A common infection

While three-quarters of women will experience VVC at least once in their lifetime, between 40% and 45% will experience it more than once, and 5% to 8% will develop recurrent VVC. Among pregnant women, 15% will develop symptomatic VVC.1,2

However, because VVC is not a reportable disease and antifungal medication is available over the counter without physician consultation, these numbers likely underestimate the true incidence of the infection.4

Complications in pregnancy

Vaginal infections, including VVC, bacterial vaginosis (BV), and trichomoniasis, may be associated with 40% of preterm deliveries.5 The high concentrations of estrogen and progesterone during pregnancy create a uniquely glycogen-rich vaginal environment in which Candida species can flourish.2,4 Even asymptomatic colonization of the vagina with Candida species has been associated with preterm labor, preterm birth, and low birth weight.1,6 This association appears to have more severe consequences if VVC occurs in the second trimester compared with the first trimester.6

Additionally, congenital candidiasis of the newborn may result from intrauterine Candida infection or heavy maternal vaginal colonization at delivery, and the infection is evident within 24 hours of birth. It presents typically as oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush) of the newborn.1

Clinical manifestations of infection

The classic manifestations of Candida infection are similar in both the pregnant and nonpregnant patient: acute vaginal and vulvar pruritus and thick, white, malodorous “cottage cheese” vaginal discharge.1,4 Exercise caution, however, in treating presumptively based on these symptoms alone, especially in pregnancy, because they are not specific to candidiasis.4 Vaginal discharge is not always present, and it may vary in appearance and odor. Pruritus is the most specific symptom of Candida infection, but studies show that it is an accurate predictor in only 38% of cases.7

Other common signs and symptoms include the sensation of burning, dysuria, dyspareunia, fissures, excoriations, and pruritus ani. Physical examination demonstrates erythema and swelling of labial, vulvar, and vaginal structures, with a normal cervix and an adherent white or off-white discharge. When the discharge is removed from the vaginal wall, small bleeding points may appear.1,4

Making the diagnosis

As mentioned, history alone is not sufficient to make a definitive diagnosis of candidiasis. The diagnosis should be made by examining vaginal secretions under a microscope or by culture.4 A wet mount and KOH (potassium hydroxide) prep help differentiate VVC, BV, and trichomoniasis. Culture is particularly valuable in identifying less common fungal organisms, such as C glabrata and C tropicalis.

Vaginal pH testing is not conclusive for Candida because vaginal pH is normal in VVC. However, pH assessment can rule in other causative organisms if the value is abnormal (that is, elevated pH of 4.5 or greater with BV and trichomoniasis).1

Treatment options

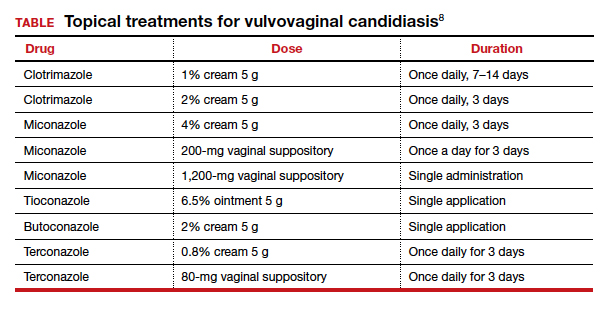

Acute infection. A pregnant woman who tests positive for VVC may safely be treated in any trimester with a 7-day course of a topical azole.8 If the patient prefers the convenience of oral therapy, after the first trimester, oral fluconazole, 150 mg on day 1 and day 3, may be used for treatment. Note that fluconazole has been associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and cardiac septal defects when used in the first trimester.1

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a number of topical treatments for VVC (TABLE).8 Several of these drugs are available over the counter without a prescription. Topical azoles are more effective than nystatin in treating VVC, and posttreatment cultures are negative in up to 90% of treated patients.8

Recurrent infections. Recurrent VVC is defined as 4 or more episodes of symptomatic VVC within 12 months.8 Typical first-line treatment of recurrent infections in nonpregnant patients is a 6-month course of fluconazole, 150 mg weekly.9,10 As noted, however, fluconazole should not be used in the first trimester of pregnancy. It is acceptable therapy thereafter for patients who have troublesome recurrent or persistent infections.

Continue to: Strategies for preventing recurrence...