Among peri- and postmenopausal women, abnormal bleeding, breast cancer, and mood disorders represent prevalent conditions. In this Update, we discuss data from a review that provides quantitative information on the likelihood of finding endometrial cancer among women with postmenopausal bleeding (PMB). We also summarize 2 recent consensus recommendations: One addresses the clinically important but controversial issue of the treatment of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) in breast cancer survivors, and the other provides guidance on the management of depression in perimenopausal women.

Endometrial cancer is associated with a high prevalence of PMB

Clarke MA, Long BJ, Del Mar Morillo A, et al. Association of endometrial cancer risk with postmenopausal bleeding in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1210-1222.

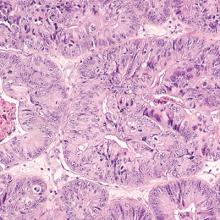

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy and the fourth most common cancer among US women. In recent years, the incidence of and mortality from endometrial cancer have increased.1 Despite the high prevalence of endometrial cancer, population-based screening currently is not recommended.

PMB affects up to 10% of women and can be caused by endometrial atrophy, endometrial polyps, uterine leiomyoma, and malignancy. While it is well known that PMB is a common presenting symptom of endometrial cancer, we do not have good data to guide counseling patients with PMB on the likelihood that endometrial cancer is present. Similarly, estimates are lacking regarding what proportion of women with endometrial cancer will present with PMB.

To address these 2 issues, Clarke and colleagues conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of PMB among women with endometrial cancer (sensitivity) and the risk of endometrial cancer among women with PMB (positive predictive value). The authors included 129 studies--with 34,432 women with PMB and 6,358 with endometrial cancer--in their report.

Cancer prevalence varied with HT use, geographic location

The study findings demonstrated that the prevalence of PMB in women with endometrial cancer was 90% (95% confidence interval [CI], 84%-94%), and there was no significant difference in the occurrence of PMB by cancer stage. The risk of endometrial cancer in women with PMB ranged from 0% to 48%, yielding an overall pooled estimate of 9% (95% CI, 8%-11%). As an editorialist pointed out, the risk of endometrial cancer in women with PMB is similar to that of colorectal cancer in individuals with rectal bleeding (8%) and breast cancer in women with a palpable mass (10%), supporting current guidance that recommends evaluation of women with PMB.2 Evaluating 100 women with PMB to diagnose 9 endometrial cancers does not seem excessive.

Interestingly, among women with PMB, the prevalence of endometrial cancer was significantly higher among women not using hormone therapy (HT) than among users of HT (12% and 7%, respectively). In 7 studies restricted to women with PMB and polyps (n = 2,801), the pooled risk of endometrial cancer was 3% (95% CI, 3%-4%). In an analysis stratified by geographic region, a striking difference was noted in the risk of endometrial cancer among women with PMB in North America (5%), Northern Europe (7%), and in Western Europe (13%). This finding may be explained by regional differences in the approach to evaluating PMB, cultural perceptions of PMB that can affect thresholds to present for care, and differences in risk factors between these populations.

The study had several limitations, including an inability to evaluate the number of years since menopause and the effects of body mass index. Additionally, the study did not address endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia.

PMB accounts for two-thirds of all gynecologic visits among perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 This study revealed a 9% risk of endometrial cancer in patients experiencing PMB, which supports current practice guidelines to further evaluate and rule out endometrial cancer among all women presenting with PMB4; it also provides reassurance that targeting this high-risk group of women for early detection and prevention strategies will capture most cases of endometrial cancers. However, the relatively low positive predictive value of PMB emphasizes the need for additional triage tests with high specificity to improve management of PMB and minimize unnecessary biopsies in low-risk women.

Treating GSM in breast cancer survivors: New guidance targets QoL and sexuality

Faubion SS, Larkin LC, Stuenkel CA, et al. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25:596-608.

More than 3 million breast cancer survivors reside in the United States. Accordingly, ObGyns see survivors on a frequent basis. For several reasons, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (also known as vulvovaginal atrophy) is particularly prevalent in women who have been treated for breast cancer. Chemotherapy, for example, often induces ovarian failure. For some premenopausal women, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be performed or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists may be prescribed as part of breast cancer treatment. In postmenopausal survivors with hormone receptor-positive tumors, adjuvant aromatase inhibitor (AI) therapy may be used for up to 10 years. Treatment with AIs is associated with GSM symptoms.5 Although vaginal estrogen is an effective treatment for GSM, package labeling for all estrogens, including vaginal estrogens, lists a personal history of breast cancer as a contraindication.Given that there is little evidence addressing the safety of vaginal estrogen, other hormonal therapies, and nonprescription treatments for GSM in breast cancer survivors, many survivors with bothersome GSM symptoms are not appropriately treated.

Continue to: Expert panel creates evidence-based guidance...