CASE Chronic pelvic pain from endometriosis

A 40-year-old woman (G0) has a 20-year history of chronic pelvic pain. Stage III endometriosis is diagnosed on laparoscopic excision of endometriotic tissue. Postoperative pain symptoms include dysmenorrhea and deep dyspareunia, and the patient is feeling anxious. Physical examination reveals a retroverted uterus, right adnexal fullness and tenderness, and tenderness on palpation of the right levator ani and right obturator internus; rectovaginal examination findings are unremarkable. The patient, though now engaged in a pelvic floor physical therapy program, has yet to achieve the pain control she desires. After reviewing the treatment strategies for endometriosis with the patient, she elects definitive surgical management with minimally invasive hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy. What pre-, intra-, and postoperative pain management plan do you devise for this patient?

Chronic pelvic pain presents a unique clinical challenge, as pain typically is multifactorial, and several peripheral pain generators may be involved. Although surgery can be performed to manage anatomically based disease processes, it does not address pain from musculoskeletal or neuropathic sources. A complete medical history and a physical examination are of utmost importance in developing a comprehensive multimodal management plan that may include surgery as treatment for the pain.

The standard of care for surgery is a minimally invasive approach (vaginal, laparoscopic, or robot-assisted laparoscopic), as it causes the least amount of trauma. Benefits of minimally invasive surgery include shorter hospitalization and faster recovery, likely owing to improved perioperative pain control, decreased blood loss, and fewer infections. Although this approach minimizes surgical trauma and thereby helps decrease the surgical stress response, the patient experience can be optimized with use of enhanced recovery pathways (ERPs), a multimodal approach to perioperative care.

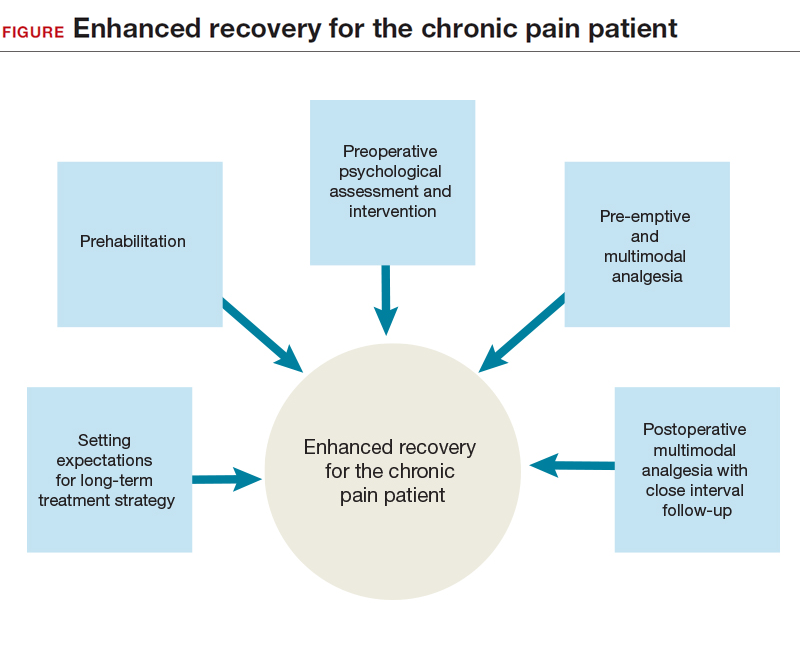

ERPs were initially proposed as a means of reducing the degree of surgical injury and the subsequent physiologic stress response.1 This multimodal approach begins in the outpatient setting, includes preoperative and intraoperative modalities, and continues postoperatively. In patients with chronic pain, ERPs are even more important. Assigning “prehabilitation” and setting expectations for surgery goals are the first step in improving the patient experience. Intraoperative use of opioid-sparing anesthetics or regional anesthesia can improve recovery. After surgery, patients with chronic pain and/or opioid dependence receive medications on a schedule, along with short-interval follow-up. Ultimately, reducing acute postoperative pain may lower the risk of developing chronic pain.

In this article on patients with chronic pelvic pain, we highlight elements of ERPs within the framework of enhanced recovery after surgery. Many of the interventions proposed here also can be used to improve the surgical experience of patients without chronic pain.

Preadmission education, expectations, and optimization

Preoperative counseling for elective procedures generally occurs in the outpatient setting. Although discussion traditionally has covered the type of procedure and its associated risks, benefits, and alternatives, new guidelines suggest a more mindful and comprehensive approach is warranted. Individualized patient-centered education programs have a positive impact on the perioperative course, effecting reductions in preoperative anxiety, opioid requirements, and hospital length of stay.2 From a pain management perspective, the clinician can take some time during preoperative counseling to inform the patient about the pain to be expected from surgery, the ways the pain will be managed intraoperatively and postoperatively, and the multimodal strategies that will be used throughout the patient’s stay2 and that may allow for early discharge. Although preadmission counseling still should address expectations for the surgery, it also presents an opportunity both to assess the patient’s ability to cope with the physical and psychological stress of surgery and to offer the patient appropriate need-based interventions, such as prehabilitation and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

Prehabilitation is the process of increasing functional capacity before surgery in order to mitigate the stress of the surgery. Prehabilitation may involve aerobic exercise, strength training, or functional task training. The gynecologic surgery literature lacks prehabilitation data, but data in the colorectal literature support use of a prehabilitation program for patients having a scheduled colectomy, with improved postoperative recovery.3 Although the colectomy cohort predominantly included older men, the principle that guides program implementation is the same: improve recovery after the stress of abdominal surgery. Indeed, a patient who opts for an elective surgery may have to wait several weeks before undergoing the procedure, and during this period behavioral interventions can take effect. With postoperative complications occurring more often in patients with reduced functional capacity, the data support using prehabilitation to decrease the incidence of postoperative complications, particularly among the most vulnerable patients.4 However, a definitive recommendation on use of pelvic floor exercises as an adjunct to prehabilitation cannot be made.4 Successful prehabilitation takes at least 4 weeks and should be part of a multimodal program that addresses other behavioral risk factors that may negatively affect recovery.5 For example, current tobacco users have compromised pulmonary status and wound healing immediately after surgery, and use more opioids.6 Conversely, smoking cessation for as little as 4 weeks before surgery is associated with fewer complications.7 In addition, given that alcohol abuse may compromise the surgical stress response and increase the risk of opioid misuse, addressing alcohol abuse preoperatively may improve postoperative recovery.8

Treating mood disorders that coexist with chronic pain disorders is an important part of outpatient multimodal management—psychological intervention is a useful adjunct to prehabilitation in reducing perioperative anxiety and improving postoperative functional capacity.9 For patients who have chronic pain and are undergoing surgery, it is important to address any anxiety, depression, or poor coping skills (eg, pain catastrophizing) to try to reduce the postoperative pain experience and decrease the risk of chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP).10,11

Before surgery, patients with chronic pain syndromes should be evaluated for emotional distress and pain coping ability. When possible, they should be referred to a pain psychologist, who can initiate CBT and other interventions. In addition, pain coping skills can be developed or reinforced to address preoperative anxiety and pain catastrophizing. These interventions, which may include use of visual imagery, breathing exercises, and other relaxation techniques, are applicable to the management of postoperative anxiety as well.

Read about preoperative multimodal analgesia and intra- and postoperative management.