High mammographic breast density is associated with increased risk of developing breast cancer, but not with increased risk of death among those diagnosed with breast cancer, according to an analysis of data from the U.S. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium.

Low breast density is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer death, however, in women who are obese or who have large or high-grade tumors, Gretchen L. Gierach, Ph.D., of the National Cancer Institute and her colleagues reported.

Specifically, the elevated risk was apparent for obese women (body mass index 30 kg/m2 or greater) with "almost entirely fatty breasts." This association was not apparent in overweight or lean women.

"One explanation for the increased risks associated with low density among some subgroups is that breasts with a higher percentage of fat may contribute to a tumor microenvironment that facilitates cancer growth and progression," the investigators suggested.

The findings were published Aug. 20 online in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Prior studies have demonstrated that elevated mammographic breast density is among the strongest risk factors for nonfamilial breast cancer. High breast density is also associated with breast cancer risk factors including nulliparity, a positive family history of breast cancer, and menopausal hormone therapy use, but studies have consistently demonstrated that "compared with low density, high density confers relative risks of four- to fivefold for breast cancer, independent of these and other factors," the investigators said.

The association between breast density and death among those diagnosed with breast cancer has remained unclear, however. To assess this relationship, they analyzed data from the U.S. Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) – a National Cancer Institute–sponsored population-based registry of breast imaging facilities.

"The BCSC offers several advantages for studying these associations relative to other studies, including the prospective follow-up of a large number of breast cancer patients with detailed information regarding potential confounding factors, including BMI, as well as on screening history, tumor characteristics, and treatment," the investigators noted.

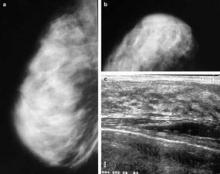

The analysis was restricted to women aged 30 years and older at the time of diagnosis with primary incident invasive breast carcinoma. Breast cancer pathology and vital status data were obtained through the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and by linkage to state cancer registries and/or pathology databases. Breast density data were collected according to the American College of Radiology’s Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System, or BI-RADS, which rates density in categories from 1 (almost entirely fat) to 4 (extremely dense).

The study population comprised 9,232 women diagnosed with primary invasive breast cancer between 1996 and 2005 and followed for a mean of 6.6 years (60,759 person-years) as part of the consortium. Of these 1,795 died, including 889 who died from their breast cancer.

After adjustment for site, age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, BMI, mode of detection, treatment, and income, no significant association was found between BI-RADS 4 density and death from breast cancer (hazard ratio, 0.92) or death from all causes (HR, 0.83), compared with BI-RADS 2 (scattered fibroglandular densities).

Women with BI-RADS 1 density had an elevated risk for breast cancer death (HR, 1.36), and that risk was further increased among those with tumors of at least 2.0 cm (HR, 1.55), and those with high-grade tumors (HR, 1.45), the investigators reported (J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012 Aug. 20 [doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs327]).

BMI was found to modify the relationship between breast density and risk of breast cancer death (P for interaction = .007). The investigators reported a hazard ratio of 2.02 in obese women with "almost entirely fatty" breasts, and noted that it remained apparent even if morbidly obese women with BMI greater than 40 were excluded.

Although the study is limited by "moderate interobserver reliability" with respect to BI-RADS density assessment, and by the fact that that detailed, cumulative information on treatment, comorbidities, and changes in weight after diagnosis was limited, the findings raise additional questions about possible interactions between breast density, other patient characteristics, and subsequent treatment, the investigators said.

"It is reassuring that elevated breast density, a prevalent and strong breast cancer risk factor, was not associated with risk of breast cancer death or death from any cause in this large, prospective study," they said.

"However, we identified subsets of women with breast cancer for whom low density was associated with adverse prognoses, highlighting the possibility of integrating breast density with epidemiological data and other measurements to understand mechanisms of breast carcinogenesis and to identify women who are likely to develop aggressive cancers, which might be preventable or detectable through specific interventions," they said.