Pregnancy and the postpartum period are times of increased risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE). While VTE is a rare event overall, it is responsible for more than 9% of maternal deaths in the United States.1 The increased risk of VTE exists throughout pregnancy, rising in the third trimester.2 The highest-risk period is the first 6 weeks postpartum, likely peaking in the first 2 to 3 weeks and returning to baseline at about 12 weeks postpartum.2,3

To reduce this source of maternal harm, the National Partnership for Maternal Safety and the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care recommend the use of VTE prevention bundles. Bundles include standard assessment of risk during prenatal care, any admission to the hospital, and postpartum coupled with standard recommendations for treatment.4-6 Multiple published guidelines are available for prevention of VTE in pregnancy, and they provide varying recommendations on patient selection and treatment. Many of these recommendations are based on low quality of evidence, making the choice of standard practice difficult.

In this article, I attempt to simplify patient selection and treatment based on currently published guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Society of Hematology (ASH), and expert opinion.

Determining VTE risk and need for prophylaxis

CASE 1 Woman with factor V Leiden

A 25-year-old woman (G1P0) presents for her initial prenatal visit. She says she is a carrier for factor V Leiden but has never had a clot. She was tested after her sister had a VTE. She asks, does she need VTE prophylaxis before her delivery?

What are the considerations and options for this patient?

Options for VTE prophylaxis

Before considering patients at risk for VTE, it is helpful to review the options for prophylaxis. Patients can undergo clinical surveillance or routine care with attention to VTE symptoms and a low threshold for workup.

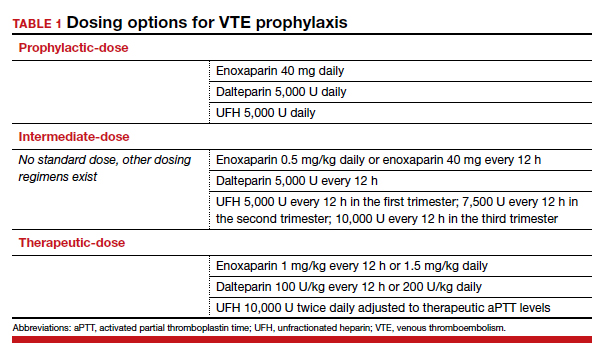

There are 3 categories of chemoprophylaxis for prevention of VTE. (TABLE 1 offers examples of dosing regimens.) No strategy has been proven optimal over another:

- prophylactic-dose: the lowest, fixed dose.

- intermediate-dose: lacks a standard definition and is any dose higher than prophylactic-dose but lower than therapeutic-dose. This includes fixed twice-daily doses, weight-based doses, and incrementally increasing doses.

- therapeutic-dose: typically used for treatment but mentioned here since patients with high-risk conditions may use it for prevention of VTE.

The preferred agent for VTE chemoprophylaxis is low molecular weight heparin (LMWH; dalteparin, enoxaparin). LMWH has a lower risk of complications than unfractionated heparin (UFH) and can be injected once daily. LMWH and UFH do not cross the placenta. LMWH and UFH are safe in breastfeeding. Oral direct thrombin inhibitors and anti-Xa inhibitors are not recommended in pregnancy or lactation at this time. Warfarin is avoided in pregnancy except in situations with mechanical heart valves, which will not be addressed here. Patients taking warfarin for long-term anticoagulation can transition back while breastfeeding with appropriate bridging.

Expert opinion recommends antepartum chemoprophylaxis when there is a 2% to 3% risk of VTE in pregnancy.7-9 This is balanced against an approximately 2% overall risk of bleeding, with less than 1% risk of bleeding antepartum.9

Continue to: Risk factors for VTE...