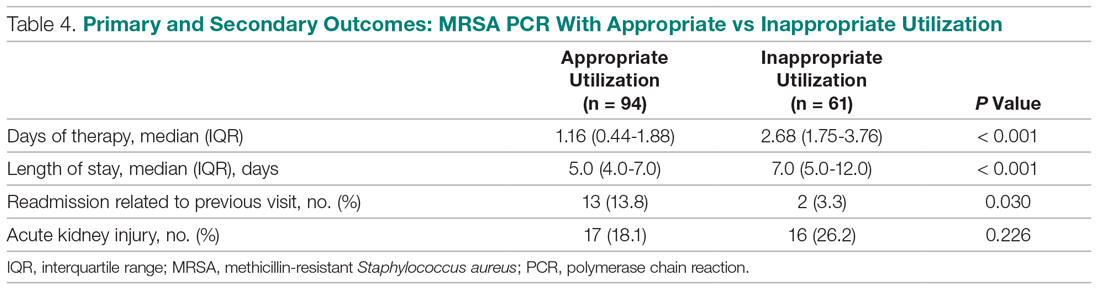

In the subgroup analysis, anti-MRSA DOT in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization was shorter than DOT in the MRSA PCR group with inappropriate utilization (1.16 [IQR, 0.44-1.88] vs 2.68 [IQR, 1.75-3.76] days, P < 0.001; Table 4). LOS in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization was shorter than LOS in the inappropriate utilization group (5.0 [IQR, 4.0-7.0] vs 7.0 [IQR, 5.0-12.0] days, P < 0.001). Thirty-day readmissions that were related to the previous visit were significantly higher in patients in the MRSA PCR group with appropriate utilization (13 vs 2, P = 0.030). There was no difference in incidence of AKI between the groups.

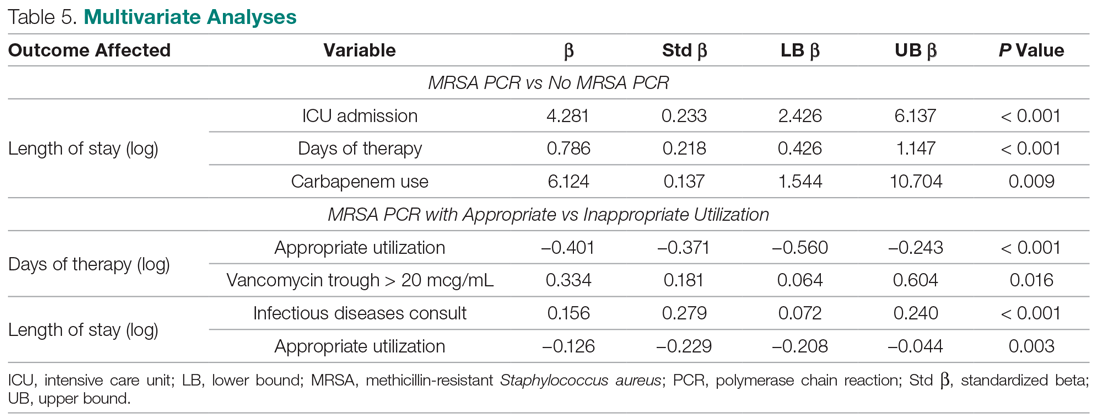

A multivariate analysis was completed to determine whether the sicker MRSA PCR population was confounding outcomes, particularly the secondary outcome of LOS, which was noted to be longer in the MRSA PCR group (Table 5). When comparing LOS in the MRSA PCR and the no MRSA PCR patients, the multivariate analysis showed that admission to the ICU and carbapenem use were associated with a longer LOS (P < 0.001 and P = 0.009, respectively). The incidence of admission to the ICU and carbapenem use were higher in the MRSA PCR group (P = 0.001 and P = 0.047). Therefore, longer LOS in the MRSA PCR patients could be a result of the higher prevalence of ICU admissions and infections requiring carbapenem therapy rather than the result of the MRSA PCR itself.

Discussion

A MRSA PCR nasal swab protocol can be used to minimize a patient’s exposure to unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotics, thereby preventing antimicrobial resistance. Thus, it is important to assess how our health system is utilizing this antimicrobial stewardship tactic. With the MRSA PCR’s high NPV, providers can be confident that MRSA pneumonia is unlikely in the absence of MRSA colonization. Our study established a NPV of 98.5%, which is similar to other studies, all of which have shown NPVs greater than 95%.5-8 Despite the high NPV, this study demonstrated that only 51.4% of patients with LRTI had orders for a MRSA PCR. Of the 155 patients with a MRSA PCR, the test was utilized appropriately only 60.6% of the time. A majority of the inappropriately utilized tests were due to MRSA PCR orders placed more than 48 hours after anti-MRSA therapy initiation. To our knowledge, no other studies have assessed the clinical utility of MRSA PCR nasal swabs as an antimicrobial stewardship tool in a diverse health system; therefore, these results are useful to guide future practices at our institution. There is a clear need for provider and pharmacist education to increase the use of MRSA PCR nasal swab testing for patients with LRTI being treated with anti-MRSA therapy. Additionally, clinician education regarding the initial timing of the MRSA PCR order and the proper utilization of the results of the MRSA PCR likely will benefit patient outcomes at our institution.

When evaluating anti-MRSA DOT, this study demonstrated a reduction of only 0.18 days (about 4 hours) of anti-MRSA therapy in the patients who received MRSA PCR testing compared to the patients without a MRSA PCR ordered. Our anti-MRSA DOT reduction was lower than what has been reported in similar studies. For example, Baby et al found that the use of the MRSA PCR was associated with 46.6 fewer hours of unnecessary antimicrobial treatment. Willis et al evaluated a pharmacist-driven protocol that resulted in a reduction of 1.8 days of anti-MRSA therapy, despite a protocol compliance rate of only 55%.9,10 In our study, the patients in the MRSA PCR group appeared to be significantly more ill than those in the no MRSA PCR group, which may be the reason for the incongruences in our results compared to the current literature. Characteristics such as ICU admissions, positive chest radiographs, sepsis cases, pulmonary consults, and carbapenem usage—all of which are indicative of a sicker population—were more prevalent in the MRSA PCR group. This sicker population could have underestimated the reduction of DOT in the MRSA PCR group compared to the no MRSA PCR group.

After isolating the MRSA PCR patients in the subgroup analysis, anti-MRSA DOT was 1.5 days shorter when the test was appropriately utilized, which is more comparable to what has been reported in the literature.9,10 Only 60.6% of the MRSA PCR patients had their anti-MRSA therapy appropriately managed based on the MRSA PCR. Interestingly, a majority of patients in the inappropriate utilization group had MRSA PCR tests ordered more than 48 hours after beginning anti-MRSA therapy. More prompt and efficient ordering of the MRSA PCR may have resulted in more opportunities for earlier de-escalation of therapy. Due to these factors, the patients in the inappropriate utilization group could have further contributed to the underestimated difference in anti-MRSA DOT between the MRSA PCR and no MRSA PCR patients in the primary outcome. Additionally, there were no notable differences between the appropriate and inappropriate utilization groups, unlike in the MRSA PCR and no MRSA PCR groups, which is why we were able to draw more robust conclusions in the subgroup analysis. Therefore, the subgroup analysis confirmed that if the results of the MRSA PCR are used appropriately to guide anti-MRSA therapy, patients can potentially avoid 36 hours of broad-spectrum antibiotics.