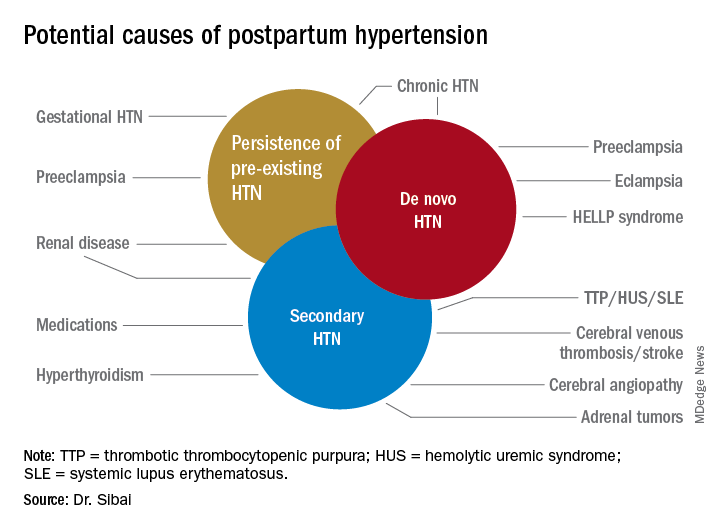

Postpartum hypertension has a host of potential causes, some of which may be benign (such as the persistence of mild gestational hypertension or mild chronic hypertension) whereas others (such as severe de novo preeclampsia-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome [a complication of pregnancy characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and a low platelet count]) can be life threatening.

Postpartum hypertension may occur secondary to lupus, hyperthyroidism, hemolytic uremic syndrome, stroke, and other conditions, which means that we must have a high index of suspicion for secondary dangerous causes of hypertension when evaluating such women.

With monitoring, reporting, and prompt evaluation of symptoms in the postpartum period – and with patient education on signs and symptoms of severe hypertension and preeclampsia (PE) – we can expect to avoid a range of potential maternal complications, from hypertensive encephalopathy, liver hemorrhage, renal failure, and the development of eclampsia, ischemic stroke/cerebral hemorrhage, pulmonary edema, and cardiomyopathy.

Most women with gestational hypertension (GHTN) become normotensive during the first week post partum, but in women who develop PE during pregnancy, hypertension often takes longer to resolve. Some of these women may have an initial decrease in blood pressure immediately post partum followed by development of hypertension again between days 3 and 6. Therefore, This can be achieved either in-hospital, through home BP monitoring, or with in-office visits.

In addition, all women – including those who did not have hypertension during their pregnancies – should be educated about the signs and symptoms of severe hypertension or PE and instructed to report these to a medical provider in a timely fashion. Severe hypertension or PE with severe features may develop for the first time during the postpartum period either before or after hospital discharge. It is important to appreciate, moreover, that approximately 25%-40% of cases of eclampsia develop in the postpartum period with onset ranging from 2 days to 6 weeks after delivery. Moreover, almost one-third of women who develop the HELLP syndrome do so during the postpartum period.

Management of persistent hypertension

The most common causes for persistent hypertension beyond 48 hours after delivery are GHTN, PE, or chronic hypertension. Initial management will depend on history, clinical findings, presence or absence of associated symptoms, results of laboratory findings (urine protein, platelet count, liver enzymes, serum creatinine, and electrolytes), and response to prior treatment of hypertension.

Certain medications that frequently are prescribed in the postpartum period, such as ergonovine and decongestants, should be discontinued if they are being used. These agents can aggravate preexisting hypertension or result in new-onset hypertension if used in large or frequent doses. Their use also may be associated with cerebral symptoms, nausea, and vomiting.

Subsequent management includes close observation until resolution of hypertension and associated symptoms. If the patient has hypertension only with no symptoms, no proteinuria, and normal laboratory findings, BP control is the focus; antihypertensives are used if systolic BP remains persistently greater than or equal to 150 mm Hg and/or if diastolic BP persists at greater than or equal to 100 mm Hg. Intravenous boluses of either labetalol or hydralazine or oral rapid-acting nifedipine are used initially if systolic BP is greater than or equal to 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP greater than or equal to 110 mm Hg persists for at least 30 minutes. This is followed by oral medication to keep systolic BP less than 150 mg Hg and diastolic BP less than 100 mm Hg.

For patients with persistent hypertension after GHTN or PE, I recommend oral long-acting nifedipine XL (30 mg every 12 hours) or oral labetalol (200 mg every 8-12 hours). Compared with labetalol, oral nifedipine is associated with improved renal blood flow with resultant diuresis, which makes it the drug of choice in women with volume overload. In some, it is necessary to switch to a new agent such as an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor; an ACE inhibitor is the drug of choice in those with pregestational diabetes mellitus, renal disease, or cardiomyopathy. In addition, thiazide or loop diuretics may be needed in women with circulatory overload and in those with pulmonary edema. Antihypertensives such as nifedipine, labetalol, furosemide, captopril, and enalapril are compatible with breastfeeding.

If the BP remains less than 150 mm Hg (systolic) and/or less than 100 mm Hg (diastolic) for 24 hours, and there are no maternal symptoms, the patient may be discharged home with instructions for daily BP measurements (self or by a visiting nurse) and the reporting of symptoms until her next visit in 1 week. Antihypertensives then are discontinued if the BP remains below the hypertensive levels for at least 48 hours. This may take 1 or several weeks to achieve.

Women with PE with severe features should receive close monitoring of BP and of symptoms during the immediate postpartum period, as well as accurate measurements of fluid intake, urinary output, and weight gain. These women often have received large amounts of IV fluids during labor as a result of prehydration before epidural analgesia, as well as IV fluids administered during the use of oxytocin and magnesium sulfate in labor and post partum. Mobilization of extracellular fluid also leads to increased intravascular volume. As a result, women who have PE with severe features – particularly those with abnormal renal function, capillary leak, or early-onset disease – are at increased risk for pulmonary edema and exacerbation of severe hypertension.

Careful evaluation of the volume of IV fluids, oral intake, blood products, urine output, respiratory symptoms, and vital signs is advised. Patients who develop tachycardia or respiratory symptoms such as dry cough, shortness of breath, or orthopnea also should be monitored with pulse oximetry and frequent chest auscultation, as well as chest x-ray.