About 3% to 4% of all fetuses at term are in breech presentation. Since 2000, when Hannah and colleagues reported finding that vaginal delivery of breech-presenting babies was riskier than cesarean delivery,1 most breech-presenting neonates in the United States have been delivered abdominally2—despite subsequent questioning of some of that study’s conclusions.

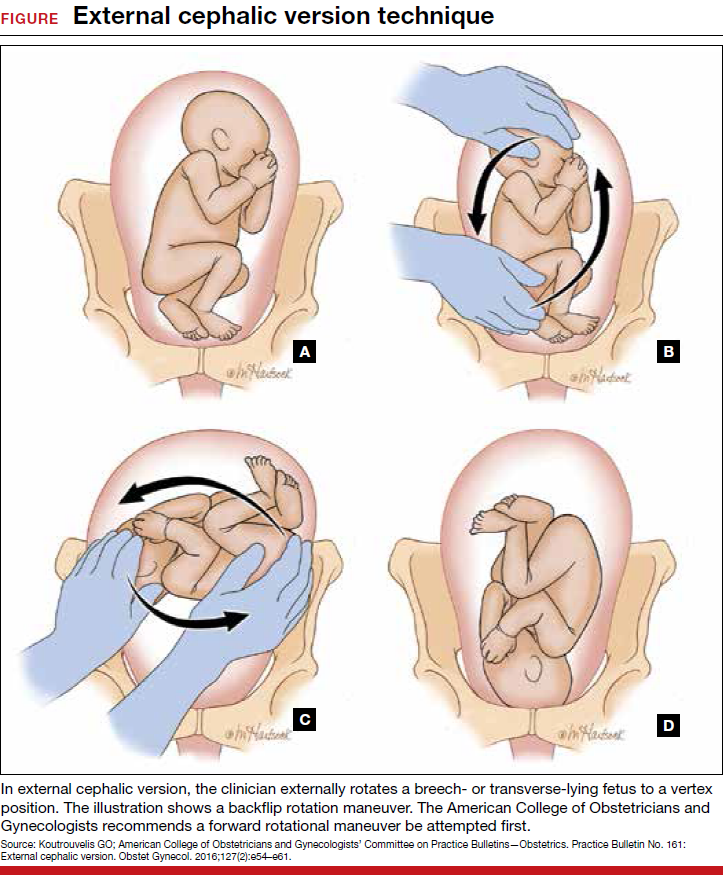

Each year in the United States, approximately 4 million babies are born, and fetal malpresentation accounts for 110,000 to 150,000 cesarean deliveries. In fact, about 15% of all cesarean deliveries in the United States are for breech presentation or transverse lie; in England the percentage is 10%.3 Fortunately, the repopularized technique of external cephalic version (ECV), in which the clinician externally rotates a breech- or transverse-lying fetus to a vertex position (FIGURE), along with the facilitating tools of tocolysis and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, is helping to reduce the number of breech presentations in fetuses at term and thus the number of cesarean deliveries and their sequelae—placenta accreta, prolonged recovery, and cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies.

Reluctance to perform ECV is unfounded

In the United States, the practice of offering ECV to women who present with their fetus in breech presentation at term varies tremendously. It is routine at some institutions but not even offered at others.

Many ObGyns are reluctant to perform ECV. Cited reasons include the potential for injury to the fetus and mother (and related liability concerns), the ease of elective cesarean delivery, the variable success rate of ECV (35% to 86%),4 and the pain that women often have with the procedure. According to the literature, however, these concerns either are unfounded or can be mitigated with use of current techniques. Multiple studies have found that the risk of ECV to the fetus and mother is minimal, and that tocolysis and neuraxial anesthesia can facilitate the success of ECV and relieve the pain associated with the procedure.

Related article:

2017 Update on obstetrics

Indications for ECV

The indications for ECV include breech, oblique, or transverse lie presentation after 36 weeks’ gestation and the mother’s desire to avoid cesarean delivery. A clinician skilled in ECV and a facility where emergency cesarean delivery is possible are essential.

There are several instances in which ECV should not be attempted.

Contraindications include:

- concerns about fetal status, including nonreactive nonstress test, biophysical profile score <6/8, severe intrauterine growth restriction, decreased end-diastolic umbilical blood flow

- placenta previa

- multifetal gestation before delivery of first twin

- severe oligohydramnios

- severe preeclampsia

- significant fetal anomaly

- known malformation of uterus

- breech with hyperextended head or arms above shoulders, as seen on ultrasonography.

More controversial contraindications include prior uterine incision, maternal obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2), ruptured membranes, and fetal macrosomia.

Read about timing, success rates, risk factors, alternate approaches for ECV