Finally, close the suprapubic and vaginal incisions with absorbable sutures.

Placing autologous or allogenic slings. Fashion the graft, typically 2 cm wide and 10 to 12 cm long, with permanent sutures at the edges. Make a 1-cm incision into the suprapubic rectus fascia. Use either a Stamey-type needle trocar or uterine packing forceps and guide the instrument “top down” from the retropubic incision to the vaginal tunnel. The tunnel is made directly into the retropubic space from the vaginal incision. Bring the sling arms up on each side. Attach the arms to the rectus fascia and tie them down once cystoscopy and the tension test are complete.

The sling also can be performed with bone anchors placed through the vaginal incision into the pubic bone. Placement requires vaginal dissection into the retropubic space with no suprapubic incision. Once anchored, the sutures are then passed through the chosen graft materials and tied down. Bear in mind that anchoring into the periosteum of the pubic bone may cause severe osteomyelitis or osteitis pubis, though the actual incidence is unknown.7

FIGURE 1 Surgical steps for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT)

Place a Sims speculum into the vagina and make a vertical incision 1.5 cm from the external urethra meatus.

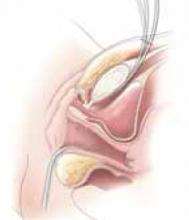

FIGURE 2

Use Metzenbaum scissors to dissect the vaginal mucosa from the underlying fascia bilaterally. Insert a Foley catheter with guide.

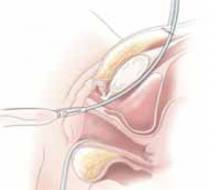

FIGURE 3

Place TVT trocars through the vaginal incision. Place abdominal guides suprapubically and attach them to the TVT trocar tip.

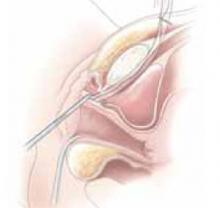

FIGURE 4

Push the tape through the retropubic space, keeping the trocar in close contact with the posterior surface of the pubic bone.

FIGURE 5

Continue pushing the trocar through the urogenital diaphragm until its tip comes through the suprapubic incision on the ipsilateral side.

FIGURE 6 Surgical steps for SPARC

Guide the needle down the posterior side of the pubic bone, keeping the needle tip in contact with the pubic bone.

FIGURE 7

Snap the needle guide and sling onto the sling connectors and pull through the suprapubic incision.

FIGURE 8

Perform a tension test. Remove the plastic sheaths and cut the sling flush with the skin.

Complications

Intraoperative and immediate postoperative complications include bladder perforation, vaginal or retropubic bleeding, wound or urinary tract infection (UTI), and short-term urinary retention. Possible long-term problems include urethral or vaginal erosion, mesh infection, prolonged voiding dysfunction, fistula formation, or de novo urge incontinence (TABLE 2).

Specifically, the TVT sling, which has been placed in more than 50,000 women in the U.S. and 200,000 worldwide, carries the potential for significant vascular injury and bowel perforation. In addition, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported 4 deaths (2 from unrecognized bowel injuries, 1 from retropubic bleeding in a patient with a bleeding disorder, and 1 from a heart attack more than 1 week after an incontinence repair procedure complicated by a vascular injury); 168 device malfunctions (mostly tape or sheath detachment from the trocar); and 128 other injuries, including bowel perforations and major vascular injuries to the obturator, external iliac, femoral, or inferior epigastrics (TABLE 3).8 In a review of 1,455 TVT sling cases at 38 hospitals, Kuuva and Nilsson9 found bladder perforation in 3.8% of the patients and retropubic hematoma in 1.9%, along with 1 case of vesicovaginal fistula, 1 obturator nerve injury, and 1 epigastric vessel injury.

According to the FDA, there have been 2 complications reported with the SPARC sling system. Both involved vaginal erosion subsequently repaired by oversewing the vaginal mucosa. One of these complications occurred in a woman undergoing her fourth vaginal procedure who was therefore deemed to have “poor tissue.”8

TABLE 2

Suburethral sling complications1

| COMPLICATION | 1,715 AUTOLOGOUS | 1,515 SYNTHETIC |

|---|---|---|

| Vaginal erosion | 1 (.0001%) | 10 (.007%) |

| Urethral erosion | 5 (.003%) | 27 (.02%) |

| Fistula | 6 (.003%) | 4 (.002%) |

| Wound sinus | 3 (.002%) | 11 (.007%) |

| Wound infection | 11 (.006%) | 15 (.009%) |

| Seroma | 6 (.003%) | 1 (.0007%) |

TABLE 3

TVT complications in 200,000 procedures worldwide

| COMPLICATION | U.S. | WORLD | TOTAL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vascular injury | 3 | 25 | 28 |

| Vaginal mesh exposure | 15 | 2 | 17 |

| Urethral erosion | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Bowel perforation | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Nerve injury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Outcomes studies

Unfortunately, most of the published clinical studies on the surgical management of stress urinary incontinence suffer from inadequate follow-up and sample size, unclear patient selection criteria, and poor postoperative documentation, especially with respect to quality of life. However, multiple studies to assess the effectiveness and safety of TVT slings have been published. The following is an outline of these preliminary yet important findings.

In 2002, the Cochrane Database evaluated 7 randomized and quasi-randomized trials of suburethral slings for the treatment of urinary incontinence.10 Of 682 women evaluated, 457 had some type of suburethral sling procedure. Four trials compared slings to retropubic urethropexies, 1 compared slings to Stamey needle suspensions, and 2 compared the use of different sling materials. The results indicated that the data were insufficient to suggest that slings were more effective than other incontinence procedures or that slings were associated with fewer postoperative complications. While TVT slings did provide similar cure rates as open retropubic urethropexy, research is still lacking with respect to other types of slings. More studies comparing TVT slings to traditional pubovaginal slings also are needed before the 2 can be deemed equivalent.