Delivery room planning

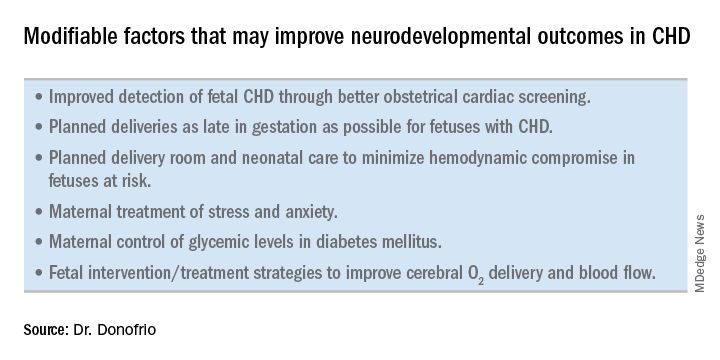

Ideally, our goal is to find ways of changing the circulation in utero to improve cerebral oxygenation and blood flow, and, consequently, improve brain development and long-term neurocognitive function. Despite significant efforts in this area, we’re not there yet.

Examples of strategies that are being tested include catheter intervention to open the aortic valve in utero for fetuses with critical aortic stenosis. This procedure currently is being performed to try to prevent progression of the valve abnormality to HLHS, but it has not been determined whether the intervention affects cerebral blood flow. Maternal oxygen therapy has been shown to change cerebral blood flow in the short term for fetuses with HLHS, but its long-term use has not been studied. At the time of birth, to prevent injury in the potentially more fragile brain of the newborn with CHD, what we can do is to identify those fetuses who are more likely to be at risk for hypoxia low cardiac output and hemodynamic compromise in the delivery room, and plan for specialized delivery room and perinatal management beyond standard neonatal care.

At Children’s National in 2004 we developed a risk stratification protocol to predict transitional and perinatal “levels of care” in which we prospectively determine, based on specific fetal echocardiographic findings, the likelihood of hemodynamic instability in the delivery room and the need for specialty care in the delivery room and in the first days and weeks of life.Most newborns with CHD are assigned to Level 1; they have no predicted risk of compromise in the delivery room – or even in the first couple weeks of life – and can deliver at a local hospital with neonatal evaluation and then consult with the pediatric cardiologist. Defects include shunt lesions such as septal defects or mild valve abnormalities.

Patients assigned to Level 2 have minimal risk of compromise in the delivery room but are expected to require postnatal surgery, cardiac catheterization, or another procedure before going home. They can be stabilized by the neonatologist, usually with initiation of a prostaglandin infusion, before transfer to the cardiac center for the planned intervention. Defects include single ventricle CHD and severe Tetralogy of Fallot.

Fetuses assigned to Level 3 and Level 4 are expected to have hemodynamic instability at cord clamping, requiring immediate specialty care in the delivery room that is likely to include urgent cardiac catheterization or surgical intervention. These defects are rare and include diagnoses such as transposition of the great arteries, HLHS with a restrictive or closed foramen ovale, and CHD with associated heart failure and hydrops.

We have found that fetal echocardiography accurately predicts postnatal risk and the need for specialized delivery room care in newborns diagnosed in utero with CHD and that level-of-care protocols ensure safe delivery and optimize fetal outcomes (J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1339-49; Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:737-47).

Such delivery planning, which is coordinated between obstetric, neonatal, cardiology, and surgical services with specialty teams as needed (for example, cardiac intensive care, interventional cardiology, and cardiac surgery), is recommended in a 2014 AHA statement on the diagnosis and treatment of fetal cardiac disease. In recent years it has become the standard of care in many health systems (Circulation. 2014;129[21]:2183-242).

The effect of maternal stress on the in utero environment is also getting increased attention in pediatric cardiology. Alterations in neurocognitive development and fetal and child cardiovascular health are likely to be associated with maternal stress during pregnancy, and studies have shown that maternal stress is high with prenatal diagnoses of CHD. We have to ask: Is stress a modifiable risk factor? There must be ways in which we can do better with prenatal counseling and support after a fetal diagnosis of CHD.

Screening for CHD

Initiating strategies to improve neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with CHD rests partly on identifying babies with CHD before birth through improved fetal cardiac screening. Research cited in the 2014 AHA statement indicates that nearly all women giving birth to babies with CHD in the United States have obstetric ultrasound examinations in the second or third trimesters, but that only about 30% of the fetuses are diagnosed prenatally.

Routine obstetric scanning should include assessment of not only a four-chamber view of the heart but also the outflow tracts and the three-vessel and trachea view. Ideally, as advised by the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, it should include a sweep of the heart from bottom to top and left to right with a view of both ventricular outflow tracts and the three-vessel view, with attention paid to machine settings to maximize image quality.Current indications for referral for a fetal echocardiogram – in addition to suspicion of a structural heart abnormality on obstetric ultrasound – include maternal factors, such as diabetes mellitus, that raise the risk of CHD above the baseline population risk for low-risk pregnancies.

Women with pregestational diabetes mellitus have a nearly fivefold increase in CHD, compared with the general population (3%-5%), and should be referred for fetal echocardiography. Women with gestational diabetes mellitus have no or minimally increased risk for fetal CHD, but it has been shown that there is an increased risk for cardiac hypertrophy – particularly late in gestation – if glycemic levels are poorly controlled. The 2014 AHA guidelines recommend that fetal echocardiographic evaluation be considered in those who have HbA1c levels greater than 6% in the second half of pregnancy.

Dr. Mary T. Donofrio is a pediatric cardiologist and director of the fetal heart program and critical care delivery program at Children’s National Medical Center, Washington. She reported that she has no disclosures relevant to this article.