitive tests will be less likely to reveal the presence of anti-drug antibodies when the drug level is above a certain threshold. A post-hoc analysis of the TAXIT trial recently suggested that subjects who have antibodies detected on a drug-tolerant test which were not detected on a drug-sensitive test are more likely to respond to higher doses of infliximab [19]. It follows that there should be a threshold anti-drug antibody titer below which someone who has immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure will still respond to TNF antagonist dose escalation, but above which they will fail to respond to dose escalation. To be sure, our understanding of the clinical implications of a drug-tolerant test demonstrating an adequate drug level while also detectable anti-drug antibodies is evolving. Complicating the issue further is the fact that anti-drug antibody concentrations cannot be compared between assays because of assay-specific characteristics. As such, though the presence of low antibody titers and high antibody titers seems to be clinically important, recommendations cannot yet be made on how to interpret specific thresholds. Furthermore, development of transient versus sustained antibodies requires further clinical investigation to determine impact and treatment algorithms.

Optimizing Therapy

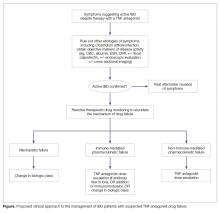

Once you have determined the most likely cause of drug failure, the next step is to make a change in medical therapy.

As described above, and detailed in the Figure, this will likely involve switching to a drug of a different class when mechanistic failure is invoked, dose escalation and/or the addition of an immunomodulatory agent when non-immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure is invoked, and switching either within class (to another anti-TNF) or outside of drug class when immune-mediated pharmacokinetic failure is invoked [8].When switching within class (to another anti-TNF agent), the choice of which agent to use next will largely depend on patient preference (route of administration, infusion versus injection), insurance, and costs of treatment. When making the decision to switch within class, it should be kept in mind that the probability of achieving remission is modestly reduced compared to the probability seen in anti-TNF-naive patients [20], and even more so when the patient is switching to their third anti-TNF agent [21]. Thus, for the patient who has already previously switched from one TNF antagonist to a second TNF antagonist, it may be better to switch to a different class of biologic rather than attempting to capture a clinical remission with a third TNF antagonist.

When adding an immunomodulator (azathioprine or methotrexate), the expectation is that the therapy will increase the serum concentration of the anti-TNF agent [14] and/or reduce the ongoing risk of anti-drug antibody formation [22]. There could also be a direct treatment effect on the bowel disease by the immunomodulator.

When switching to an alternate mechanism of action, the currently FDA-approved options include the biologic agents vedolizumab (for both moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis and moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease) and ustekinumab (for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease), as well as the recently FDA-approved oral, small-molecule JAK1 and JAK3 inhibitor tofacitinib (for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis). Prospective comparative effectiveness studies for these agents are lacking and are unlikely to be performed in part due to the cost and time required to accomplish these studies. A recent post-hoc analysis of clinical trials data suggests that there are no significant differences in the rates of clinical response, clinical remission, or in adverse outcomes to vedolizumab or ustekinumab when they are used in patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy [23]. Thus, one cannot be recommended over the other, and the decision of which to use is usually guided by patient preference and insurance coverage.

Meanwhile, the role of tofacitinib in the treatment algorithm of patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy remains unclear. The phase III clinical trials OCTAVE 1, OCTAVE 2, and OCTAVE Sustain showed efficacy for both the induction and maintenance of remission in patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis who had previously failed anti-TNF agents. However, there remain concerns about the safety profile of tofacitinib compared to vedolizumab and ustekinumab, particularly regarding herpes zoster infection, dyslipidemia, and adverse cardiovascular events. Notable findings from the tofacitinib induction trials include robust rates of clinical remission (18.5% vs 8.2% for placebo in Octave 1, and 16.6% vs 3.6% in Octave 2, P < 0.001 for both comparisons) and mucosal healing (31.3% vs 15.6% for placebo in Octave 1, and 28.4% and 11.6% in Octave 2, P < 0.001 for both comparisons) after 8 weeks of induction therapy [24]. These results suggest that tofacitinib, or other JAK inhibitors that become approved in the future, may be excellent oral agents for the induction of remission in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis, and may demonstrate a better side effect profile than steroids. Whether cost factors (compared to steroid therapy) will limit the role of JAK-inhibitor therapy in induction, and whether safety concerns will limit their use in maintenance therapy, remains to be seen.