As is the case with variable recurrent decelerations, the presence of accelerations or moderate FHR variability, or both, provides reassurance that the baby is doing well at that point. Evaluating for the presence of these factors is important and can be most helpful with recurrent late decelerations, as these patterns in general are poorly predictive for acidemia.

If late decelerations continue in the setting of minimal FHR variability and absent accelerations, despite intrauterine resuscitation efforts, the presence of fetal acidemia should be considered and the potential need for expedited delivery should be evaluated.

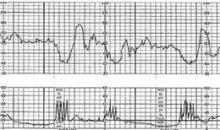

• Fetal Tachycardia. Intrapartum fetal tachycardia, defined as a baseline heart rate greater than 160 beats/min for at least 10 minutes, is a fairly common occurrence in labor. When the FHR is extremely high – greater than 200 beats/min – one should consider fetal tachyarrhythmias. These are uncommon, and it is somewhat unlikely for them to occur for the first time during labor (they are more commonly identified antepartum).

When the FHR is high but in the range of approximately 160-180 beats/min, evaluation for chorioamnionitis and other maternal infections is important. If a fever is present, broad-spectrum antibiotics should be administered.

Again, even in the case of fetal tachycardia, the presence of minimal variability and/or accelerations tells us that the baby is probably not acidemic.

• Bradycardia, Prolonged Decelerations. Intrapartum bradycardia and prolonged decelerations differ mainly in their duration. The patterns are similarly managed since, as the practice bulletin says, clinical intervention is often indicated before a distinction between the two can be made.

In either case, we need to be concerned about the possibility of maternal hypotension (for example, postepidural), umbilical cord prolapse or occlusion, placental abruption, rapid fetal descent, tachysystole, or uterine rupture. Essentially, we must evaluate all these potential causes by performing a vaginal exam to determine whether the baby’s head has descended quickly or whether the umbilical cord has fallen ahead of the baby, for example, and by checking the mother’s blood pressure. Significant bleeding would signal placental abruption. And, in the case of significant bradycardia, uterine rupture becomes a major concern, especially in women with a prior cesarean.

Management is directed at the underlying cause and at resuscitating and supporting the baby with the use of fluid, oxygen, and other targeted measures.

Category III: Timing of Delivery

As part of its framework for managing FHR patterns based on the three-tiered categorization, ACOG’s 2010 Practice Bulletin also addresses the critical question of the timing of emergent cesarean delivery. Category III tracings most often require prompt delivery when intrauterine resuscitation measures are unsuccessful. Multiple studies, however, have called into question the 30-minute decision-to-incision time that historically has been the guiding principle in the setting of abnormal Category III patterns.

In one study published in 2006 involving 2,808 women who had cesarean deliveries for emergency indications including umbilical cord prolapse, placental abruption, and "nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern," adverse neonatal outcomes were not increased among infants delivered after more than 30 minutes. (Approximately one-third of the emergency cesarean deliveries began more than 30 minutes after the decision to operate was made, and most of these deliveries were for nonreassuring FHR tracings.)

In fact, the vast majority of those delivered after 30 minutes – 95% – did not experience a measure of newborn compromise (Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;108:6-11). Other studies have similarly failed to show any association of increased adverse outcomes with a 30-minute time frame.

Rather than thinking about deliveries within 30 minutes, we should deliver based on timing that best incorporates maternal and fetal risks and benefits, as the practice bulletin states. The bottom line, in other words, is to accomplish delivery both as expeditiously as possible and as safely as possible for the baby and for the mother. There is no single optimal time frame. A mother with morbid obesity and significant anesthesia risk, for instance, may require more stabilization or surgical preparation than a mother without such a high-risk condition.

Dr. Macones is the Mitchell and Elaine Yanow professor and chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Macones said he had no relevant financial disclosures.