What is the risk of untreated illness during pregnancy?

During pregnancy, women are treated for many medical disorders, including psychiatric illness. One general guideline is that, if a pregnant woman does not need a medication—whether it be for an allergy, hypertension, or another disorder—she should not take it. Conversely, if a medication is required for a patient’s well-being, her physician should continue it or switch to a safer one. This general guideline is the same for women with depression, anxiety, or a psychotic disorder.

Managing hypertension during pregnancy is an example of choosing treatment when the risk of the illness to the mother and the infant outweighs the likely small risk associated with taking a medication. Blood pressure is monitored, and, when it reaches a threshold, an antihypertensive is started promptly to avoid morbidity and mortality.

Psychiatric illness carries risks for both mother and fetus as well, but no data show a clear threshold for initiating pharmacologic treatment. Therefore, in prescribing medication the most important steps are to take a complete history and perform a thorough evaluation. Important information includes the number and severity of previous episodes, prior history of hospitalization or suicidal thoughts or attempts, and any history of psychotic or manic status.

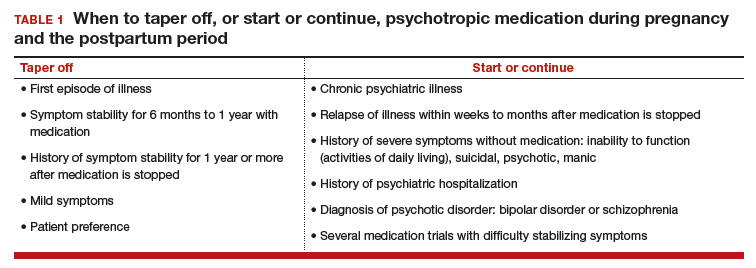

Whether to continue or discontinue medication is often decided after inquiring about other times a medication was discontinued. A patient who in the past stayed well for several years after stopping a medication may be able to taper off a medication and conceive during a window of wellness. Some women who have experienced only one episode of illness and have been stable for at least a year may be able to taper off a medication before conceiving (TABLE 1).

In the risk–benefit analysis, assess the need for pharmacologic treatment by considering the risk that untreated illness poses for both mother and fetus, the benefits of treatment for both, and the risk of medication exposure for the fetus.4

Mother: Risk of untreated illness versus benefit of treatment

A complete history and a current symptom evaluation are needed to assess the risk that nonpharmacologic treatment poses for the mother. Women with functional impairment, including inability to work, to perform activities of daily living, or to take care of other children, likely require treatment. Studies have found that women who discontinue treatment for a psychiatric illness around the time of conception are likely to experience a recurrence of illness during pregnancy, often in the first trimester, and must restart medication.5,6 For some diagnoses, particularly bipolar disorder, symptoms during a relapse can be more severe and more difficult to treat, and they carry a risk for both mother and fetus.7 A longitudinal study of pregnant women who stopped medication for bipolar disorder found a 71% rate of relapse.7 In cases in which there is a history of hospitalization, suicide attempt, or psychosis, discontinuing treatment is not an option; instead, the physician must determine which medication is safest for the particular patient.

Related article:

Does PTSD during pregnancy increase the likelihood of preterm birth?

Fetus: Risk of untreated illness versus benefit of treatment

Mothers with untreated psychiatric illness are at higher risk for poor prenatal care, substance abuse, and inadequate nutrition, all of which increase the risk of negative obstetric and neonatal outcomes.8 Evidence indicates that untreated maternal depression increases the risk of preterm delivery and low birth weight.9 Children born to mothers with depression have more behavioral problems, more psychiatric illness, more visits to pediatricians, lower IQ scores, and attachment issues.10 Some of the long-term negative effects of intrauterine stress, which include hypertension, coronary heart disease, and autoimmune disorders, persist into adulthood.11

Fetus: Risk of medication exposure

With any pharmacologic treatment, the timing of fetal exposure affects resultant risks and therefore must be considered in the management plan.

Before conception. Is there any effect on ovulation or fertilization?

Implantation. Does the exposure impair the blastocyst’s ability to implant in the uterine lining?

First trimester. This is the period of organogenesis. Regardless of drug exposure, there is a 2% to 4% baseline risk of a major malformation during any pregnancy. The risk of a particular malformation must be weighed against this baseline risk.

According to limited data, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may increase the risk of early miscarriage.12 SSRIs also have been implicated in increasing the risk of cardiovascular malformations, although the data are conflicting.13,14

Antiepileptics such as valproate and carbamazepine are used as mood stabilizers in the treatment of bipolar disorder.15 Extensive data have shown an association with teratogenicity. Pregnant women who require either of these medications also should be prescribed folic acid 4 or 5 mg/day. Given the high risk of birth defects and cognitive delay, valproate no longer is recommended for women of reproductive potential.16

Lithium, one of the safest medications used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, is associated with a very small risk of Ebstein anomaly.17

Lamotrigine is used to treat bipolar depression and appears to have a good safety profile, along with a possible small increased risk of oral clefts.18,19

Atypical antipsychotics (such as aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone) are often used first-line in the treatment of psychotic disorders and bipolar disorder in women who are not pregnant. Although the safety data on use of these drugs during pregnancy are limited, a recent analysis of pregnant Medicaid enrollees found no increased risk of birth defects after controlling for potential confounding factors.20 Common practice is to avoid these newer agents, given their limited data and the time needed for rare malformations to emerge (adequate numbers require many exposures during pregnancy).