Prior to discharge, attempt a bladder challenge (usually postoperative day 2). In the rare instance the woman is unable to void, discharge the patient and repeat the bladder challenge in 1 week.

Figure 2

After dividing the bladder pillar, located between the vesicovaginal and paravesical spaces, identify the ureter (the tubular structure at 12 o’clock).

Figure 3

Access the posterior cul-de-sac and the pararectal spaces, and then divide the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments 2 cm from the cervix.

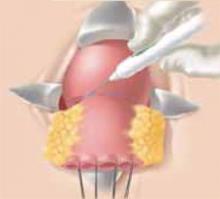

Figure 4

After retracting the ureters and clamping the descending branch of the uterine artery, resect the cervix 0.5 to 1 cm distal to the isthmus.

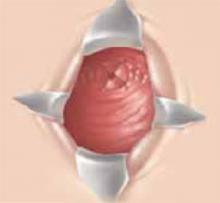

Figure 5

If the proximal incision margin has cleared the cancer, close the peritoneum and place a cerclage using a strong nonabsorbable suture.

Figure 6

Finally, suture the vaginal mucosa to the cervical stump, not to the mucosa, to help prevent postoperative stenosis.

Complications

The rate of morbidity associated with this procedure varies from 13% to 25%.3-5 (In the hands of an experienced surgeon, the complication rate is comparable to that of radical hysterectomy.) Dargent et al reported complications in 7 of 47 women (1 required reoperation for sidewall hemorrhage, 5 had postoperative hematomas, and 1 had prolonged urinary retention).3 Similarly, Roy and Plante reported 2 external iliac artery injuries, 1 conversion to laparotomy for hemostasis, and 1 cystotomy among 30 patients who underwent the procedure.4 Covens et al encountered complications in 8 of 32 women, including 6 cystotomies, 1 enterotomy, and 1 external iliac artery injury.5 It is important to note that the vascular injuries most commonly occurred during the lymphadenectomy. To date, no operative mortalities have been reported in association with radical trachelectomy.

Oncologic outcome

Roy recently summarized the oncologic outcome of women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy for early-stage cervical cancer at medical centers in Lyon, Quebec, and Toronto.7 This data, as well as that from London and the Women’s Hospital in Los Angeles, are shown in Table 1. (Women who underwent radical trachelectomy followed by hysterectomy due to lack of lesion clearance are excluded.)

Among the almost 200 cases, the cancer recurrence rate is low, and viable pregnancies are clearly possible.

Seven of 197 women (3.5%) had positive lymph nodes discovered postoperatively. However, all of them have remained disease-free. (Most of the women received pelvic radiotherapy postoperatively.) To date, there have been 6 recurrences (3%) reported, 2 of which have been in women with neuroendocrine tumors (a histology associated with an especially poor prognosis). Excluding the 2 neuroendocrine tumors, the recurrence rate drops to 2.1%. All of the 4 remaining women had negative lymph nodes and LVSI, and 2 had lesions larger than 2 cm (Table 2).

Of the 92 women whose cervical cancers did not invade the lymph-vascular space, none experienced a recurrence. Similarly, smaller tumors were associated with a low recurrence rate; in women with lesions 2 cm or smaller, only 1.6% had a recurrence. Women with lesions larger than 2 cm or with LVSI had a somewhat higher recurrence rate (10.5% and 11.1%, respectively), as would be expected based on our knowledge of recurrence risk after radical hysterectomy (Table 3).8,9

There are no prospective randomized trials that have analyzed oncologic outcome in women undergoing radical vaginal trachelectomy as compared to radical hysterectomy. Clearly, such a trial would not be feasible. However, the results of a 1999 retrospective case-control study are promising. In this trial, Covens compared the outcome of 32 women who underwent radical vaginal trachelectomy (all of whom had negative nodes and none of whom received radiation) to that of 30 women who underwent radical hystererctomy (matched for age, tumor size, histology, depth of invasion, and presence of LVSI).5 A second, unmatched, control group consisted of all women who had undergone radical hysterectomy for tumors 2 cm or smaller, had negative nodes, and had not received postoperative pelvic radiation. After a median follow-up of 23.4 months for the study patients, 46.5 months for the matched control patients, and 50.3 months for the unmatched control group, the 2-year actuarial recurrence-free survival was 95%, 97%, and 100%, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

TABLE 1

Oncologic outcome

| LYON N=71 | QUEBEC N=43 | TORONTO N=53 | LOSANGELES N=20 | LONDON N=9 | TOTAL N=196 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up (mean) | 60 | 36 | 30 | 18.5 | 2 | - |

| Positive nodes | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 7 (3.5%) |

| Recurrence | 3* | 2* | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6† (3%) |

| *One patient in each had a neuroendocrine tumor | ||||||

| †Recurrence rate is 2.1%, if women with neuroendocrine tumors are excluded. | ||||||

TABLE 2

Recurrences after radical vaginal trachelectomy*

| SIZE | HISTOLOGY | LN STATUS | LVSI | SITE | STATUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Aortic LN | DOD |

| 2.5 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvic LN | NED |

| 3 cm | Squamous | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| <2 cm | Adenocarcinoma | Negative | Yes | Pelvis | DOD |

| LN=lymph node | |||||

| LVSI=lymph-vascular space involvement | |||||

| DOD=dead of disease | |||||

| NED=no evidence of disease | |||||

| *Neuroendocrine tumors excluded | |||||

TABLE 3