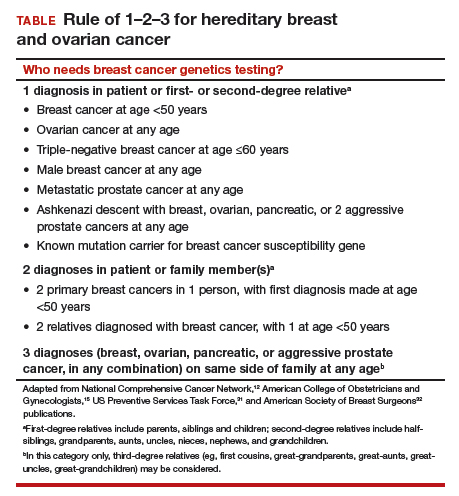

Guidelines for genetics referral and testing

According to the TABLE, which summarizes national guidelines for genetics referral, maternal and paternal family histories are equally important. Our patient was under age 50 at diagnosis, has a history of triple-negative breast cancer, is of Ashkenazi ancestry, and has a family history of metastatic prostate cancer. She meets the criteria for genetics testing, and screening for her daughters most certainly will depend on the findings of that testing. If she carries a BRCA1 mutation, as might be anticipated, each daughter would have a 50% chance of having inherited the mutation. If they carry the mutation as well, they would begin breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening at age 25.12 If they decide against genetics testing, they could still undergo MRI screening as untested first-degree relatives of a BRCA carrier, per ACS recommendations.13

Integrating evidence and experience

Over the past 10 to 20 years, other breast cancer susceptibility genes (eg, BRCA2, PALB2, CHEK2) have been identified. More recently, next-generation sequencing has become commercially available. Laboratories can use this newer method to sequence multiple genes rapidly and in parallel, and its cost is similar to that of single-syndrome testing.14 When more than 1 gene can explain an inherited cancer syndrome, multigene panel testing may be more efficient and cost-effective. Use of multigene panel testing is supported in guidelines issued by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network,12 the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,15 and other medical societies.

For our patient, the most logical strategy would be to test for the 3 mutations most common in the Ashkenazi population and then, if no mutation is found, perform multigene panel testing.

Formal genetics counseling can be very helpful for a patient, particularly in the era of multigene panel testing.16,17 A detailed pedigree (family tree) is elicited, and a genetics specialist determines whether testing is indicated and which test is best for the patient. Possible test findings are explained. The patient may be found to have a pathogenic variant with associated increased cancer risk, a negative test result (informative or uninformative), or a variant of uncertain significance (VUS). VUS is a gene mutation identified with an unknown effect on protein function and an unclear association with cancer risk. A finding of VUS may make the patient anxious,18 create uncertainty in the treating physician,19 and lead to harmful overtreatment, excessive surveillance, or unnecessary use of a preventive measure.19–21 Genetics counseling allows the patient, even the patient with VUS, to make appropriate decisions.22 Counseling may also help a patient or family process emotional responses, such as fear and guilt. In addition, counselors are familiar with relevant laws and regulations, such as the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA), which protects patients from insurance and employment discrimination. Many professional guidelines recommend providing genetics counseling in conjunction with genetics testing,12,23 and some insurance companies and some states require counseling for coverage of testing.

Cost of genetics counseling. If patients are concerned about the cost of genetics testing, they can be reassured with the following information24–26:

- The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) identifies BRCA testing as a preventive service

- Medicare provides coverage for affected patients with a qualifying personal history

- 97% of commercial insurers and most state Medicaid programs provide coverage for hereditary cancer testing

- Most commercial laboratories have affordability programs that may provide additional support.

If a BRCA mutation is found: Many patients question the value of knowing whether they have a BRCA mutation. What our patient, her daughters, and others may not realize is that, if a BRCA mutation is found, breast MRI screening can begin at age 25. Although contrast-enhanced MRI screening is highly sensitive in detecting breast cancer,27–29 it lacks specificity and commonly yields false positives.

Some patients also worry about overdiagnosis with this highly sensitive test. Many do not realize that preventively prescribed oral contraceptives can reduce the risk of ovarian cancer by 50%, and cosmetically acceptable risk-reducing breast surgeries can reduce the risk by 90%.

Many are unaware of the associated risks with ovarian, prostate, pancreatic, and other cancers; of risk management options; and of assisted reproduction options, such as preimplantation genetics diagnosis, which can prevent the passing of a genetic mutation to future generations. The guidelines on risk management options are increasingly clear and helpful,12,30–32 and women often turn to their ObGyns for advice about health and prevention.

ObGyns are often the first-line providers for women with a personal or family history of breast cancer. Identification of at-risk patients begins with taking a careful family history and becoming familiar with the rapidly evolving guidelines in this important field. Identification of appropriate candidates for breast cancer genetics testing is a key step toward prevention, value-based care, and avoidance of legal liability.

CASE Resolved

In this case, testing for the 3 common Ashkenazi BRCA founder mutations was negative, and multigene panel testing was also negative. Her husband is not of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and there is no significant family history of cancer on his side. The daughters are advised to begin high-risk screening at the age of 32, 10 years earlier than their mother was diagnosed, but no genetic testing is indicated for them.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.