The institutional involvement in malpractice cases also may affect apparent malpractice rates in another way. The National Practitioner Data Bank, which is the source of information for many malpractice studies, only requires reporting about individual physicians, not institutions.14 If, therefore, claims are settled on behalf of an institution, without implicating the physician, the number of physician malpractice cases may appear to decline without any real change in malpractice rates.14 In addition, institutions have taken the lead in informal resolution of injuries that occur in the institution, and these programs may reduce the direct malpractice claims against physicians. (These “disclosure, apology, and offer,” and similar programs, are discussed in the upcoming third part of this series.)

The medical reform factor

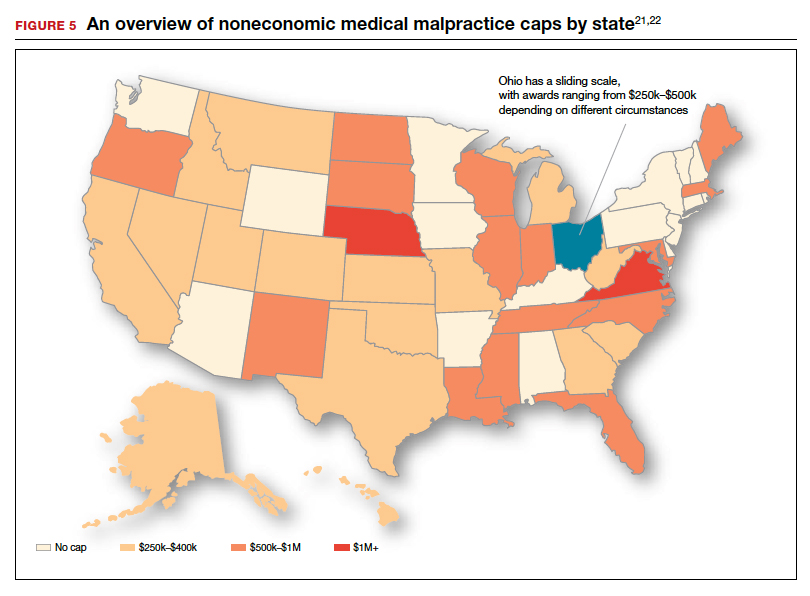

As noted, annual rates paid for medical malpractice in our specialty are trending downward. Many commentators look to malpractice reforms as the reason for the drop in malpractice rates.15-17 Because medical malpractice is essentially a matter of state law, the medical malpractice reform has occurred primarily at the state level.18 There have been many different reforms tried—limits on expert witnesses, review panels, and a variety of procedural limitations.19 Perhaps the most effective reform has been caps being placed on noneconomic damages (generally pain and suffering).20 These caps vary by state (FIGURE 5)21,22 and, of course, affect the “big verdict” cases. (As we saw in the second case scenario above, Virginia is an example of a state with a cap on malpractice awards.) They also have the secondary effect of reducing the number of malpractice cases. They make malpractice cases less attractive to some attorneys because they reduce the opportunity of large contingency fees from large verdicts. (Virtually all medical malpractice cases in the United States are tried on a contingency-fee basis, meaning that the plaintiff does not pay the attorney handling the case but rather the attorney takes a percentage of any recovery—typically in the neighborhood of 35%.) The reform process continues, although, presently, there is less pressure to act on the malpractice crisis.

Medical malpractice cases are emotional and costly

Another reason for the relatively low rate of paid claims is that medical malpractice cases are difficult, emotionally challenging, time consuming, and expensive to pursue.23 They typically drag on for years, require extensive and expensive expert consultants as well as witnesses, and face stiff defense (compared with many other torts). The settlement of medical malpractice cases, for example, is less likely than other kinds of personal injury cases.

The contingency-fee basis does mean that injured patients do not have to pay attorney fees up front; however, plaintiffs may have to pay substantial costs along the way. The other side of this coin is that lawyers can be reluctant to take malpractice cases in which the damages are likely to be small, or where the legal uncertainty reduces the odds of achieving any damages. Thus, many potential malpractice cases are never filed.

A word of caution

The news of a reduction in malpractice paid claims may not be permanent. The numbers can conceivably be cyclical, and political reforms achieved can be changed. In addition, new technology will likely bring new kinds of malpractice claims. That appears to be the case, for example, with electronic health records (EHRs). One insurer reports that EHR malpractice claims have increased over the last 8 years.24 The most common injury in these claims was death (25%), as well as a magnitude of less serious injuries. EHR-related claims result from system failures, copy-paste inaccuracies, faulty drop-down menu use, and uncorrected “auto-populated” fields. Obstetrics is tied for fifth on the list of 14 specialties with claims related to EHRs, and gynecology is tied for eighth place.24

Continue to: A federal court ruled that a hospital that changed from...