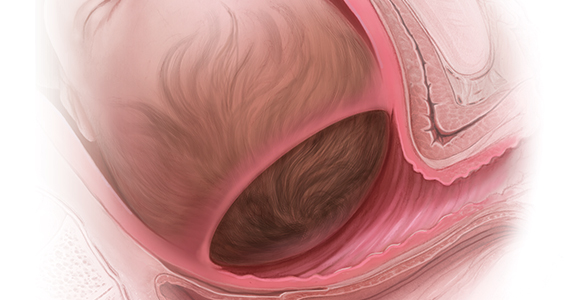

CASE Woman in second stage with prolonged pushing

Ms. J. is an 18-year-old woman (G1P0) at 39 weeks’ gestation whose cervix is completely dilated; she has been actively pushing for 60 minutes. The estimated fetal weight is 8 lb, and electronic fetal monitoring shows a Category I fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing. The presenting part remains at 0 station and occiput transverse despite great pushing effort.

After another hour of active pushing, the FHR becomes Category II with repetitive variable decelerations. During the third hour of the second stage, Ms. J. is diagnosed with chorioamnionitis and the fetus remains at 0 station. She undergoes a primary cesarean delivery (CD) complicated by bilateral lower uterine extensions and postpartum hemorrhage. The birth weight was 4,100 g, and 5- and 10-minute Apgar scores were 4 and 8, respectively. The umbilical cord arterial pH was 7.03.

Ms. J. and her baby were discharged home on postoperative day 4.

In 2014, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine jointly released a document, “Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery,” in response to the sharp rise in cesarean births from 1996 to 2011.1 It described management strategies to safely reduce the most common indications for a primary CD in nulliparous women. Specifically, it recommended that the second stage of labor—defined as the interval from complete cervical dilation through delivery of the neonate—may be prolonged, as “longer durations may be appropriate on an individualized basis (eg, with the use of epidural analgesia or with fetal malposition) as long as progress is being documented.”1

A prolonged second stage was defined as 3 hours of pushing in nulliparous women and 2 hours in multiparous women, with 1 additional hour (or longer) in those receiving epidural analgesia. Indeed, the primary CD rate decreased slightly to 21.7% in 2018, down from 21.9% in 2017.2 More recent evidence, however, has shown an increase in maternal and neonatal morbidity with prolonged second stage.3-8

Efforts to manage the second stage from an evidence-based perspective are critical to balance the desired outcome of a safe vaginal delivery against the risks of prolonged second stage and operative vaginal delivery or CD.

Perspectives on the “ideal” labor duration

It is important to consider the historical context that led to the 2014 change in recommendations for duration of the second stage.9 In 1955, Dr. Emanuel Friedman published a prospective observational study of 622 consecutive primigravid parturients at term, of which 500 were included in the analysis that led to the graphicostatistical labor curve, or the well-known “Friedman’s curve.”10 The mean duration of the second stage was 0.95 hour. The statistical maximum for “ideal labor” for the second stage was set at 2 hours, with an additional hour allotted for patients receiving epidural analgesia.

In 2010, Zhang and colleagues published contemporary labor curves using data from the Consortium on Safe Labor, a multicenter retrospective observational study of 62,415 parturients.11 Among more than 25,000 nulliparous women, the median duration (95th percentile) of the second stage in hours was 1.1 (3.6), respectively. Notably, this analysis included only women with a spontaneous vaginal delivery and normal neonatal outcome.

Prior to the publication of the “Safe prevention of primary cesarean delivery,” multiple investigations examined the relationship between the duration of the second stage and adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes, and the findings have been inconsistent.12-15

For example, Cheng and colleagues noted increased maternal complications that included postpartum hemorrhage, third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, and chorioamnionitis, but not neonatal morbidity, with each increasing hour within the second stage.12 By contrast, a large, population-based cohort study among low-risk women showed an increase in low 5-minute Apgar scores, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and composite perinatal morbidity with prolonged second stage.15 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the Pushing Early or Pushing Late with Epidural (PEOPLE) trial showed that the chances of a vaginal delivery with a newborn without signs of asphyxia decreased significantly every hour after the first hour, and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage and intrapartum fever increased significantly after 2 hours of pushing.14

While these findings may represent the risks inherent with the intervention of operative delivery and not the duration of second stage of labor per se, one could posit that if the intervention were initiated earlier, could it prevent or at least reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity?

Continue to: Factors to assess and monitor in the second stage...