Classifying FGC types

The WHO has classified FGC into 4 different types1:

- type 1, partial or total removal of the clitoris or prepuce

- type 2, partial or total removal of part of the clitoris and labia minora

- type 3 (also known as infibulation), the narrowing of the vaginal orifice by cutting, removing, and/or repositioning the labia, and

- type 4, all other procedures to the female genitalia for nonmedical reasons.

Long-term complications

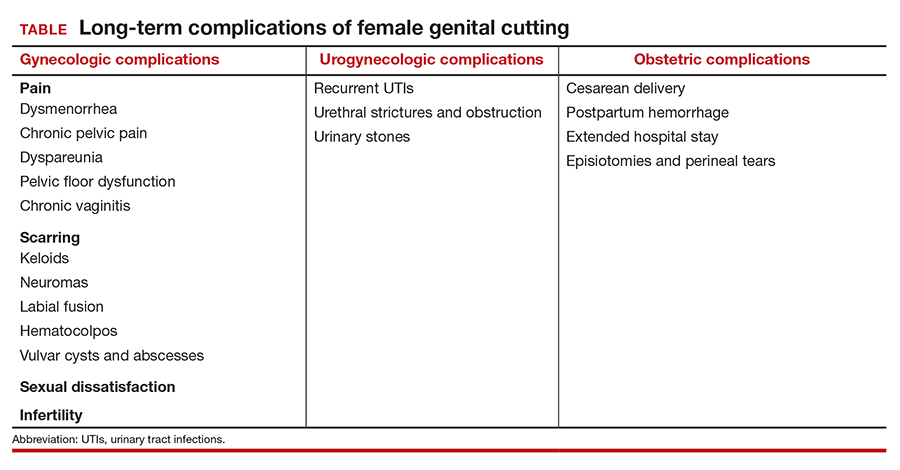

Female genital cutting, especially types 2 and 3, can lead to long-term obstetric and gynecologic complications that the ObGyn should be able to diagnose and manage (TABLE).

The most common long-term complications of FGC are dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, recurrent vaginal and urinary tract infections, and sexual dysfunction/dissatisfaction.10 One recent cross-sectional study that used validated questionnaires on pelvic floor and psychosexual symptoms found that women with FGC had higher distress scores than women who had not undergone FGC, indicating various pelvic floor symptoms responsible for impact on their daily lives.11

Infertility can result from a combination of physical barriers (vaginal stenosis and an infibulated scar) and psychologic barriers secondary to dyspareunia, for example.12 Labor and delivery also presents a challenge to both patients and providers, especially in cases of infibulation. Studies show that patients who have undergone FGC are at increased risk of adverse obstetric outcomes, including postpartum hemorrhage, episiotomy, cesarean delivery, and extended hospital stay.13 Neonatal complications, including infant resuscitation and perinatal death, are more commonly reported in studies outside the United States.13

Clinical management recommendations

It is important to be aware of the WHO FCG classifications and be able to recognize evidence of the procedure on examination. The ObGyn should perform a detailed physical exam of the external genitalia as well as a pelvic floor exam of every patient. If the patient does not disclose a history of FGC but it is suspected based on the examination, the clinician should inquire sensitively if the patient is aware of having undergone any genital procedures.

Especially when a history of FGC has been confirmed, clinicians should ask patients sensitively about their urinary and sexual function and satisfaction. Validated tools, such as the Female Sexual Function Index, the Female Sexual Distress Scale, and the Pelvic Floor Disability Index, may be helpful in gathering an objective and detailed assessment of the patient’s symptoms and level of distress.14 Clinicians also should ask about the patient’s detailed obstetric history, particularly regarding the second stage, delivery, and postpartum complications. The clinician also should specifically inquire about a history of defibulation or additional genital procedures.

Patients with urethral strictures or stenosis may require an exam under anesthesia, cystoscopy, urethral dilation, or urethroplasty.12 Those with chronic urinary tract or vaginal infections may require chronic oral suppressive therapy or defibulation (described below). Defibulation also may be considered for relief of severe dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia that may be resulting from hematocolpos. The ObGyn also should make certain to evaluate for other common causes of these symptoms that may be unrelated to FGC, such as endometriosis.

Many women who have undergone FGC do not report dyspareunia or sexual dissatisfaction; however, infibulation especially has been associated with higher rates of these sequelae.12 In addition to defibulation, pelvic floor physical therapy with an experienced therapist may be helpful for patients with pelvic floor dysfunction, vaginismus, and/or dyspareunia.

The defibulation procedure

Defibulation (or deinfibulation) is a surgical reconstructive procedure that opens the infibulated scar of patients who have undergone type 3 FGC (infibulation), thus exposing the urethra and introitus, and in almost half of cases an intact clitoris.15 Defibulation may be specifically requested by a patient or it may be recommended by the ObGyn either for reducing complications of pregnancy or to address the patient’s gynecologic, sexual, or urogynecologic symptoms by allowing penetrative intercourse, urinary flow, physiologic delivery, and menstruation.16

Defibulation should be performed under regional or general anesthesia and can be performed during pregnancy (or even in labor). An anterior incision is made on the infibulated scar, creating a new labia major, and the edges are sutured separately. Postoperatively, patients should be instructed to perform sitz baths and to expect a change in their urinary voiding stream.12 The few studies that have evaluated defibulation have shown high rates of success in addressing preoperative symptoms; the complication rates of defibulation are low and the satisfaction rates are high.16

The ethical conundrum of reinfibulation

Reinfibulation is defined as the restitching or reapproximation of scar tissue or the labia after delivery or a gynecologic procedure, and it is often performed routinely after every delivery in patients’ countries of origin.17

Postpartum reinfibulation on patient request raises legal and ethical issues for the ObGyn. In the United Kingdom, reinfibulation is illegal, and some international organizations, including the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics and the WHO, have recommended against the practice. In the United States, reinfibulation of an adult is legal, as it falls under the umbrella of elective female genital cosmetic surgery.18,19

The procedure could create or exacerbate long-term complications and should generally be discouraged. However, if despite extensive counseling (preferably in the prenatal period) a patient insists on having the procedure, the ObGyn may need to elevate the principle of patient autonomy and either comply or find a practitioner who is comfortable performing it. One retrospective review in Switzerland suggested that specific care and informative counseling prenatally with the inclusion of a patient’s partner in the discussion can improve the acceptability of defibulation without reinfibulation.20

Conclusion

It is important for ObGyns to be familiar with the practice of FGC and to be trained in its recognition on examination and care for the long-term complications that can result from the practice. At the same time, ObGyns should be especially conscious of their biases in order to provide culturally competent care and reduce health care stigmatization and inequities for these patients.