THE CASE

Emily T,* a 30-year-old woman, visited her primary care physician as follow-up to reassess her grief over the loss of her father a year earlier. Emily was her father’s primary caretaker and still lived alone in his home. Emily had a history of chronic pain and major depressive disorder and had expressed feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness about her future since her father’s passing. In addition to her continuing grief response, she reported feeling worse on most days. She completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, and results indicated anhedonia, depressed mood, psychomotor retardation, hypersomnia, decreased appetite, decreased concentration, and thoughts that she would be better off dead.

- HOW WOULD YOU PROCEED WITH THIS PATIENT?

* The patient’s name has been changed to protect her identity.

In the United States, 1 suicide occurs on average every 12 minutes; lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts ranges from 1.9% to 8.7%.1 Suicide is the 10th overall cause of death in the United States, and it is the second leading cause of death for adults 18 to 34 years of age.2 In one study, nearly half of suicide victims had contact with primary care providers within 1 month of their suicide.3 Unfortunately, additional research suggests that primary care physicians appropriately screen for suicide in fewer than 40% of patient encounters.4,5

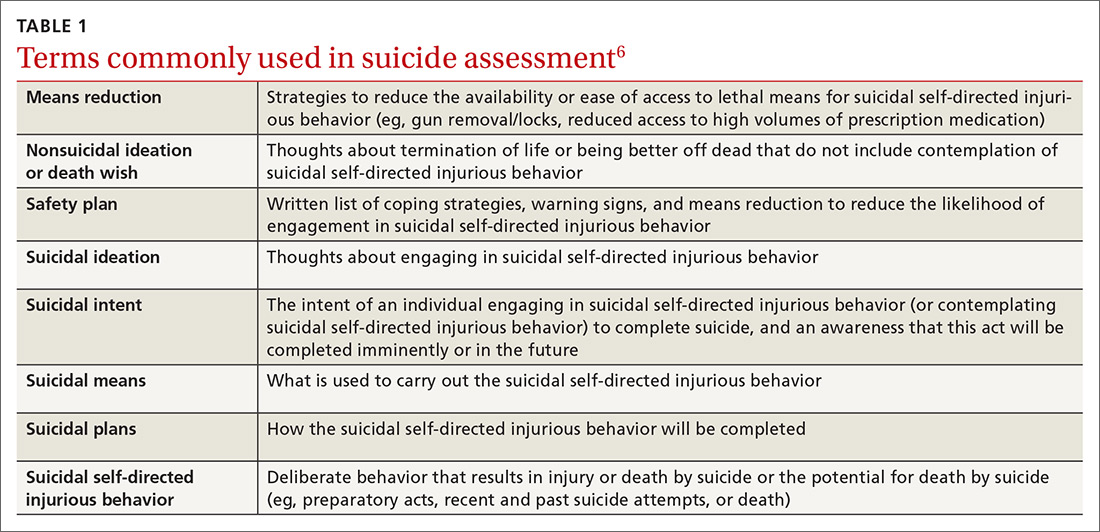

Suicide is defined as “death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior.”6 When screening for suicide, be aware of the many terms related to suicide evaluation (TABLE 16). Be mindful, too, of the differences between suicidal and nonsuicidal ideation (death wish); the continuum of such thoughts ranges from those that lead to suicide to those that do not.

SUICIDE SCREENING RECOMMENDATIONS VARY

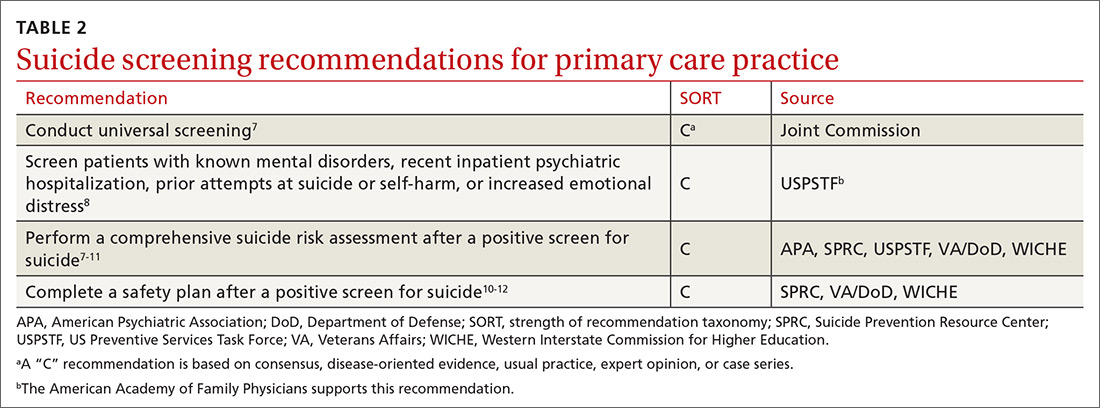

Although most health care providers would agree that intervening with a suicidal patient first requires competence in assessing suicide risk, regulating bodies differ on the use of routine screening and on appropriate screening tools for primary care. The Joint Commission recommends assessing suicide risk with all primary care patients,7 while the US Preventive Services Tasks Force (USPSTF) advises against universal suicide screening in primary care8 due to insufficient evidence that its benefit outweighs potential harm (TABLE 27-12). Instead, the USPSTF recommends screening primary care patients with known mental health disorders, recent inpatient psychiatric hospitalization, prior suicide or self-harm attempts, or increased emotional distress.8 USPSTF does support screening for depression with routine mental health measures that include items assessing suicidality.8,13,14 The American Academy of Family Physicians supports the recommendations by USPSTF.13

When screening for suicide, a comprehensive suicide risk assessment is recommended by both the Joint Commission and USPSTF.7,8 A comprehensive suicide risk assessment has 4 components: (1) identification of current suicide risk factors, (2) identification of protective factors, (3) inquiry about suicidal ideation, intent, and plan, and (4) primary care practitioner judgment of risk level and plan for clinical intervention.9-11

Take into account both risks and protective factors

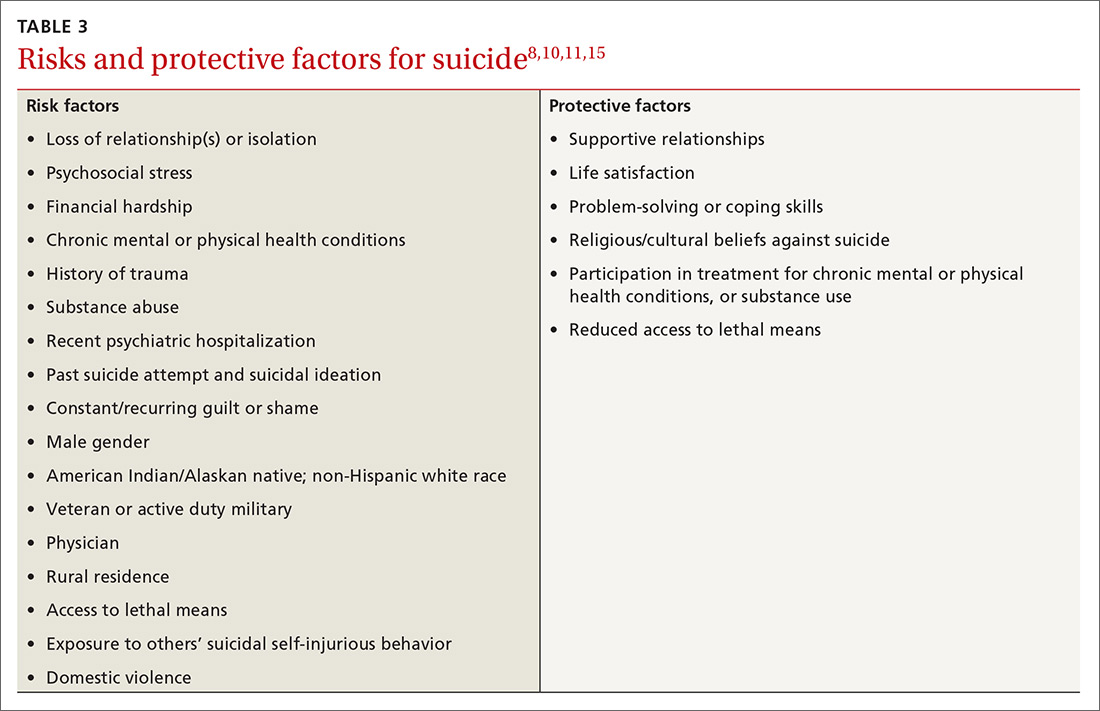

Unfortunately, there is no “typical” description of a patient at risk for suicide and no validated models to predict suicide risk.8,10 A multitude of factors, both individual and societal, can increase or reduce risk of suicide.11,15 Each patient’s unique history includes risk factors for suicide including precipitating events (eg, job loss, termination of a relationship, death of a loved one) and protective factors that may be evaluated to determine overall risk for suicide (TABLE 38,10,11,15). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there are several warning signs for patients who may be at greater risk for suicide: isolation, increased anxiety or anger, obtaining lethal means (eg, guns, knives, ropes), frequent mood swings, sleep changes, feeling trapped or in pain, increased substance use, discussing plans for death or wishes of death, and feeling like a burden.16

CHOOSING FROM AMONG SUICIDE SCREENING TOOLS

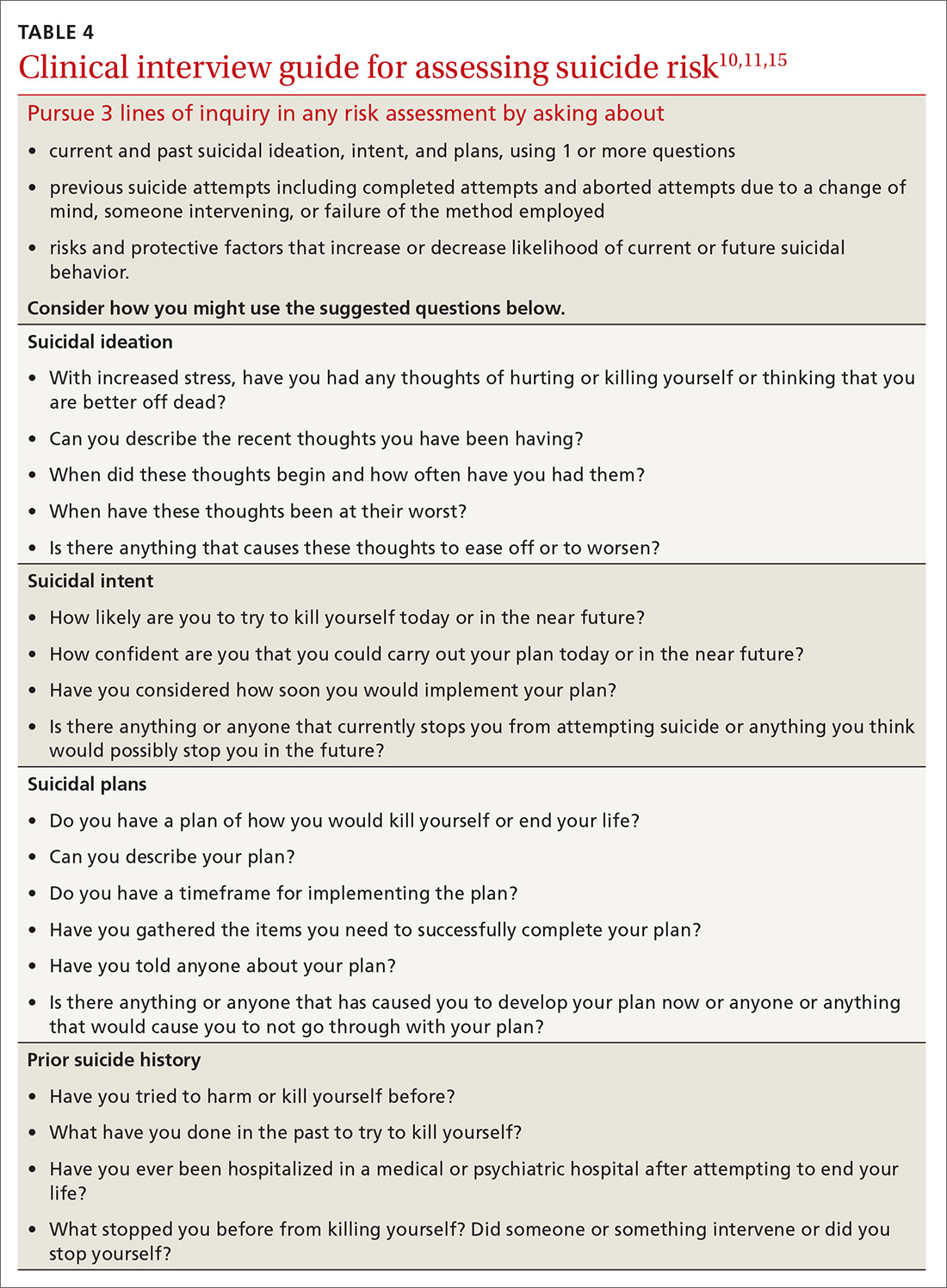

Brief mental health screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) are commonly used as primary screening tools for suicidal ideation.17 However, to attain a fuller understanding of a patient’s suicidality, select a screening tool that specifically focuses on suicidal ideation, intent, or plan, and then interview the patient (TABLE 410,11,15).

Continue to: Several screening tools...