From the Editor

Why is breast density a weighty matter?

What will you tell your patient who asks about the clinical significance of dense breasts detected on her mammogram? Here I offer my current...

Wendie A. Berg, MD, PhD; JoAnn Pushkin; and Cindy Henke-Sarmento

Dr. Berg is Professor of Radiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Magee-Womens Hospital of UPMC, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Chief Scientific Advisor, DenseBreast-info.org.

Ms. Pushkin is Executive Director, DenseBreast-info, Inc.

Ms. Henke-Sarmento is Technology Director, DenseBreast-info, Inc.

Ms. Pushkin and Ms. Henke-Sarmento report that the 501(c)(3) nonprofit, DenseBreast-info, Inc., which supports the Web site DenseBreast-info.org, has received unrestricted educational grants from GE Healthcare and Volpara Solutions Ltd. Dr. Berg reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

There are several reasons that dense tissue increases risk. First, the glands tend to be made up of relatively actively dividing cells that can mutate and become cancerous (the more glandular tissue present, the greater the risk). Second, the local environment around the glands may produce certain growth hormones that stimulate cells to divide, and this seems to occur more in fibrous tissue than in fatty tissue.

Most women have breast density somewhere in the middle range, with their risk for breast cancer falling in between those with extremely dense breasts and those with fatty breasts.6 The risk for developing breast cancer is influenced by a combination of many different factors, including age, family history of cancer (particularly breast or ovarian cancer), and prior atypical breast biopsies. There currently is no reliable way to fully account for the interplay of breast density, family history, prior biopsy results, and other factors in determining overall risk. Importantly, more than half of all women who develop breast cancer have no known risk factors other than being female and aging.

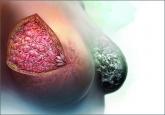

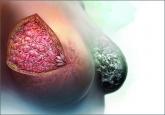

We’re all familiar with the adage that a picture is worth a thousand words. While the medical support personnel in your office are likely quite familiar with imaging reports and the terminology used in describing dense breasts, they may be quite unfamiliar with what a fatty versus dense breast actually looks like on a mammogram, and how cancer may display in each. Illustrated examples, as seen here, are useful for reference.

In the fatty breast (A), a small cancer (arrow) is seen easily. In a breast categorized as scattered fibroglandular density (B), a large cancer is easily seen (arrow) in the relatively fatty portion of the breast, though a small cancer could have been hidden in areas with normal glandular tissue.

In a breast categorized as heterogeneously dense (C), a 4-cm (about 1.5-inch) cancer (arrows) is hidden by the dense breast tissue. This cancer also has spread to a lymph node under the arm (curved arrow).

In an extremely dense breast (D), a cancer is seen because part of it is located in the back of the breast where there is a small amount of dark fat making it easier to see (arrow and triangle marker indicating lump). If this cancer had been located near the nipple and completely surrounded by white (dense) tissue, it probably would not have been seen on mammography.

Image: Courtesy of Dr. Regina Hooley and DenseBreast-info.org

Are screening mammography outcomes different for women with dense versus fatty breasts?

Yes. Cancer is more likely to be clinically detected in the interval between mammography screens (defined as interval cancer) in women with dense breasts. Such interval cancers tend to be more aggressive and have worse outcomes. Compared with those in fatty breasts, cancers found in dense breasts more often7:

Does supplemental screening beyond mammography save lives?

Mammography is the only imaging screening modality that has been studied by multiple randomized controlled trials with mortality as an endpoint. Across those trials, mammography has been shown to reduce deaths due to breast cancer. The randomized trials that show a benefit from mammography are those in which mammography increased detection of invasive breast cancers before they spread to lymph nodes.8

No randomized controlled trial has yet been reported on any other imaging screening modality, but it is expected that other screening tests that increase detection of node-negative invasive breast cancers beyond mammography should further reduce breast cancer mortality.

Proving the mortality benefit of any supplemental screening modality would require a very large, very expensive randomized controlled trial with 15 to 20 years of follow-up. Given the speed of technologic developments, any results likely would be obsolete by the trial’s conclusion. What we do know is that women at high risk for breast cancer who undergo annual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening are less likely to have advanced breast cancer than their counterparts who were not screened with MRI.9

We also know that average-risk women who are screened with ultrasonography in addition to mammography are unlikely to have palpable cancer in the interval between screens,10,11 with the rates of such interval cancers similar to women with fatty breasts screened only with mammography. The cancers found only on MRI or ultrasound are mostly small invasive cancers (average size, approximately 1 cm) that are mostly node negative.12,13 MRI also finds some ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

What will you tell your patient who asks about the clinical significance of dense breasts detected on her mammogram? Here I offer my current...

The benefit is small and the cost is high, according to this comparative modeling study.

The authors of this prospective study involving more than 350,000 patients observed high interval cancer rates for women with 5-year breast cancer...