The complex challenge of managing preeclampsia

Chronic hypertension is not the only risk factor for preeclampsia; others include nulliparity, history of preeclampsia, multifetal gestation, underlying renal disease, SLE, antiphospolipid syndrome, thyroid disease, and pregestational diabetes. Furthermore, preeclampsia has a bimodal age distribution, occurring more often in adolescent pregnancies and women of advanced maternal age. Risk is also increased in the presence of abnormal levels of various serum analytes or biochemical markers, such as a low level of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A or estriol or an elevated level of maternal serum α-fetoprotein, human chorionic gonadotropin, or inhibin—findings that might reflect abnormal placentation.9

In fact, the findings of most studies that have looked at the pathophysiology of preeclampsia appear to show that several noteworthy pathophysiologic changes are evident in early pregnancy10,11:

- incomplete trophoblastic invasion of spiral arteries

- retention of thick-walled, muscular arteries

- decreased placental perfusion

- early placental hypoxia

- placental release of factors that lead to endothelial dysfunction and endothelial damage.

Ultimately, vasoconstriction becomes evident, which leads to clinical manifestations of the disorder. In addition, there is an increase in the level of thromboxane (a vasoconstrictor and platelet aggregator), compared to the level of prostacyclin (a vasodilator).

ACOG revises nomenclature, provides recommendations

The considerable expansion of knowledge about preeclampsia over the past 10 to 15 years has not translated to better outcomes. In 2012, ACOG, in response to troubling observations about the condition (see “ACOG finds compelling motivation to boost understanding, management of preeclampsia,”), created a Task Force to investigate hypertension in pregnancy.

Findings and recommendations of the Task Force were published in November 2013,3 and have been endorsed and supported by professional organizations, including the American Academy of Neurology, American Society of Hypertension, Preeclampsia Foundation, and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. A major premise of the Task Force that has had a direct impact on recommendations for management of preeclampsia is that the condition is a progressive and dynamic process that involves multiple organ systems and is not specifically confined to the antepartum period.

The nomenclature of mild preeclampsia and severe preeclampsia was changed in the Task Force report to preeclampsia without severe features and preeclampsia with severe features. Preeclampsia without severe features is diagnosed when a patient has:

- systolic BP ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mm Hg (measured twice at least 4 hours apart)

- proteinuria, defined as a 24-hour urine collection of ≥ 300 mg of protein or a urine protein–creatinine ratio of 0.3.

If a patient has elevated BP by those criteria, plus any of several laboratory indicators of multisystem involvement (platelet count, <100 × 103/μL; serum creatinine level, >1.1 mg/dL; doubling in the serum creatinine concentration; liver transaminase concentrations twice normal) or other findings (pulmonary edema, visual disturbance, headaches), she has preeclampsia with severe features. A diagnosis of preeclampsia without severe features is upgraded to preeclampsia with severe features if systolic BP increases to >160 mm Hgor diastolic BP increases to >110 mm Hg (determined by 2 measurements 4 hours apart) or if “severe”-range BP occurs with such rapidity that acute antihypertensive medication is required.

- Incidence of preeclampsia in the United States has increased by 25% over the past 2 decades

- Etiology remains unclear

- Leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality

- Risk factor for future cardiovascular disease and metabolic disease in women

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are major contributors to prematurity

- New best-practice recommendations are urgently needed to guide clinicians in the care of women with all forms of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

- Improved patient education and counseling strategies are needed to convey, more effectively, the dangers of preeclampsia and hypertension during pregnancy

Reference

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. November 2013. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Task-Force-and-Work-Group-Reports/Hypertension-in-Pregnancy. Accessed August 8, 2018.

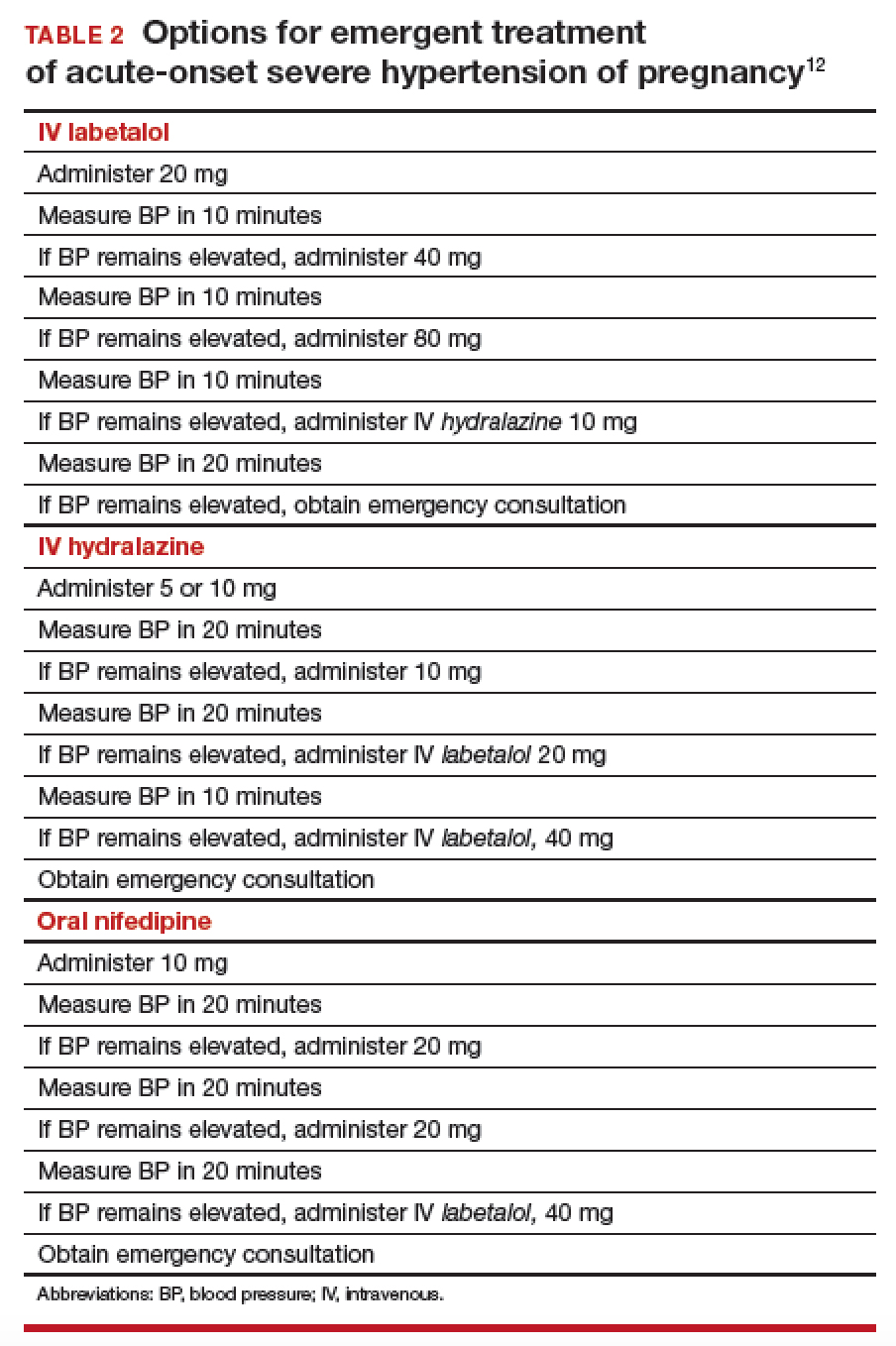

Pharmacotherapy for hypertensive emergency

Acute BP control with intravenous (IV) labetalol or hydralazine or oral nifedipine is recommended when a patient has a hypertensive emergency, defined as acute-onset severe hypertension that persists for ≥ 15 minutes (TABLE 2).12 The goal of management is not to completely normalize BP but to lower BP to the range of 140 to 155 mm Hg (systolic) and 90 to 105 mm Hg (diastolic). Of all proposed interventions, these agents are likely the most effective in preventing a maternal cerebrovascular or cardiovascular event. (Note: Labetalol is contraindicated in patients with severe asthma and in the setting of acute cocaine or methamphetamine intoxication. Hydralazine can cause tachycardia.)13,14

Once a diagnosis of preeclampsia with severe features or superimposed preeclampsia with severe features is made, the patient should remain hospitalized until delivery. If either of these diagnoses is made at ≥ 34 weeks of gestation, there is no reason to prolong pregnancy. Rather, the patient should be given prophylactic magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures and delivery should be accomplished.15,16 Earlier than 36 6/7 weeks of gestation, consider a late preterm course of corticosteroids; however, do not delay delivery in this situation.17

Planning for delivery

Route of delivery depends on customary obstetric indications. Before 34 weeks of gestation, corticosteroids, magnesium sulfate, and prolonging the pregnancy until 34 weeks of gestation are recommended. If, at any time, maternal or fetal condition deteriorates, delivery should be accomplished regardless of gestational age. If the patient is unwilling to accept the risks of expectant management of preeclampsia with severe features remote from term, delivery is indicated.18,19 If delivery is not likely to occur, magnesium sulfate can be discontinued after the patient has received a second dose of corticosteroids, with the plan to resume magnesium sulfate if she develops signs of worsening preeclampsia or eclampsia, or once the plan for delivery is made.

In patients who have either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia without severe features, the recommendation is to accomplish delivery no later than 37 weeks of gestation. While the patient is being expectantly managed, close maternal and fetal surveillance are necessary, comprising serial assessment of maternal symptoms and fetal movement; serial BP measurement (twice weekly); and weekly measurement of the platelet count, serum creatinine, and liver enzymes. At 34 weeks of gestation, conventional antepartum testing should begin. Again, if there is deterioration of the maternal or fetal condition, the patient should be hospitalized and delivery should be accomplished according to the recommendations above.3