From T1D Exchange, Boston, MA (Dr. Ebekozien, Dr. Odugbesan, and Nicole Rioles); Barbara Davis Center, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO (Dr. Majidi); Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH (Dr. Jones); and Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH (Dr. Kamboj)

Health equity has been described as the opportunity for all persons to obtain their highest level of health possible.1 Unfortunately, even with advances in technology and care practices, disparities persist in health care outcomes. Disparities in prevalence, prognosis, and outcomes still exist in diabetes management.2 Non-Hispanic Black and/or Hispanic populations are more likely to have worse glycemic control,3,4 to encounter more barriers in access to care,5 and to have higher levels of acute complications,4 and to use advanced technologies less frequently.4 Diabetes is one of the preexisting conditions that increase morbidity and mortality in COVID-19.6,7 Unfortunately, adverse outcomes from COVID-19 also disproportionately impact a specific vulnerable population.8,9 The urgent transition to managing diabetes remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic may exacerbate long-term inequities because some vulnerable patients might not have access to technology devices necessary for effective remote management.

Here, we describe how quality improvement (QI) tools and principles can be adapted into a framework for advancing health equity. Specifically, we describe a 10-step framework that may be applied in diabetes care management to achieve improvement, using a hypothetical example of increasing use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) among patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.10 This framework was developed to address the literature gap on practical ways health care providers can address inequities using QI principles, and was implemented by 1 of the authors at a local public health department.11 The framework’s iterative and comprehensive design makes it ideal for addressing inequities in chronic diseases like diabetes, which have multiple root causes with no easy solutions. The improvement program pilot received a national model practice award.11,12

10-Step Framework

Step 1: Review program/project baseline data for existing disparities. Diabetes programs and routine QI processes encourage existing data review to determine how effective the current system is working and if the existing process has a predictable pattern.13,14 Our equity-revised framework proposes a more in-depth review to stratify baseline data based on factors that might contribute to inequities, including race, age, income levels, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, insurance type, and zip code. This process will identify patients not served or unfairly impacted due to socioeconomic factors. For example, using the hypothetical example of improving CGM use, a team completes a preliminary data review and determines that baseline CGM use is 30% in the clinic population. However, in a review to assess for disparities, they also identify that patients on public insurance have a significantly lower CGM uptake of only 15%.

Step 2: Build an equitable project team, including patients with lived experiences. Routine projects typically have clinicians, administrative staff, and analytic staff as members of their team. In a post-COVID-19 world, every team needs to learn directly from people impacted and share decision-making power. The traditional approach to receiving feedback has generally been to collect responses using surveys or focus groups. We propose that individuals/families who are disproportionately impacted be included as active members on QI teams. For example, in the hypothetical example of the CGM project, team members would include patients with type 1 diabetes who are on public insurance and their families.

Step 3: Develop equity-focused goals. The traditional program involves the development of aims that are SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-bound).15 The proposed framework encourages the inclusion of equity-revised goals (SMARTer) using insights from Steps 1 and 2. For example, your typical smart goal might be to increase the percentage of patients using CGM by 20% in 6 months, while a SMARTer goal would be to increase the proportion of patients using CGM by 20% and reduce the disparities among public and private insurance patients by 30% in 6 months.

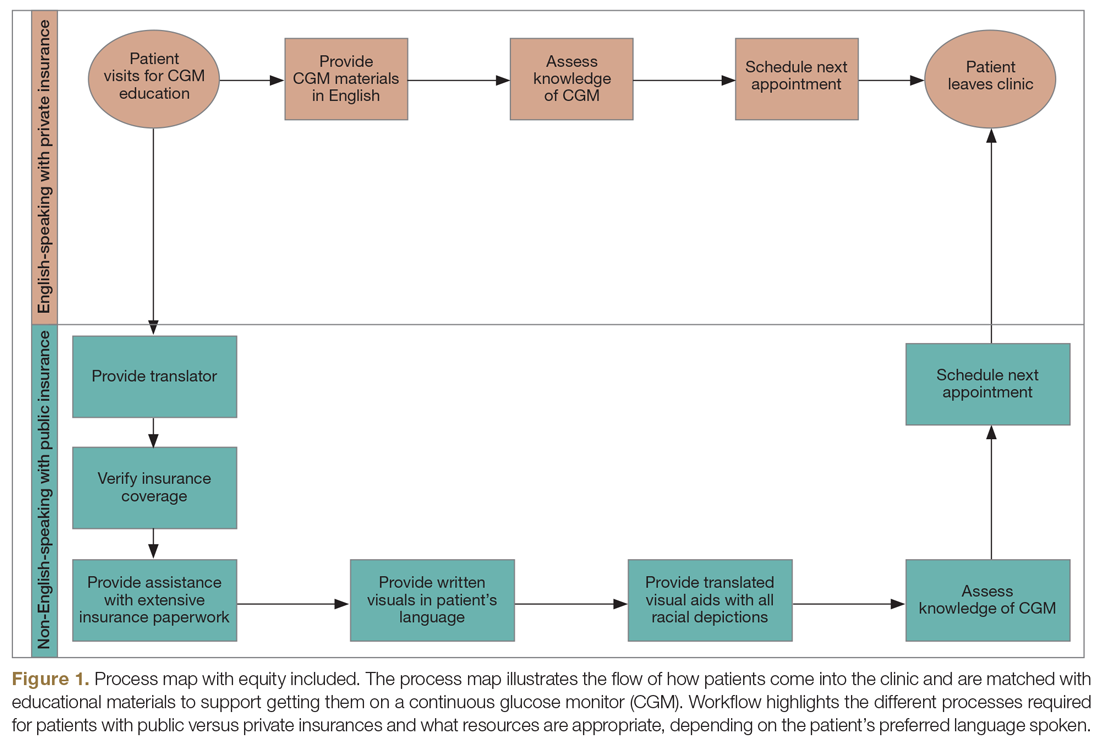

Step 4: Identify inequitable processes/pathways. Traditional QI programs might use a process map or flow diagram to depict the current state of a process visually.16 For example, in Figure 1, the process map diagram depicts some differences in the process for patients with public insurance as opposed to those with private insurance. The framework also advocates for using visual tools like process maps to depict how there might be inequitable pathways in a system. Visually identifying inequitable processes/pathways can help a team see barriers, address challenges, and pilot innovative solutions.