4 approaches to managing intraoperative blood loss

In my practice, we employ misoprostol, tranexamic acid, vasopressin, and a uterine and ovarian vessel tourniquet to manage intraoperative blood loss.12 Although no data exist to show that using these methods together is advantageous, they have different mechanisms of action and no negative interactions.

Misoprostol 400 μg inserted vaginally 2 hours before surgery induces myometrial contraction and compression of the uterine vessels. This agent can reduce blood loss by 98 mL per case.12

Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic, is given IV piggyback at the start of surgery at a dose of 10 mg/kg; it can reduce blood loss by 243 mL per case.12

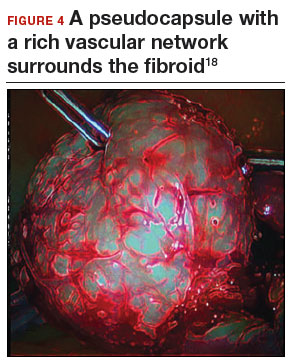

Vasopressin 20 U in 100 mL normal saline, injected below the vascular pseudocapsule, causes vasoconstriction of capillaries and small arterioles and venules and can reduce blood loss by 246 mL per case.12 Intravascular injection should be avoided because rare cases of bradycardia and cardiovascular collapse have been reported.13 Using vasopressin to decrease blood loss during myomectomy is an off-label use of this drug.

Place a tourniquet around the lower uterine segment, including the infundibular pelvic ligaments. Tourniquet use is the most effective way to decrease blood loss during myomectomy, since it can reduce blood loss by 1,870 mL.12 For women who wish to preserve fertility, take care to ensure that the tourniquet does not compromise the tubes. For women who are certain they do not want to preserve fertility, discuss the possibility of performing bilateral salpingectomy to decrease the risk of subsequent tubal (“ovarian”) cancer.

Some surgeons incise the broad ligaments bilaterally and pass the tourniquet through the broad ligaments to avoid compromising blood flow to the ovaries. Occluding the utero- ovarian ligaments with bulldog clamps to control collateral blood flow from the ovarian artery has been described, but the clamps can tear these often enlarged and fragile uterine veins during manipulation of the uterus. Release the tourniquet every 15 to 30 minutes to allow reperfusion of the ovaries. In women with ovarian torsion lasting hours to days, the ovary has been found to resist hypoxia and recover function.14 Antral follicle counts of detorsed and contralateral normal ovaries following a mean of 13 hours of hypoxia are similar 3 months following detorsion.15

Consider blood salvage. For women with multiple or very large fibroids, consider using a salvage-type autologous blood transfusion device, which has been shown to reduce the need for heterologous blood transfusion.16 This device suctions blood from the operative field, mixes it with heparinized saline, and stores the blood in a canister (FIGURE 2). If the patient requires blood reinfusion, the stored blood is washed with saline, filtered, centrifuged, and given back to the patient intravenously. Blood salvage, or cell salvage, avoids the risks of infection and transfusion reaction, and the oxygen transport capacity of salvaged red blood cells is equal to or better than that of stored allogeneic red cells.

Additional surgical considerations

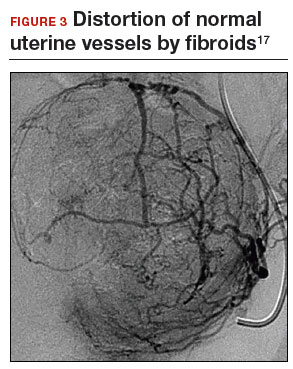

Previous teaching suggested that proper placement of the uterine incisions was an important factor in limiting blood loss. Some authors suggested that vertical uterine incisions would avoid injury to the ascending uterine vessels should inadvertent extension of the incision occur. Other authors proposed horizontal uterine incisions to avoid severing the arcuate vessels that branch off from the ascending uterine arteries and run transversely across the uterus. However, since fibroids distort the normal vascular architecture, it is not possible to entirely avoid severing vessels in the myometrium (FIGURE 3).17 Uterine incisions can therefore be made as needed based on the position of the fibroids and the need to avoid inadvertent extension to the ascending uterine vessels or cornua.17

Fibroid anatomy and vascularity. Fibroids are entirely encased within the dense blood supply of a pseudocapsule (FIGURE 4),18 and no distinct “vascular pedicle” exists at the base of the fibroid.19 It is therefore important to extend the uterine incisions down through the entire pseudocapsule until the fibroid is clearly visible. This will identify a less vascular surgical plane, which is deeper than commonly recognized. Once the fibroid is reached, the pseudocapsule can be “wiped away” using a dry laparotomy sponge (see VIDEO 3). Staying under the pseudocapsule reduces bleeding and may preserve the tissue growth factors and neurotransmitters that are thought to promote wound healing.20

Adhesion prevention. Limiting the number of uterine incisions has been suggested as a way to reduce the risk of postoperative pelvic adhesions. To extract fibroids that are distant from an incision, however, tunnels must be created within the myometrium, and this makes hemostasis within these defects difficult. In that blood increases the risk of adhesion formation, tunneling may be counterproductive. If tunneling incisions are avoided and hemostasis is secured immediately, the risk of adhesion formation should be lessened.

Therefore, make incisions directly over the fibroids. Remove only easily accessed fibroids and promptly close the defects to secure hemostasis. Multiple uterine incisions may be needed; adhesion barriers may help limit adhesion formation.21

On final removal of the tourniquet, carefully inspect for bleeding and perform any necessary re-suturing. We place a pain pump (ON-Q* Pain Relief System, Halyard Health, Inc) for pain management and close the abdominal incision in the standard manner.