Clinicians always should consider endometriosis in the diagnostic work-up of an infertility patient. But the diagnosis of endometriosis is often difficult, and management is complex. In this Update, we summarize international consensus documents on endometriosis with the aim of enhancing clinicians’ ability to make evidence-based decisions. In addition, we explore the interesting results of a large hysterosalpingography trial in which 2 different contrast mediums were used. Finally, we urge all clinicians to adapt the new standardized lexicon of infertility and fertility care terms that comprise the recently revised international glossary.

Endometriosis and infertility: The knowns and unknowns

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L, Adamson GD, et al; World Endometriosis Society Sao Paulo Consortium. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(2):315-324.

Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium. Consensus on current management of endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(6):1552-1568.

Rogers PA, Adamson GD, Al-Jefout M, et al; WES/WERF Consortium for Research Priorities in Endometriosis. Research priorities for endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(2):202-226.

Endometriosis is defined as "a disease characterized by the presence of endometrium-like epithelium and stroma outside the endometrium and myometrium. Intrapelvic endometriosis can be located superficially on the peritoneum (peritoneal endometriosis), can extend 5 mm or more beneath the peritoneum (deep endometriosis) or can be present as an ovarian endometriotic cyst (endometrioma)."1 Always consider endometriosis in the infertile patient.

Although many professional societies and numerous Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews have provided guidelines on endometriosis, controversy and uncertainty remain. The World Endometriosis Society (WES) and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF), however, have now published several consensus documents that assess the global literature and professional organization guidelines in a structured, consensus-driven process.2-4 These WES and WERF documents consolidate known information and can be used to inform the clinician in making evidence-linked diagnostic and treatment decisions. Recommendations offered in this discussion are based on those documents.

Establishing the diagnosis can be difficult

Diagnosis of endometriosis is often difficult and is delayed an average of 7 years from onset of symptoms. These include severe dysmenorrhea, deep dyspareunia, chronic pelvic pain, ovulation pain, cyclical or perimenstrual symptoms (bowel or bladder associated) with or without abnormal bleeding, chronic fatigue, and infertility. A major difficulty is that the predictive value of any one symptom or set of symptoms remains uncertain, as each of these symptoms can have other causes, and a significant proportion of affected women are asymptomatic.

For a definitive diagnosis of endometriosis, visual inspection of the pelvis at laparoscopy is the gold standard investigation, unless disease is visible in the vagina or elsewhere. Positive histology confirms the diagnosis of endometriosis; negative histology does not exclude it. Whether histology should be obtained if peritoneal disease alone is present is controversial: visual inspection usually is adequate, but histologic confirmation of at least one lesion is ideal. In cases of ovarian endometrioma (>4 cm in diameter) and in deeply infiltrating disease, histology should be obtained to identify endometriosis and to exclude rare instances of malignancy.

Compared with laparoscopy, transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) has no value in diagnosing peritoneal endometriosis, but it is a useful tool for both making and excluding the diagnosis of an ovarian endometrioma. TVUS may have a role in the diagnosis of disease involving the bladder or rectum.

At present, evidence is insufficient to indicate that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful for diagnosing or excluding endometriosis compared with laparoscopy. MRI should be reserved for when ultrasound results are equivocal in cases of rectovaginal or bladder endometriosis.

Serum cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) levels may be elevated in endometriosis. However, measuring serum CA 125 levels has no value as a diagnostic tool.

No fertility benefit with ovarian suppression

More than 2 dozen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide strong evidence that there is no fertility benefit from ovarian suppression. The drug costs and delayed time to pregnancy mean that ovarian suppression with oral contraceptives, other progestational agents, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists before fertility treatment is not indicated, with the possible exception of using it prior to in vitro fertilization (IVF).

Ovarian suppression also has been suggested as beneficial in conjunction with surgery. However, at least 16 RCTs have failed to show fertility improvement when ovarian suppression is given either preoperatively or postoperatively. Again, the delay in attempting pregnancy, drug costs, and adverse effects render ovarian suppression not appropriate.

While ovarian suppression has not been shown to increase pregnancy rates, ovarian stimulation (OS) likely does, especially when combined with intrauterine insemination (IUI).5

Laparoscopy: Appropriate for selected patients

A major decision for clinicians and patients dealing with infertility is whether to perform a laparoscopy, both for diagnostic and for treatment reasons. Currently, data are insufficient to recommend laparoscopic surgery prior to OS/IUI unless there is a history of evidence of anatomic disease and/or the patient has sufficient pain to justify the physical, emotional, financial, and time costs of laparoscopy. Laparoscopy therefore can be considered as possibly appropriate in younger women (<37 years of age) with short duration of infertility (<4 years), normal male factor, normal or treatable uterus, normal or treatable ovulation disorder, and limited prior treatment.

It is important to consider what disease might be found and how much of an increase in fertility can be obtained by treatment, so that the number needed to treat (NNT) can be used as an estimate of the potential value of laparoscopy in a given patient. A patient also should have no contraindications to laparoscopy and accept 9 to 15 months of attempting pregnancy before undergoing IVF treatment.

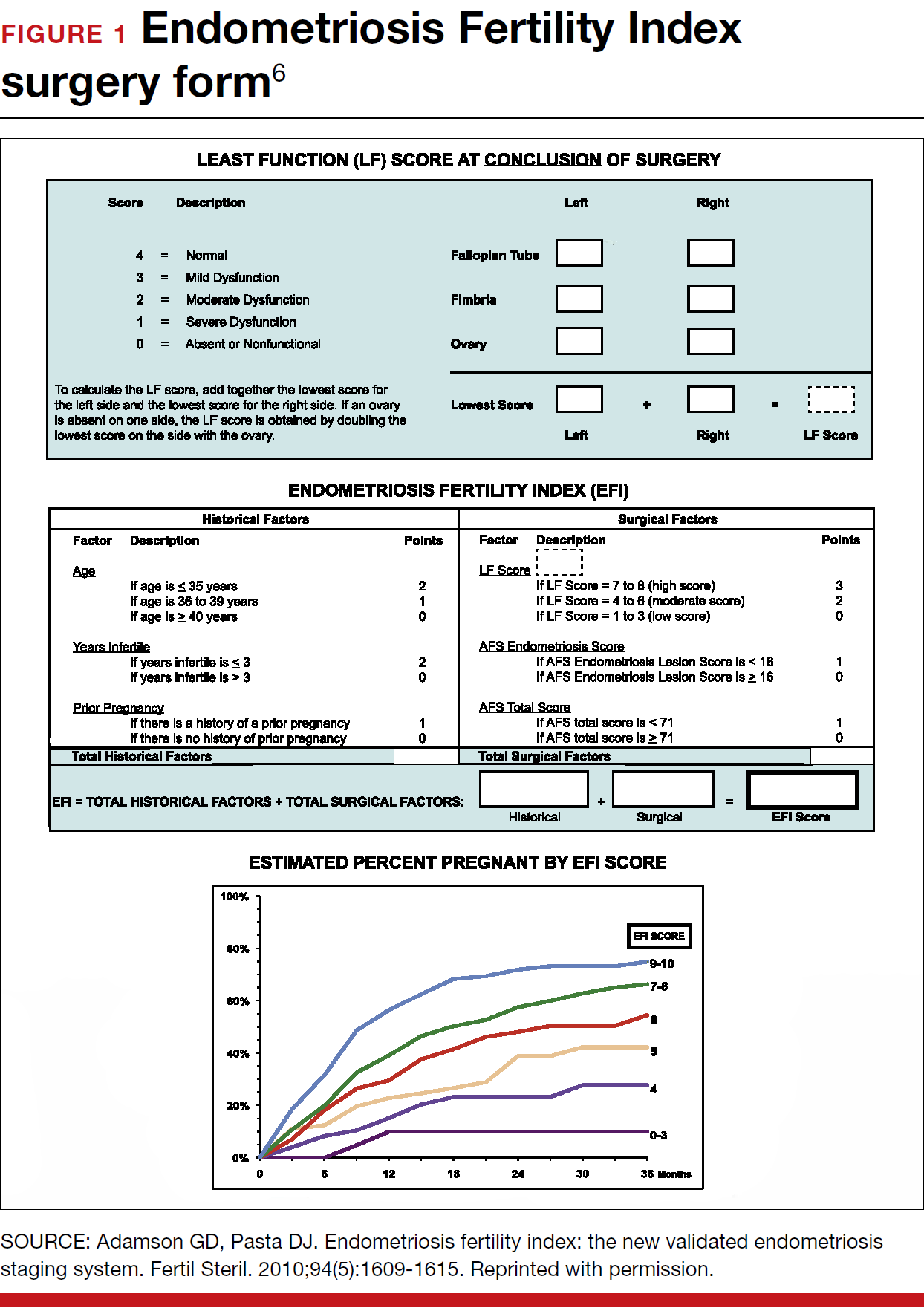

When laparoscopy is performed for minimal to mild disease, the odds ratio for pregnancy is 1.66 with treatment. It is important to remove all visible disease without injuring healthy tissue. When disease is moderate to severe, there is often severe anatomic distortion and a very low background pregnancy rate. Numerous uncontrolled trials show benefit of operative laparoscopy, especially for invasive, adhesive, and cystic endometriosis. However, repeat surgery is rarely indicated. After surgery, the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI) can be used to determine prognosis and plan management (FIGURE 1).6 An easy-to-use electronic EFI calculator is available online at www.endometriosisefi.com.

Management of endometriomas

Endometriomas are often operated on because of pain. Initial pain relief occurs in 60% to 100% of patients, but cysts recur following stripping about 10% of the time, and drainage without stripping, about 20%. With recurrence, pain is present about 75% of the time.

Pregnancy rates following endometrioma treatment depend on patient age and the status of the pelvis following operative intervention. This can be determined from the EFI. Often, the dilemma with endometriomas is how aggressive to be in removing them. The principles involved are to remove all the cyst wall if possible, but absolutely to minimize ovarian tissue damage, because reduced ovarian reserve is a possible major negative consequence of ovarian surgery.

Recommendations

While endometriosis is often a cause of infertility, often infertile patients do not have endometriosis. A careful history, physical examination, and ultrasonography, and possibly other imaging studies, are prerequisites to careful clinical judgment in diagnosing and treating infertile patients who might or do have endometriosis.

When pelvic pain is present, initially nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral contraceptives (OCs), progestational agents, or an intrauterine device can be helpful. These ovarian suppression medications do not increase fertility, however, and should be stopped in any patient who desires to get pregnant.

When pelvic and male fertility factors appear reasonably normal (even if minimal or mild endometriosis is suspected), treatment with clomiphene 100 mg on cycle days 3 through 7 and IUI for 3 to 6 cycles is an effective first step. However, if the patient has persistent pain and/or infertility without other significant infertility factors, then diagnostic laparoscopy with intraoperative treatment of disease is indicated.

Surgery well performed is effective treatment for all stages of endometriosis and endometriomas, both for infertility and for pain. Repeat surgery, however, is rarely indicated because of limited results, so it is important to obtain the best possible result on the first surgery. Surgery is indicated for large endometriomas (>4 cm). Endometriosis has almost no effect on the IVF live birth rate unless ovarian reserve has been reduced by endometriomas or surgery, so endometriosis surgery should be performed by skilled and experienced surgeons.

Endometriosis is a complex disease that can cause infertility. Its diagnosis and management are frequently difficult, requiring knowledge, experience, and good medical judgment and surgical skills. However, if evidence-linked principles are followed, effective treatment plans and good outcomes can be obtained for most patients.

Read about why oil-based contrast may be better than water-based contrast with HSG.