Breast cancer

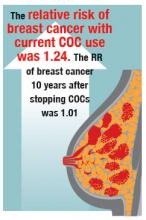

The relationship between COC use and breast cancer is controversial. However, most oncologists believe that current use of COCs may be associated with a small increase in the risk of breast cancer diagnosis. The risk is attenuated after discontinuing COC use. In an individual data meta-analysis of 54 epidemiologicalstudies including 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 without it, the RR of breast cancer with current COC use was 1.24 (95% CI, 1.15–1.33; P<.0001). The RR of breast cancer 10 years after stopping COCs was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.96–1.05; NS).6In the prospective NHS study of 116,608 nurses with 1,246,967 years of follow-up, the multivariate relative risk (mRR) of breast cancer with current COC use was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.03–1.73). Past use of COCs was not associated with a significantly increased risk of breast cancer (mRR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.95–1.33; NS).7

In the RCGPOC study (approximately 46,000 women), current use of COCs was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 1.48; 95% CI,1.10–1.97). Five to 15 years after stopping COCs, there was no significant association between prior COC use and breast cancer (IRR, 1.12; 99% CI, 0.91–1.39; NS).2

Related article:

Webcast: Oral contraceptives and breast cancer: What’s the risk?

It is important to note that it is not possible to conclude from these data whether the reported association between current use of COCs and breast cancer is due to early and accelerated diagnosis of breast cancer, the biological effects of hormones contained in COCs on breast tissue and nascent tumors, or both. In addition, formulations of COCs prescribed in the 1960s and 1970s contained higher doses of estrogen, raising the possibility that the association between COCs and breast cancer is due to COC formulations that are no longer prescribed. However, in animal models and postmenopausal women certain combinations of estrogen plus progestin clearly influence breast cancer biology and cancer risk.8,9

Women carrying BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, which increase the risk of ovarian and breast cancer, are often counseled to consider bilateral salpingectomy between age 35 and 40 years to reduce the risk of developing ovarian cancer. An important clinical question is what is the impact of combination estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives (COC) use on ovarian and breast cancer risk among these women?

Meta-analyses of the association between COC use and ovarian cancer consistently report that COC use reduces the risk of ovarian cancer in women with clinically important BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations.1,2 For example, a meta-analysis of 6 studies reported that women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations who used COCs had a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer (odds ratio [OR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.46–0.73).1

The association between COC use and breast cancer risk is not clear. One meta-analysis reported no significant association between COC use and breast cancer risk among BRCA mutation carriers (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.93–1.58).1 Another meta-analysis reported a significant association between COC use before 1975 and breast cancer risk (RR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.06–2.04) but not with recent low-estrogen formulations of COC (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.74–1.86).2

Based on the available data, the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommends that women with clinically significant BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations be offered chemoprevention with COCs because the benefit of ovarian cancer risk reduction outweighs the possible impact on breast cancer risk.3 A contrarian view-point espoused by some oncologists is that since women with BRCA mutations should have their ovaries removed prior to getting ovarian cancer, the clinical utility of recommending COC chemoprevention of ovarian cancer is largely irrelevant.

References

- Moorman PG, Havrilesky LJ, Gierisch JM, et al. Oral contraceptives and risk of ovarian cancer and breast cancer among high-risk women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4188–4198.

- Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Canc. 2010;46(12):2275–2284.

- Walker JL, Powell CB, Chen LM, et al. Society of Gynecologic Oncology recommendations for the prevention of ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(13):2108–2120.

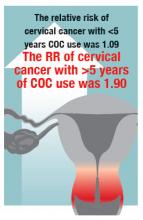

Cervical cancer

Prolonged COC use is associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. The risk is no longer observed 10 years after stopping COC use. In an individual data meta-analysis of 24 epidemiological studies including 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without it, the relative risk of cervical cancer with less than 5 years or 5 or more years of COC use was 1.09 and 1.90, respectively. Analyses of potential confounding exposures, including age at first sexual intercourse, condom use, cigarette smoking, and number of sexual partners, did not significantly weaken the observed association between cervical cancer and COC use of 5 or more years.10 In a study of women who were positive for HPV DNA, the odds ratio for cervical cancer among women who had used COCs11:- less than 5 years, 0.73 (95% CI, 0.52–1.03)

- 5 to 9 years, 2.82 (95% CI, 1.46–5.42)

- ≥10 years, 4.03 (95% CI, 2.09–8.02).

It is not possible to conclude from these data whether the association between COC use and cervical cancer is due to the biological effects of hormones on the initiation and progression of HPV disease or confounding factors that have yet to be identified. It is known that estrogens and progestins influence the immune defense system of the lower genital tract, and this may be a pathway that influences the acquisition and progression of viral disease.12 From a clinical perspective, cervical cancer is largely preventable with HPV vaccination and screening. Therefore, the risk between COC use and cervical cancer is likely limited to women who have not been vaccinated and who are not actively participating in cervical cancer screening.

The bottom line

COC use markedly reduces the risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers, and slightly increases the risk of breast cancer. Prolonged COC use may be associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. Using available epidemiological data, investigators attempted to project the impact of these competing risks on the approximate 12,300,000 females who live in Australia. Based on the pattern of COC use and the cancer incidence in Australia in 2010, the investigators calculated that COC use would cause about 105 breast and 52 cervical cancers and prevent 1,032 endometrial and 308 ovarian cancers.13 This analysis indicates that the balance of risks and benefits related to COC use and cancer generally favors COC use.

Prevention of unintended pregnancy is a major public health goal. Many women choose COCs as their preferred approach to preventing unintended pregnancy. Evaluated from a whole-life perspective the health benefits of COCs are substantial and represent a great advance in women’s health.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.