Results

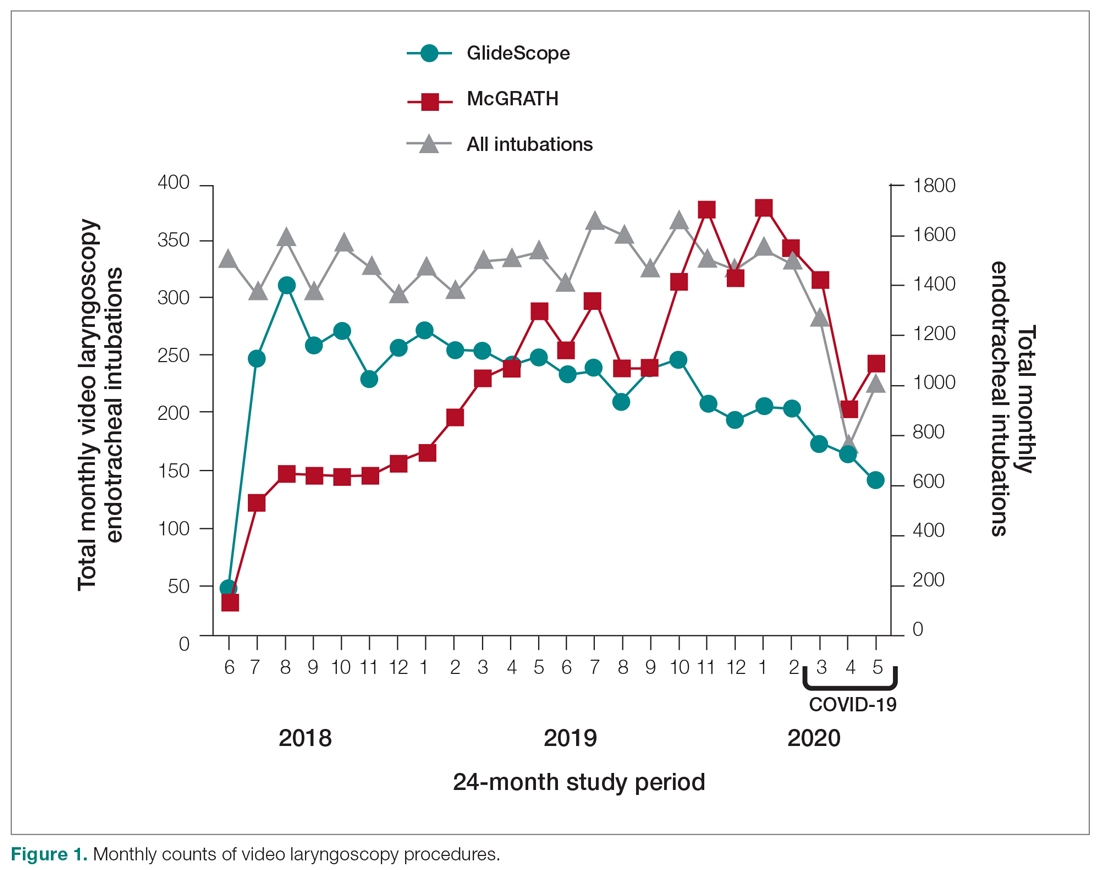

A total of 34 600 endotracheal intubations were performed over the 24-month study period, and 11 345 (32.8%) were video laryngoscopy procedures. Out of all video laryngoscopy procedures, 5501 (48.5%) were performed using the McGRATH VL and 5305 (46.8%) were conducted using the GlideScope VL. The difference of 539 (4.8%) cases accounts for flexible bronchoscopy procedures and endotracheal intubations using other video laryngoscopy equipment. The mean (SD) monthly number of video laryngoscopy procedures for the 24 months was 221 (54) and 229 (89) for the GlideScope and McGRATH devices, respectively. Monthly endotracheal intubation distributions over 24 months trended upward for the McGRATH VL and downward for the GlideScope, but there was no statistically significant (P = .71) difference in overall use between the 2 instruments (Figure 1).

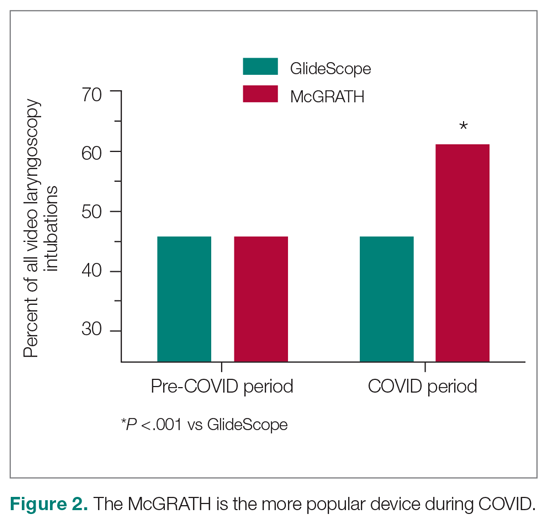

To examine the observed usage trends between the 2 VL during the first and last 12 months, a univariate ANOVA was conducted with the 2 time periods entered as predictors in the model. Video laryngoscopy intubations were performed (P = .001) more frequently with the GlideScope during the first 12 months; however, use of the McGRATH VL increased (P < .001) during the following 12 months compared to GlideScope. The GlideScope accounted for 54% of all VL intubations during the first 12 months, with the McGRATH accounting for 58% of all video laryngoscopy procedures for months 12 to 24. Additionally, the increase in video laryngoscopy procedures with the McGRATH during the last 3 months of the study period was despite an overall reduction in surgical volume due to the COVID-19 crisis, defined for this study as March 1, 2020, to May 31, 2020 (Figure 1). There was a statistically significant (P < .001) difference in the case distribution between use of the McGRATH and GlideScope VL for that period. The anesthesia personnel’s use of the McGRATH VL increased to 61% of all video laryngoscopy cases, compared to 37% for the GlideScope (Figure 2).

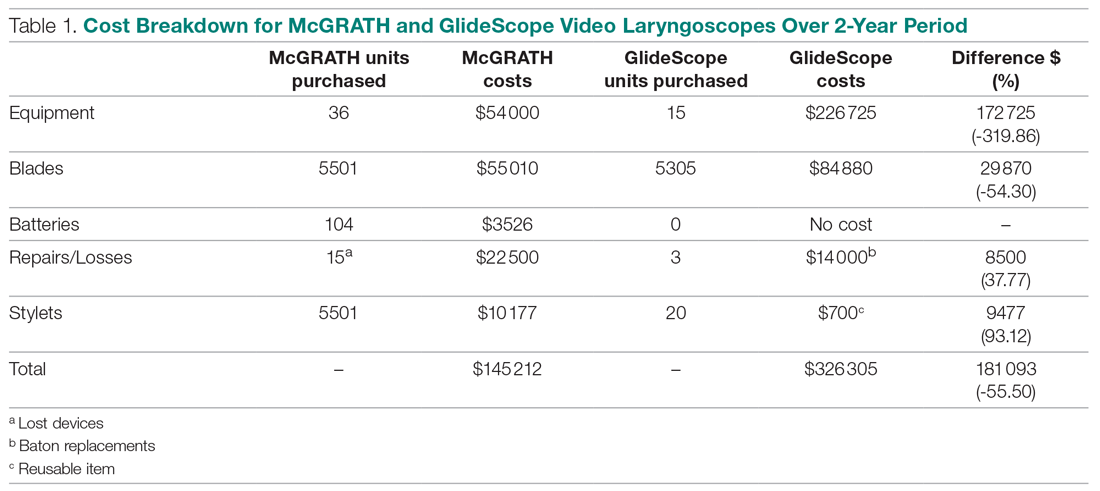

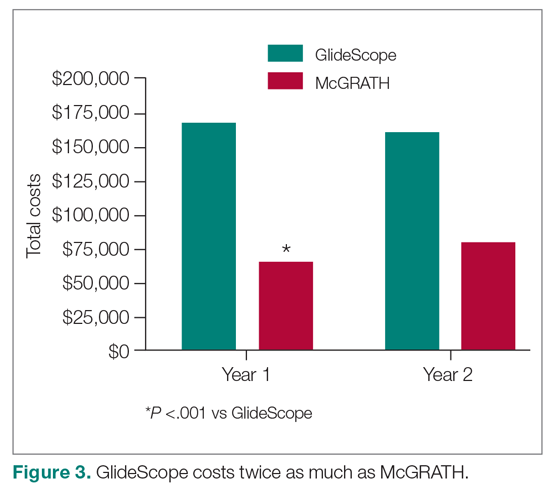

The total costs calculated for equipment, blades, and repairs are presented in Table 1 and yearly total costs are shown in Figure 3. Overall costs were $181 093 lower (55.5%) for the McGRATH VL compared to the GlideScope over the 24-month period. The mean (SD) monthly costs for GlideScope VL blades were $3837 ($1050) and $3236 ($538) for years 1 and 2, respectively, vs $1652 ($663) and $2933 ($585) for the McGRATH VL blades. Most of the total cost differences were attributed to equipment and blade purchases, which were $202 595 (65.0%) higher for the GlideScope compared to the McGRATH VL. The monthly blade costs alone were higher (P < .001) for the GlideScope over the 2-year period; however, the McGRATH VL required use of disposable stylets at a cost of $10 177 for all endotracheal intubations, compared to $700 for the GlideScope device.

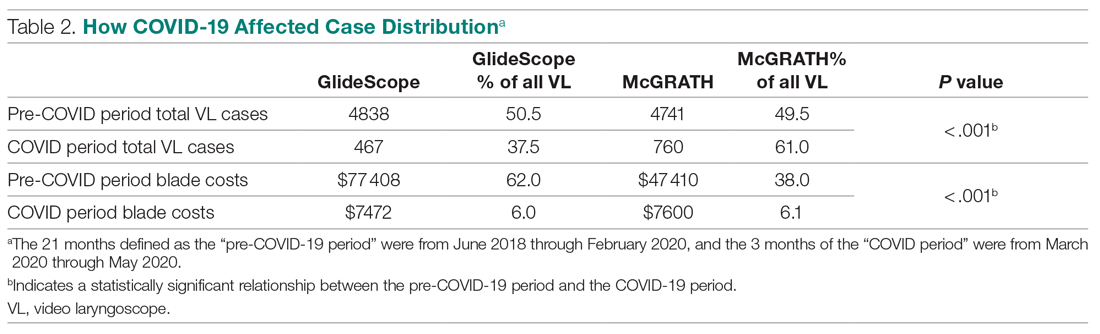

An analysis was performed to determine whether costs differed between those 2 instruments during the COVID-19 period. There was a statistically significant (P < .001) difference in the case distribution between use of the McGRATH and GlideScope VLs during that period. The calculated blade cost difference for the COVID period was $128 higher for the McGRATH even though 293 more intubations were performed with that device (Table 2).

Discussion

We attempted to provide useful cost estimates by presenting pricing data reflecting the approximate cost that most large institutional anesthesia practices would incur for using those 2 specific devices and related peripherals. The main findings of our analysis showed that use of the McGRATH MAC VL resulted in a 55% cost savings compared to the GlideScope, with a similar number of cases performed with each device over the 24-month study period. We believe this represents a substantial savings to the department and institution, which has prompted internal review on the use of video laryngoscopy equipment. None of the McGRATH units failed; however, the GlideScope required 3 baton replacements.